The US government’s comic approach to information warfare

Internet feeds swarm with cats and bots and trolls. Malicious posts, disguised on behalf of foreign agents trying to sow political and social chaos, compete for attention in comment threads, social media ads, and sophisticated Big Data-assisted influence campaigns. It can be challenging to connect with others through the noise. It can be even harder if you’re a government agency.

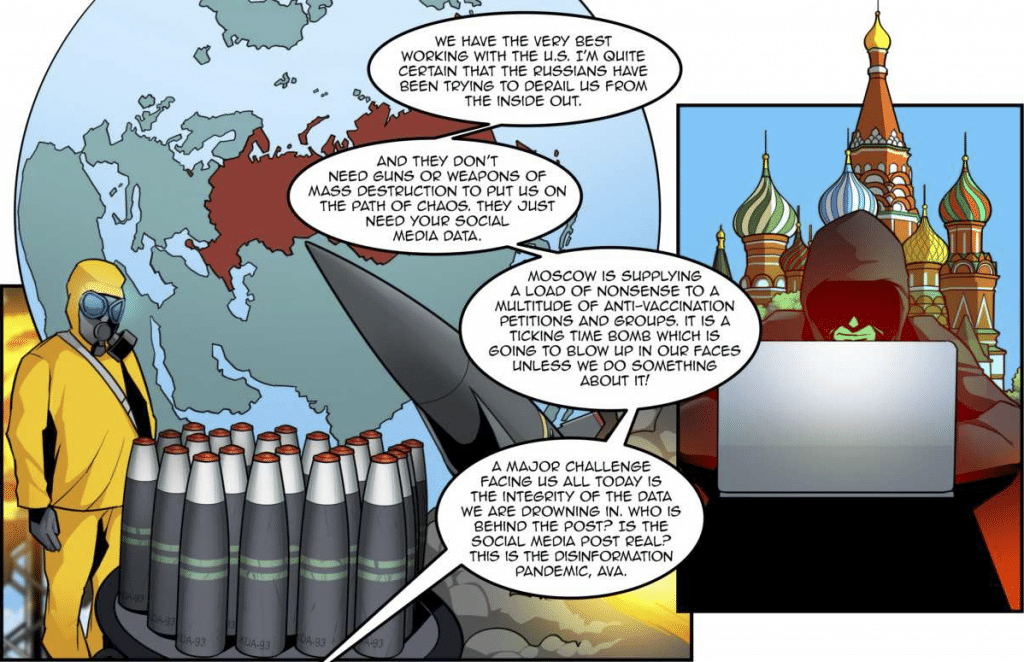

The US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency (CISA, part of the Department of Homeland Security) is trying to grapple with that dystopian information landscape as the self-styled “nation’s risk advisor.” The agency team tasked with countering mis-, dis-, and malinformation is helpfully called the Mis-, Dis-, Malinformation team (or MDM). Its mission is “to build resilience against malicious information activities,” which it labels “an existential threat to the United States, our democratic way of life, and the infrastructure on which it relies.”

With the disruptions of 2016 still echoing in the lead up to the 2020 presidential election, the agency wanted a new way to engage more people, especially young people, to arm them against disinformation: graphic novels.

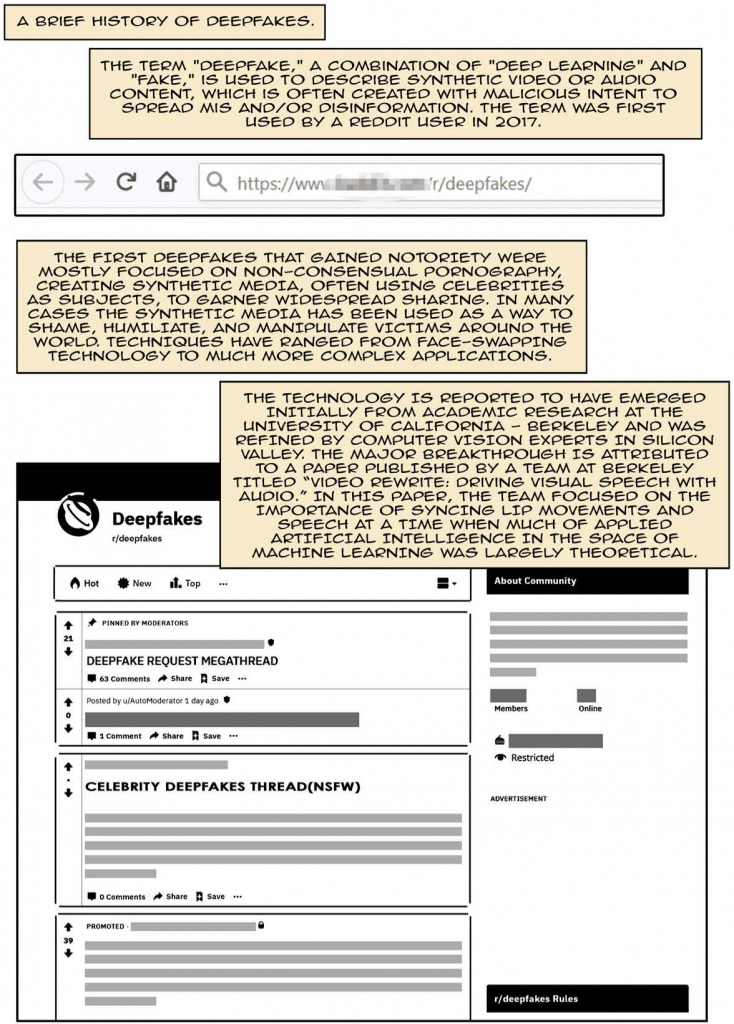

The result is CISA’s Resilience Series, “fictional stories that are inspired by real-world events.” The two titles released so far take up topics du jour like Russian troll farms, deep fake videos, and COVID-19 conspiracy theories to highlight the importance of media literacy.

Graphic novels are now a billion dollar industry in the United States. There’s certainly an audience for new visual books, including non-fiction. But is there one for government public service messages?

REAL FAKE

To find out, CISA turned to Clint Watts—a former FBI agent turned information warfare consultant who testified to Senate committees about Russia’s 2016 election interference—to write the books. A British firm, Erly Stage Studios, designed and produced them. The firm publishes graphic novels and online games with a focus on global history and social issues, including a “very graphic history” of germ warfare authored by Max Brooks for the Bipartisan Commission on Biodefense.

“We have to find new ways to engage with people through mediums that use soft power and creative messaging, rather than being seen to preach,” Erly Stage Studios CEO Farid Haque told Forbes when the first entry in the Resilience Series, Real Fake, was released. That book came out in October 2020, just before the November presidential election when fears about foreign (and domestic) disruptions of democracy were peaking.

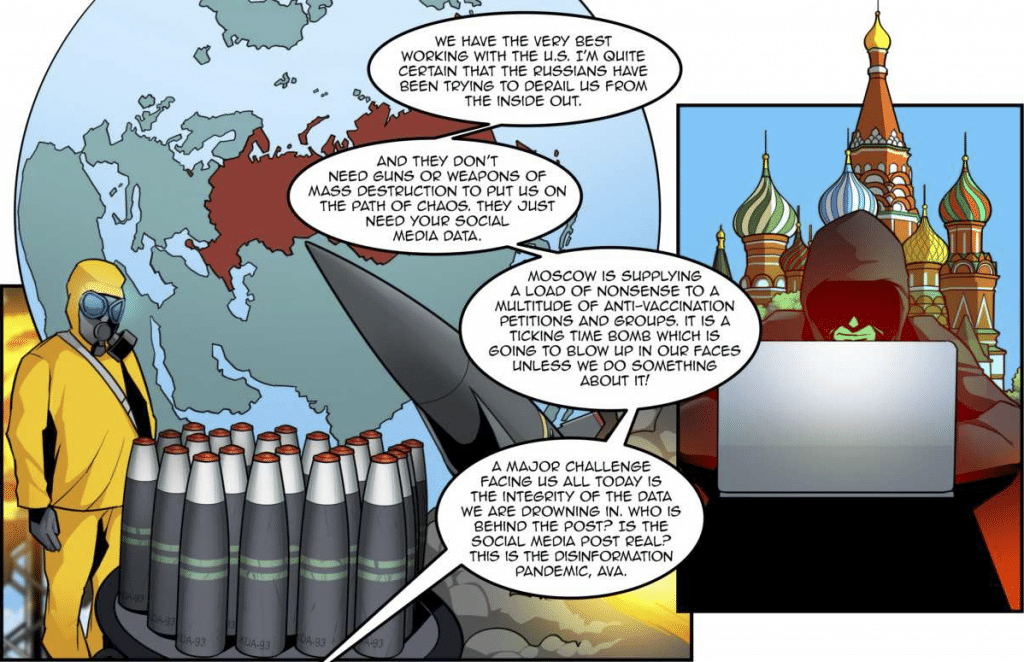

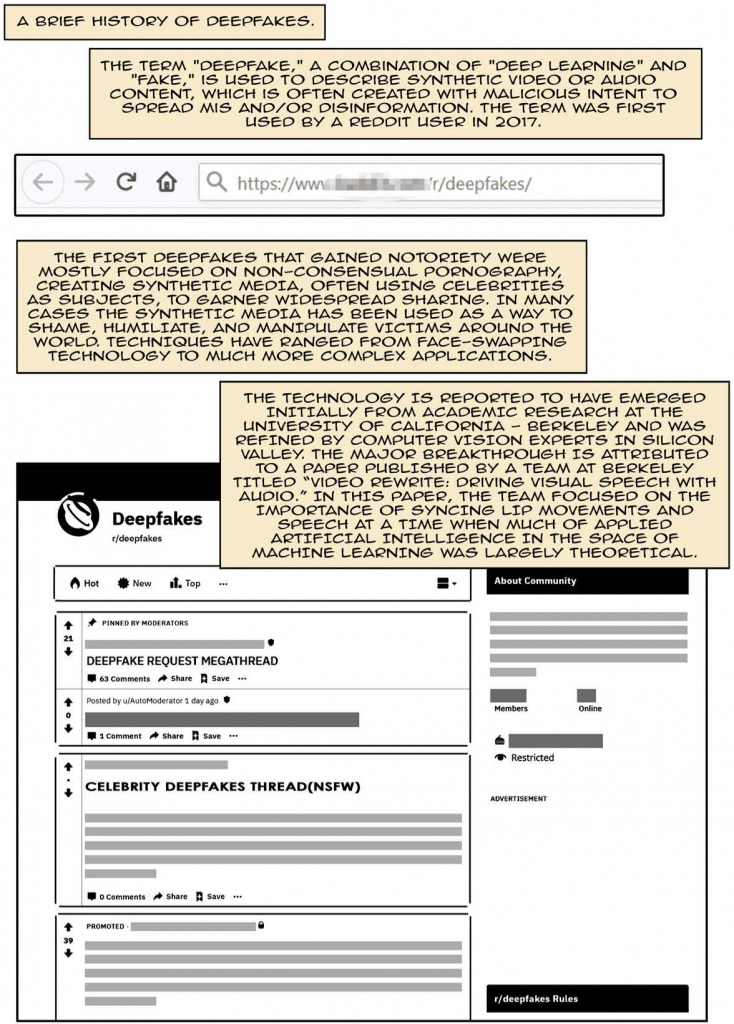

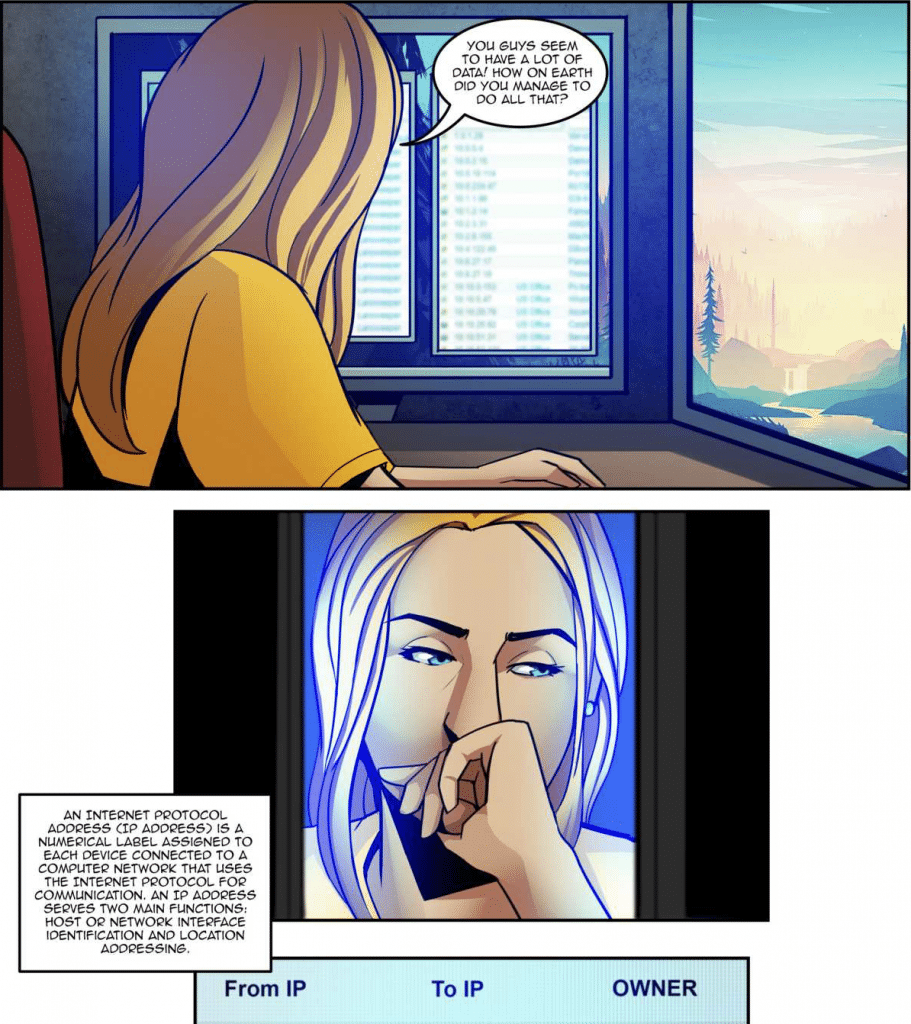

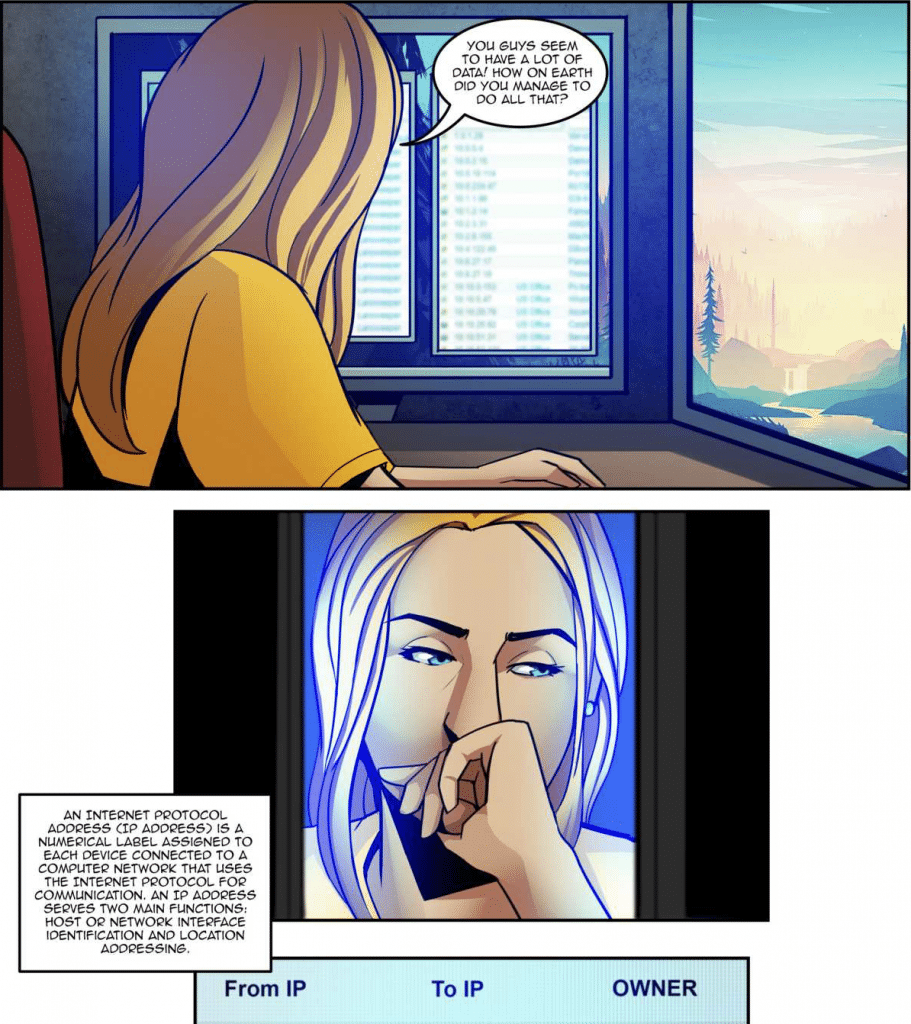

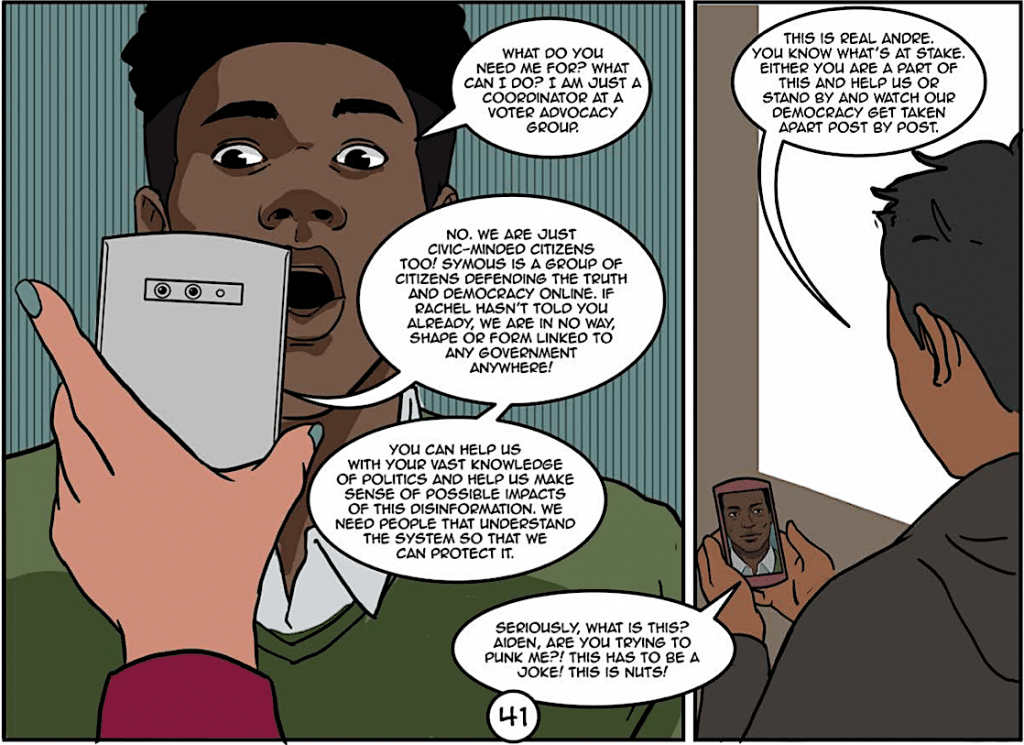

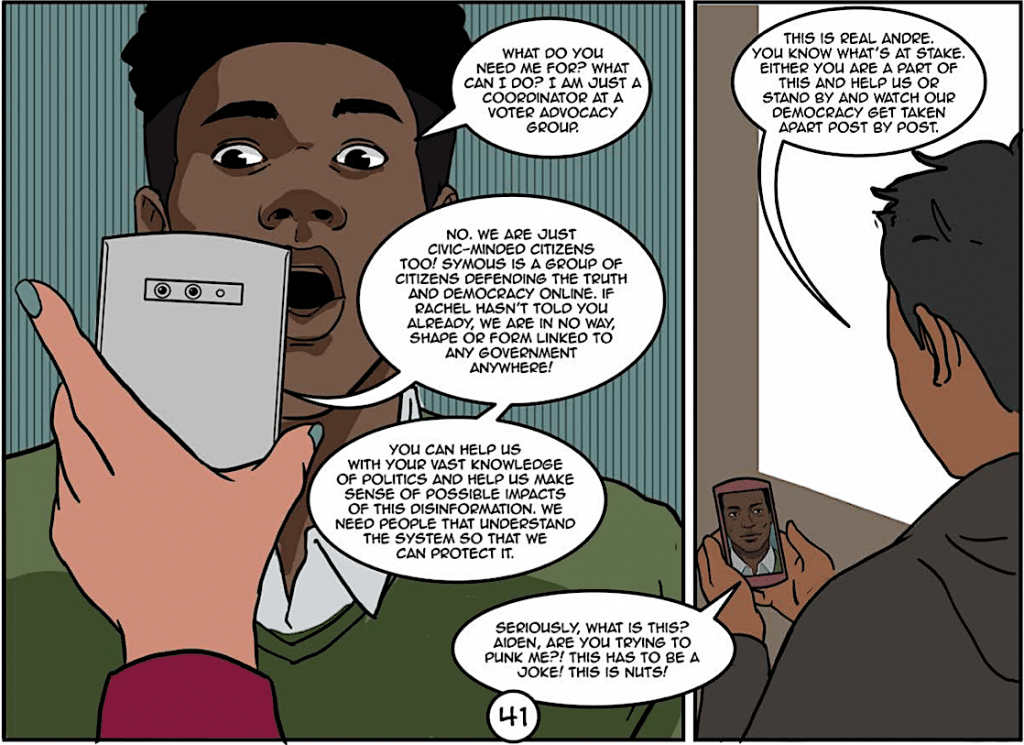

Real Fake is the story of Rachel, a “gamer, patriot” disturbed by the proliferation of deep fakes and trolls online. So she enlists some friends and her mysteriously powerful uncle, “the Chairman,” to track down their source. Real Fake is one long speech bubble detailing the complicated and decentralized global infrastructure of troll farms, spoken by the youthful protagonists and the Chairman’s secretive justice-seeking outfit called Symous. That sounds like it could be a fun comic with informative accounts of real-world threats weaved in, but it never really gets there. Real Fake serves up a lot of dense information (including a 10-page primer on deep fakes and a bibliography) at the expense of character development and visual thrills. The pacing often feels uneven and rushed, jumping from one idea or location just as it is beginning to be explored, with few visual cues to help the reader along.

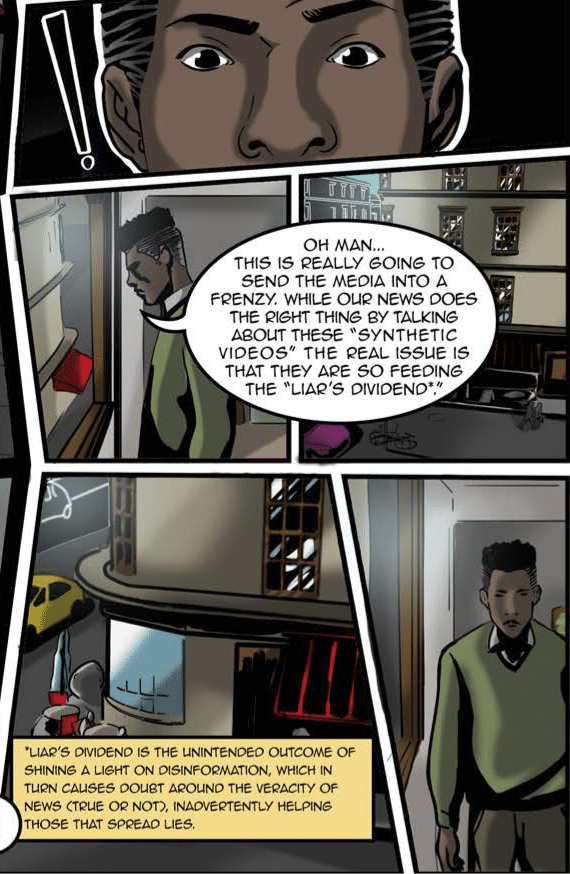

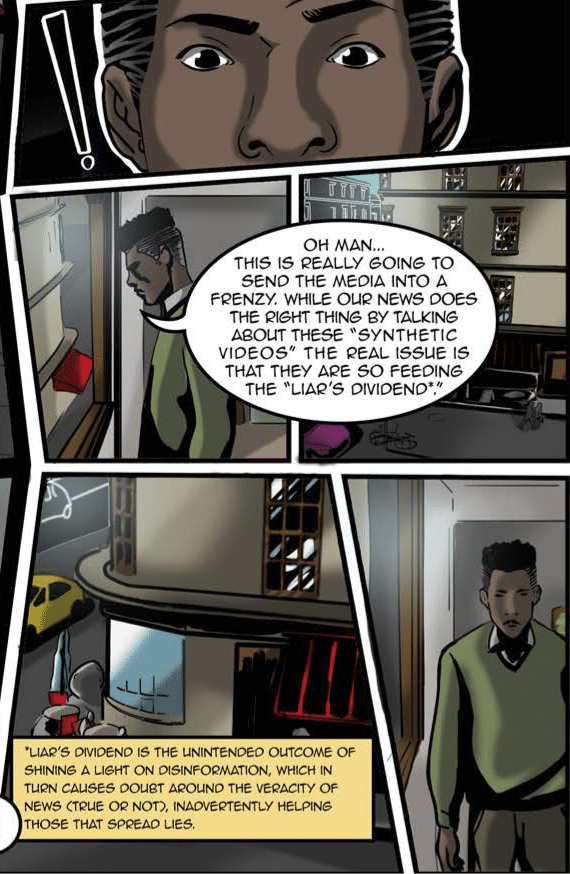

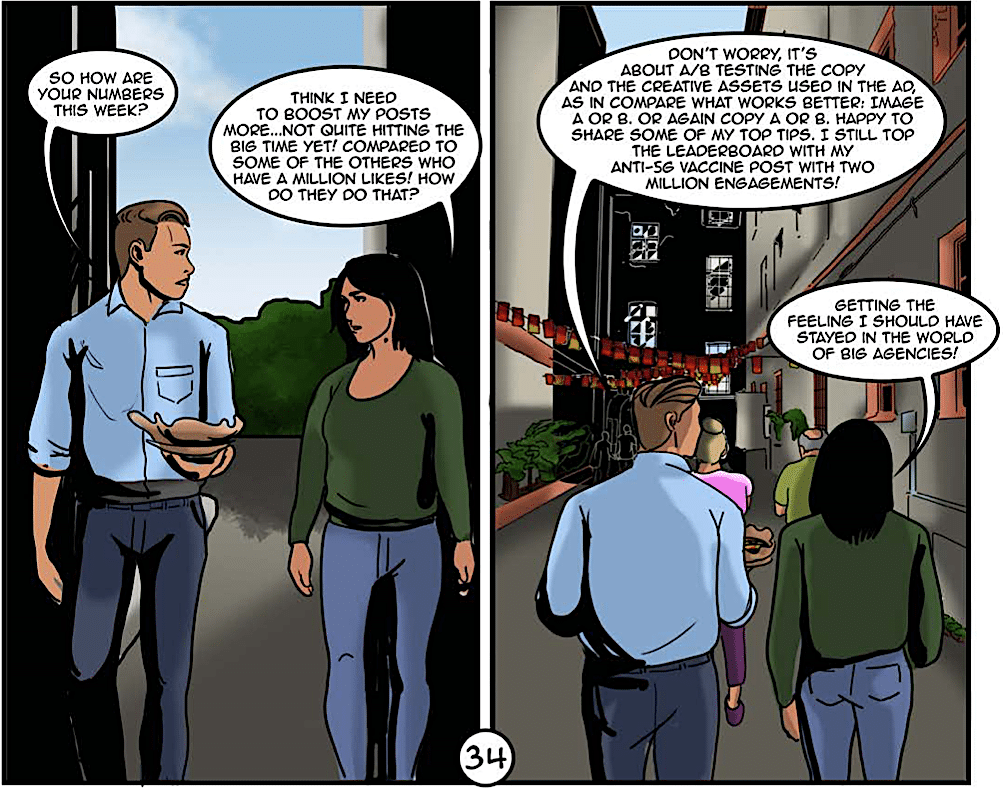

There are other missed opportunities to embrace the hero genre and the graphic novel format itself. Take this intriguing panel, in which self-described journalists at a “Western Europe” troll farm naively discuss how best to promote a deep fake video they evidently think is real:

What’s intriguing is why the authors chose to write an aside about A/B tests (perhaps meant to show the banality of evil?) rather than actually depict sample disinformation posts, with all the color afforded by the medium. There are, in fact, very few examples in Real Fake of the actual content CISA is trying to warn readers about. Many of the panels consist of people sitting or standing around tables and planes explaining general concepts (or the plot) to each other. The story throws a lot of ideas at the reader, with the confusing takeaway that misinformation is a very complex problem that anyone empowered by media literacy can thwart … but maybe only if you can also fly on a private jet to Moscow and infiltrate an active troll farm operation.

BUG BYTES

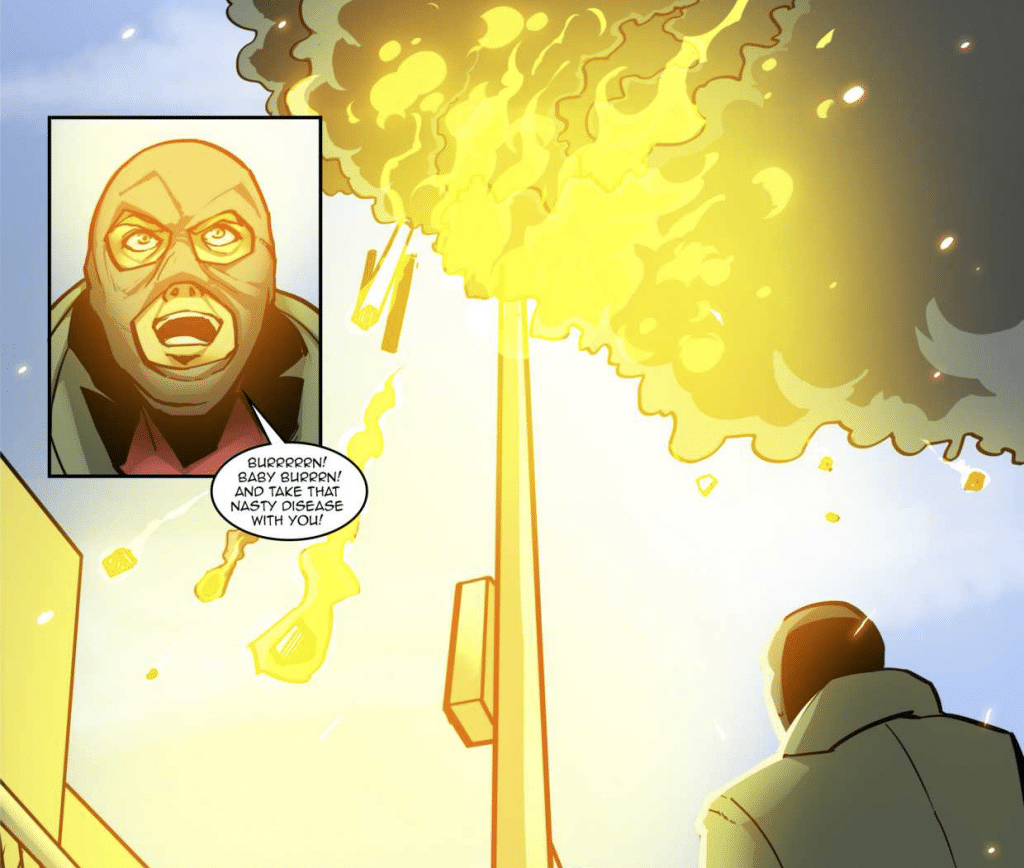

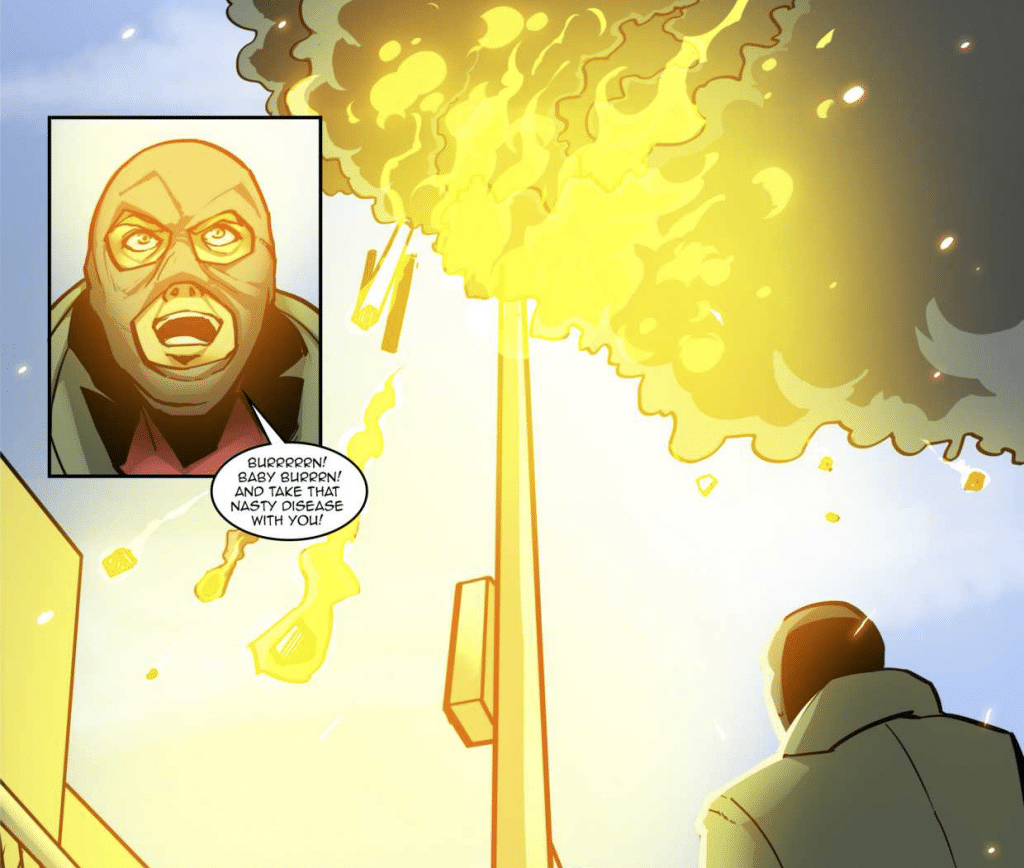

The authors made some welcome adjustments with the second issue in the series, Bug Bytes. Released in April this year, it adds a lot more excitement and character to a more coherent and (somewhat) believable narrative. This time our hero, Ava, is a journalism student. A few pages in, Ava’s father, a cell-tower technician, is beaten by crazed anti-5G hoodlums. While her father recovers, Ava goes on a quest to understand the attack, leading to some dramatic encounters and a lot of tutelage.

Conspiracy theories about the health impacts of 5G towers and their connection to COVID-19 and vaccines have led to real-world assaults, along with the burning of 5G towers, particularly in the UK. (For more coverage of COVID-19 conspiracy theories, check out the Bulletin’s Infodemic Monitor series.)

“This seems like the result of a malicious cyber campaign!” Ava swiftly deduces about the fictional attacks in Bug Bytes, before stumbling into the orbit of Symous, the same shadowy and well-funded cyber-intelligence group that underwrites the action in Real Fake.

From there the story gradually picks up steam into another tale of citizens qua vigilantes, though with significantly improved use of of the graphic format. Unfortunately, the unlikely heroics of the protagonists still muddles the message—this time, when you reach the end of Bug Bytes, you find out the real champion is … wait for it … independent journalism. As a journalist, I confess to appreciating the flattery contained in that storyline, which clearly emphasizes the value of vigilance about facts. But who are these graphic novelettes for, really?

CIVIL DEFENSE IS CANON

CISA’s graphic novels aren’t the first time in recent memory that government agencies have used comics to combat threats. A decade ago, the CDC went all in with a zombie apocalypse comic to encourage emergency preparedness. And in 2018, the US Army Cyber Institute worked with researchers at Arizona State’s Threatcasting Lab on a set of graphic novels to help West Point cadets learn about 21st-century dangers like drones and hackers. (CISA itself previously tried other fictional methods to raise awareness of information threats, like its 2019 infographic and social media campaign detailing foreign interference in the “War on Pineapple.” At the time the agency said it had “no evidence of Russia (or any nation) actively carrying out information operations against pizza toppings.”)

CISA’s Resilience Series is unusual, though, in that it seems to put the onus on individuals—“just civic-minded citizens”—to confront the danger of mis-, dis-, and malinformation. Perhaps unexpectedly for a publication coming out of the Department of Homeland Security, the running thread in both books ends up being about the triumph of non-government actors (albeit with resources comparable to those of Marvel’s S.H.I.E.L.D.).

In fact, the responsibility of powerful governments or corporations in both stories seems peripheral at best, and in some cases even presented as morally ambiguous (like when a hapless employee at a social media content farm in “West Africa” is thrown in jail for writing stories on assignment).

These are not disguised brochures for CISA. The overall message of vigilance is an important one, even if it sometimes functions like poorly hidden vegetables in a toddler’s mac and cheese.

But the Resilience Series still conjures a certain jingoism peculiar to government publications that can mimic the very threat being addressed. “You cannot use scientific rationality and numbers to win this war,” a media studies professor tells Ava in one of the many didactic moments in Bug Bytes. “You need to win their hearts and minds first and then show them the truth!” It takes 49 pages of instruction with pictures to get to “hearts and minds,” but it gets there.