Officials say an elections supervisor who embraced conspiracy theories has become an insider threat

In April, employees in the office that runs elections in western Colorado’s Mesa County received an unusual calendar invitation for an after-hours work event, a gathering at a hotel in Grand Junction. “Expectations are that all will be at the Doubletree by 5:30,” said the invite sent by a deputy to Tina Peters, the county’s chief elections official.

Speaking at the DoubleTree was Douglas Frank, a physics teacher and scientist who was rapidly becoming famous among election deniers for claiming to have discovered secret algorithms used to rig the 2020 contest against Donald Trump. Frank led the crowd in a rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” and spent the next 90 minutes alleging an elaborate conspiracy involving inflated voter rolls, fraudulent ballots and a “sixth-order polynomial,” video of the event shows. He was working for MyPillow chief executive Mike Lindell, he said, and their efforts could overturn President Joe Biden’s victory.

Being told to sit through a presentation of wild, debunked claims was “a huge slap in the face,” one Mesa County elections-division employee said of the previously unreported episode. “We put so much time and effort into making sure that everything’s done accurately,” the employee told The Washington Post, speaking on the condition of anonymity out of fear of retaliation. Peters, the elected county clerk, had expressed sympathy for such theories in the past, the employee said.

Over the course of the past month, in a lawsuit filed by the state’s top elections official, Peters and her deputy have been accused of sneaking someone into the county elections offices to copy the hard drives of Dominion Voting Systems machines. Those copies later surfaced online and in the hands of election deniers. The local district attorney, state prosecutors and the FBI are investigating whether criminal charges are warranted.

The events in Mesa County represent an escalation in the attacks on the nation’s voting system, one in which officials who were responsible for election security allegedly took actions that undermined that security in the name of protecting it. As baseless claims about election fraud are embraced by broad swaths of the Republican Party, experts fear that people who embrace those claims could be elected or appointed to offices where they oversee voting, potentially posing new security risks.

“I’ve always worried, working in this space, about people who want to harm our elections or sabotage them from the outside – the foreign actors trying to hack elections,” said Mike Beasley, a lobbyist for the Colorado County Clerks Association. “I’ve never until now had to worry about what goes on on the inside. And now we’ve crossed that threshold.”

Trump in recent months has endorsed several proponents of the “big lie” to become secretaries of state in key battlegrounds. And experienced election administrators at the local level have been fleeing their jobs amid skyrocketing stress and threats to their personal safety.

“If these local offices become weaponized in a way that subverts the free and fair election, then we no longer live in a healthy democracy,” said Tammy Patrick, an election-administration expert and senior adviser to the Democracy Fund, a nonpartisan private foundation that seeks to strengthen voting systems.

The lawsuit was filed by Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold, a Democrat whose office supervises elections run by county clerks. It seeks to strip Peters and her deputy, Belinda Knisley, of their election powers, arguing that they were responsible for an “unprecedented security breach.” For that reason, Griswold argues, Peters cannot be permitted to have access to county voting equipment.

Griswold alleges that an unauthorized person was given a key card and that Peters’s office falsely claimed that that person was a county employee. Security cameras in the elections offices were turned off, Griswold alleges, before Peters and the unauthorized person swiped in on May 23 – a Sunday, the day the hard drive was copied for the first time.

After those events became the subject of an investigation, Peters stopped going to her office, saying she feared for her safety. From an undisclosed location, she urged one of her employees in an email not to speak with investigators – and to spread that message to other employees, according to the email, which was among numerous documents The Post obtained for this story through public records requests.

Neither Peters nor Knisley agreed to be interviewed for this story, and neither answered questions sent by email. Their lawyers have argued that at worst the two women committed “several technical violations of election regulations, none of which justify removal of an elected official.” They have said that the two were within their rights to bring in a consultant, and that Peters and Knisley never authorized confidential data to be published online.

Speaking last week on a podcast aimed at conservative Christians, Peters acknowledged that she “commissioned somebody to come in” to copy the hard drives. The idea was to make one copy before a planned software update and another copy after, she said, and then to compare them to determine whether files necessary to investigate past elections were deleted.

Peters insisted her actions were necessary to protect election security – and she called on county clerks elsewhere to follow her lead and copy their own voting-machine hard drives. She alleged that she has become the target of powerful forces that do not want her to get to the truth.

“They will stop at nothing to shut this up,” she said. “I’m willing to go as far as it takes to do what needs to happen. I mean, God’s called me, He’ll sustain me and He’s surrounding me with His people. So, I feel very good.”

Lindell told The Post that in recent weeks he has paid for Peters’s lodging, security and lawyers. He hopes that other elections officials will come forward to join the fight.

“We want to get more Tinas,” Lindell said recently on his twice-daily online show. “We need more Tinas out there.”

A shift in tone

Peters, who is in her mid-60s, spent years running a family construction company and at one point sold magnets and other alternative wellness products through Nikken, a multilevel marketing firm, according to her YouTube channel and an archived version of her website. In 2017, she decided to run for clerk in Mesa County, a Republican stronghold on Colorado’s Western Slope.

Peters campaigned during the 2018 primary on a promise of shorter lines at the motor vehicle department. She beat her opponent, a longtime employee of the clerk’s office, and was not opposed in the general election.

But the following year, Peters’s office – beset by staff turnover – failed to collect and count 574 ballots that had been left in a drop box during a November 2019 election. Residents mounted an unsuccessful recall effort, the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel’s editorial board called for her resignation, and the secretary of state sent a monitor, former Eagle County clerk Teak Simonton, to oversee the county’s administration of a primary in the summer of 2020.

In a report to the secretary of state, Simonton wrote that Peters had been “distrusting, frequently rude and antagonistic,” but that her staff was cooperative, hard-working and committed to integrity.

Simonton told The Post that while she found Peters to be difficult to work with, “there was nothing that I saw that gave me an impression that the election was being run illegally or unethically or with a slant toward certain candidates and not others.”

After the 2020 presidential election, Peters initially declared that she was proud of the smooth, secure election her office had run. But her tone shifted as Trump and his GOP allies repeated baseless claims of fraud.

On Jan. 2, Sen. Patrick Toomey, R-Pa., published a series of tweets affirming Biden’s victory and criticizing his Republican colleagues who planned to challenge it on Jan. 6. “UR Dirty or ignorant,” Peters tweeted in response, the Daily Sentinel reported at the time. “You would be wise to learn the Constitution that you swore to uphold and to protect us from enemies ‘foreign and domestic.’ “

In early April, Grand Junction held a municipal election for four nonpartisan city council seats. The winners did not include any of the candidates endorsed by Stand for the Constitution, a far-right group that has unsuccessfully urged county officials to declare the county a “constitutional sanctuary” where federal laws do not apply. The outcome stoked suspicion in some quarters that the election results could not be trusted.

“When I started having citizens come to me and tell me that something didn’t seem right … I said you know what? If there’s a ‘there’ there, we’ll find it,” Peters later recalled at a symposium Lindell organized to push election-fraud claims.

Seventeen days after the Grand Junction City Council election, Douglas Frank came to town. At the DoubleTree event, he said that Lindell had paid for his trip.

In an interview, Frank said that before his public talk, he met privately with Peters and members of her staff – one of a hundred meetings he estimated he has held in recent months with election administrators across the country. He said he told Peters that voter rolls in Mesa County included people who had died or moved elsewhere, and that fraudulent ballots have been cast in those people’s names, a claim for which no evidence has been offered publicly.

“I sat down with her and showed her how her election was hacked, and she brought in all of her employees, one after the other,” he said.

Frank said he spoke to Peters about an upcoming Dominion software update that he believed could delete the data they needed to prove the election had been rigged. He said he told her that she had a responsibility under federal law to preserve election records, including data from the machines.

“She said ‘Well, how do I do that?’ ” Frank recalled. “I said, ‘I’ll put you in touch with people who can help you.’ “

He said he relayed her request for aid to someone in Lindell’s circle.

Key cards retrace steps

Because voting machines are not connected to the internet, their software must be updated manually, a tightly controlled process called a “trusted build.” In Colorado those updates require passwords set by officials at the Colorado Department of State, the agency led by Griswold. Mesa County was scheduled to undergo its trusted build on May 25.

Peters wanted to let members of the public observe, but state officials denied that request, citing concerns about security and covid-19, emails show. The only people who could attend were authorized county election staff and officials from the department of state and from Dominion, a favorite target of election deniers.

On May 14, emails obtained by The Post show, Knisley requested that a county email address be created for a “Gerald Wood,” a person she described to county IT staff as a “temp person for the Elections Department.” She indicated that he should receive the same computer permissions as Sandra Brown, a manager in the elections division.

On May 18, a week before the trusted build, Brown told her contact in the state department that she would be one of the county staffers to attend the trusted build and that Wood would be the other. She listed his position as “administrative assistant,” according to an email obtained by The Post.

According to county officials, no one by that name was actually hired as an employee or contractor. Brown did not respond to voice-mail messages. County officials have suspended her with pay pending the outcome of the investigations.

At some point before the trusted build, security cameras were turned off, an action that was “outside of the normal business practice of Mesa County,” according to Griswold’s lawsuit. Documents obtained by The Post show that the director of the elections division asked the IT help desk in early June why the cameras were not working properly. She was told that Knisley had requested that the cameras be turned off until the end of July, the documents show.

Lawyers for Peters and Knisley have not disputed that the cameras were turned off but have said turning them off during that period was permitted under state election rules.

On Sunday May 23, the day Griswold says the hard drive was first copied, key cards assigned to Peters, Brown and Wood were swiped to enter the election division area of the clerk’s office, according to security logs. Each card was used to access that area multiple times, with the first swipe just before 11 a.m. and the last at 8:38 p.m., the logs show.

Two days later, officials from Dominion and the state department visited Mesa County for the trusted build. Brown and Peters were there, security logs show, as was the person known as Gerald Wood. In a filing as part of the lawsuit, Griswold alleged that Peters falsely told state officials that Wood was a staffer transitioning to elections from the motor vehicles division.

During the trusted build, someone made a video recording and still photos, Griswold’s lawyers later asserted in a court filing. Lawyers for Peters wrote that while she took a video and photographs, she never authorized any imagery from the trusted build to be posted online.

On May 26, another copy of the Dominion hard drive was made, according to a consultant’s report filed in court by Peters’s and Knisley’s attorneys. Security logs show that key cards belonging to Peters, Brown and other county employees were used to access the elections room on that day. The card belonging to Wood was not.

In the weeks that followed, election deniers in Colorado began spreading the idea that Dominion and the secretary of state were wiping out data that was necessary to prove that prior elections had been fraudulent.

“Right now these people who’ve done this are covering their tracks, and they’re doing it in a very quick manner,” Sherronna Bishop, a Peters ally, told fellow activists during a June video conference call in which they discussed pressuring county clerks across the state to delay their software updates. The Post obtained a recording of the call.

In response to a request for an interview, Bishop, a former campaign manager for Rep. Lauren Boebert, R-Colo., asked for a list of questions to which she then did not respond.

A Gerald Wood who lives near Grand Junction also did not respond to several messages left on his home phone. Investigators have not disclosed if they believe Wood is the person who accessed the elections offices. His Facebook account shows he has liked one page: Bishop’s.

Peters’s profile rises

The first public inkling that someone had leaked information from inside the Mesa County elections office came on Aug. 2. Ron Watkins, the former administrator of the 8kun message board where the QAnon conspiracy theory has been promoted, began to publish photographs of election equipment, images he said he had obtained from a whistleblower. He called the person who provided the images a “hero” who “went to excruciating effort to detail and archive everything possible.”

Some of the photographs showed pages from a manual for upgrading Dominion machines, while others showed images of Dominion server screens. Watkins warned that he had to redact the images carefully, as a “minor slip-up could potentially dox the whistleblower.”

Watkins wasn’t careful enough. An image he posted showed a spreadsheet of sensitive passwords used to access various Dominion computers and servers. The passwords had been set by state officials, and they were unique to machines in Mesa County.

A week later, the two hard-drive copies appeared online.

The impact of the leak on the wider election-security landscape is a matter of debate. Some experts said hackers could use the leaked material to try to find vulnerabilities in widely used Dominion machines, while others said malicious actors probably already know how voting-machine software works. Either way, Colorado, like many states, uses paper ballots that can be counted to make sure that machine tabulations are accurate.

Inside the county, the impact of the leak quickly became clear. On Aug. 9, Griswold demanded that state officials be permitted to inspect Mesa County’s equipment. Three days later, she ordered the decertification of 41 pieces of equipment. Five days after that, citing the breach, she appointed a supervisor to oversee the county’s elections, and she barred Knisley and Brown from any involvement in county elections work.

During that same period, Peters was becoming a minor celebrity among election deniers. On Aug. 10, according to an email Peters wrote, Lindell had sent his private plane to pick her up in Colorado and take her to the symposium starting that day in South Dakota.

Lindell billed the 72-hour symposium as the venue where he would finally reveal detailed cyber evidence to back up the claims he had been making for months about the 2020 election.

No such evidence was presented, according to independent security experts who attended the symposium. But the event served as a coming-out party of sorts for Peters, who was cheered as a hero when she appeared onstage the first night. She claimed that the secretary of state, who had sent civil servants to inspect Mesa’s equipment earlier in the day, had “raided” her office.

“In Colorado, we know we are a red state. We know we are,” said Bishop, speaking alongside Peters. “We have 64 counties in Colorado, and we have one clerk who would stand up for us and fully investigate.”

The following day at the symposium, discussion of the two Dominion hard drives from Mesa County was briefly interrupted by Watkins, who said his lawyer had advised them to stop talking because the hard drives may have been stolen from Mesa County. With the event streaming online, Watkins said his lawyer, Ty Clevenger, said they may have been stolen by Conan James Hayes – a former pro surfer who started working for Lindell earlier this year, Lindell told The Post.

Peters immediately took to the stage to deny that. “There was nothing, no hard drives that belong to our equipment that were taken off the premises,” she said, “unless it happened during the raid.”

A few moments later, Watkins again interrupted. He had more news. Clevenger had just told him that Hayes “did have permission to take the hard drive, but did not have permission to upload it.” Clevenger had heard this update from Bishop, Watkins said.

Clevenger told the news outlet Vice that Hayes was Watkins’s source for the hard drives. In an interview with The Post, Clevenger said he was no longer commenting on the matter publicly.

The drives’ metadata show that the copies were created by a computer using the initials “cjh,” two cybersecurity specialists who reviewed the hard-drive copies told The Post. Lindell told The Post he did not know anything about whether Hayes was involved in copying Mesa County’s hard drives.

Attempts to reach Hayes were unsuccessful. Lindell said he would pass on a reporter’s interview request to Hayes but warned that Hayes was unlikely to speak to The Post.

As Peters’s national profile was rising in South Dakota, officials at home were obtaining search warrants to examine her cellphone data, take DNA swabs from election machines, remove Dominion equipment from Mesa County’s offices and obtain records to determine who had had access to the secure tabulation room since Frank’s visit in April, according to copies of the warrants reviewed by The Post.

The U.S. Election Integrity Plan, a group that has served as a key engine for election-fraud claims in Colorado, posted online copies of what it said were court documents related to the investigation. The records detailed a search during that same period of the home near Grand Junction where Gerald Wood lives. Investigators seized cellphones and other electronics, according to the document.

In a statement to The Post, the district attorney’s office said: “We suspect the document you saw online is of the search warrant inventory but cannot confirm its authenticity as the case is sealed.”

On Aug. 23, county officials suspended Knisley with pay after multiple complaints that she engaged in “inappropriate, unprofessional conduct in workplace behavior,” according to documents filed in court. She was ordered to stay away from her office, and her access to the county’s email and computer systems was disabled, documents show.

But two days later she was found in the clerk’s office, where someone had used Peters’s credentials to log in to her computer and tried to print documents, according to an affidavit from an investigator with the district attorney’s office. Knisley was later charged with felony burglary and a misdemeanor cybercrime offense.

On Aug. 27, an employee in the clerk’s office told Peters via email that she had been advised to alert the county’s human resources department if Knisley showed up again. She asked Peters whether she should pass that guidance along to the rest of the staff. Peters advised her to “hold off” on spreading that message – and to instead spread another.

“No one has any obligation to speak to any law enforcement and are encouraged not to do so,” Peters wrote. “They need to refer all to me and I will have our attorney be in touch with them.”

By then, Peters had not been in her office or appeared publicly in Grand Junction for more than two weeks. In one email to a local television reporter, she claimed she had been advised to work remotely because of threats to her safety.

In an exchange with the county attorney, Peters wrote about her concerns that her computer had been removed from her office. The county attorney responded that he was surprised to hear from her given her long absence.

“You assume too much,” she replied. “I am closer than you think.”

Peters’s profile rises

On Sept. 16, Peters made a triumphant return home at a rally organized by Stand for the Constitution, the group that has sought to have Mesa County declared a “constitutional sanctuary.”

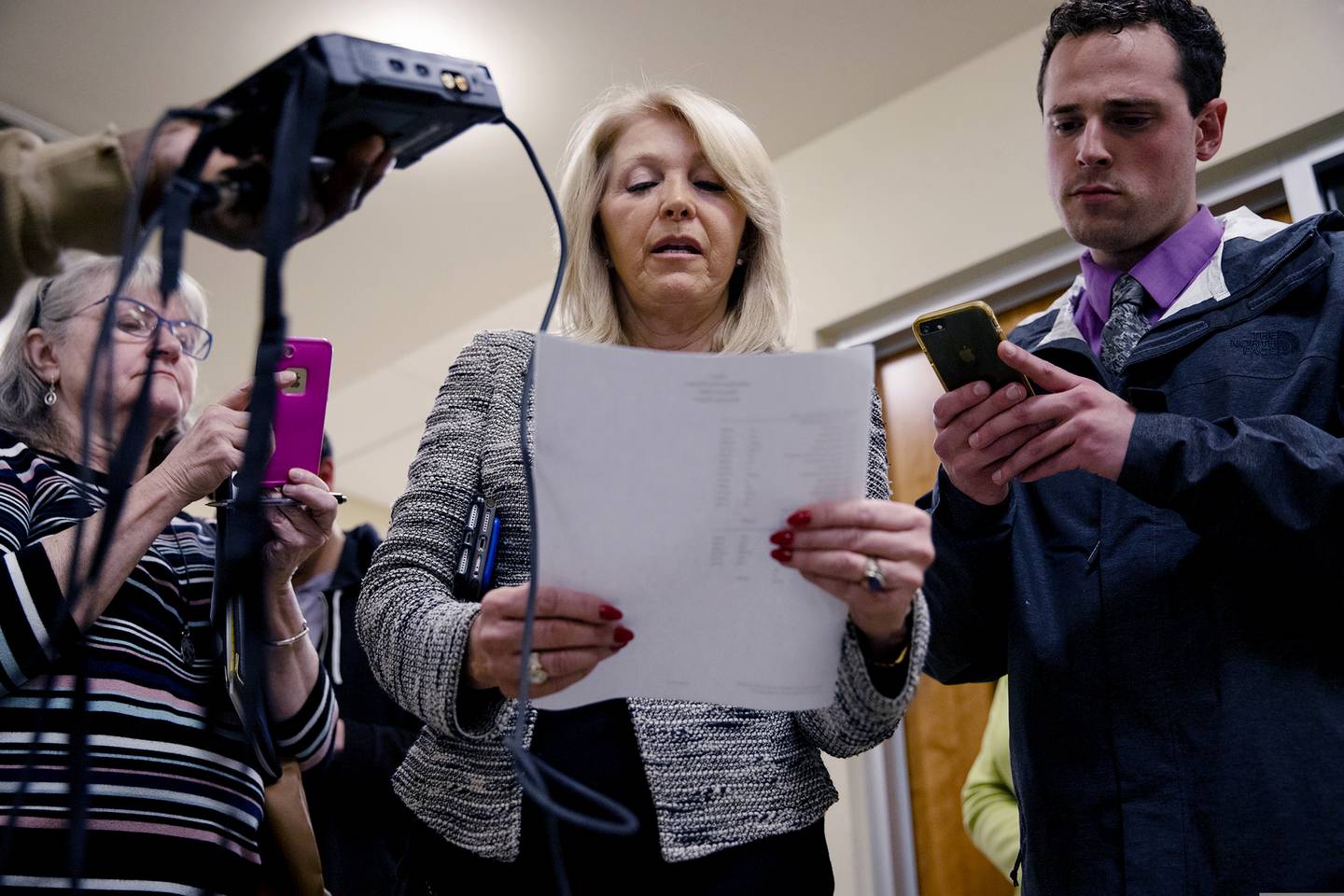

After 38 days away, Peters arrived at a Grand Junction church in a black Suburban with dark tinted windows. She slipped in the church’s side door and stood before a large wooden cross as about 250 maskless rallygoers jumped to their feet, clapped, waved and cheered wildly.

“This is all for you,” she said, breaking into tears. “You’re the ones who came to me and said ‘something’s not right.’ “

The next day, lawyers representing Peters and Knisley countersued Griswold. They filed in court a report by their own cybersecurity consultant. It claimed the copied hard drives showed that during the trusted build, election records had been “DESTROYED IN VIOLATION OF THE LAW.”

“There is nothing further from the truth,” lawyers for Griswold’s office wrote in their response. Some files were deleted during the trusted build, as would be expected during such an update, but they were not election records and were not required to be preserved, they wrote. Griswold’s office had explicitly instructed officials in Mesa County and across the state to back up their elections files prior to the trusted build so those files wouldn’t be lost, emails show.

The county’s next election will be in November. Ballots will be cast on Dominion machines. Mesa County’s three commissioners, all Republicans, recently voted to extend their contract with Dominion through 2029, saying they had seen no evidence of fraud.

Still, the ballots will be electronically tabulated twice, once on Dominion machines and once on machines made by another company, ClearBallot. They also will be hand-counted. Finally, images of the ballots will be posted online for all to see. Those steps were necessary to reassure voters, the commissioners decided, because of the suspicions roiling Mesa County.

The Washington Post’s Jon Swaine, Magda Jean-Louis and Jennifer Jenkins in Washington and Nancy Lofholm in Grand Junction, Colo., contributed to this report.