Far-right Covid conspiracy theories fuelling antisemitism, warn UK experts

A surge in Covid-19 conspiracy theories risks boosting antisemitism, hate crime campaigners have warned after the opening of an exhibition shedding light on interwar British fascism and its parallels today.

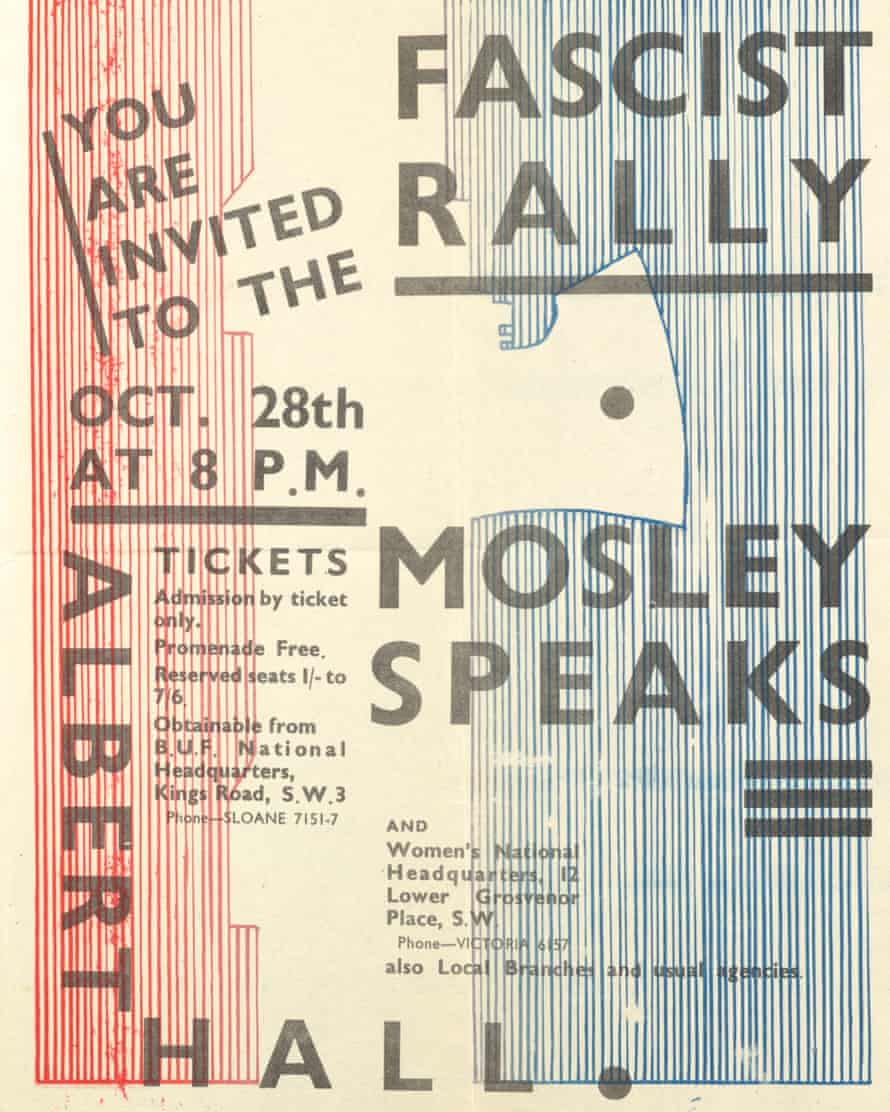

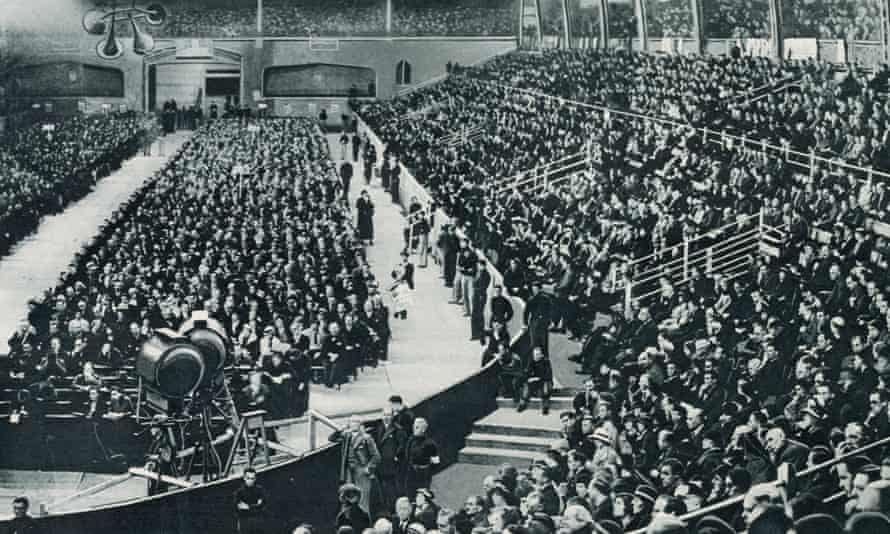

The Wiener Holocaust Library in London is staging the exhibition – focusing on the motivations and propaganda of British fascists and their European peers in the 1920s and 30s – out of concern about the recent growth of far-right ideas and populism in the UK and abroad.

Rare photographs including one of a woman on the streets of London wielding a union flag with a swastika at its heart are featured in the exhibition.

“We want – want quite consciously – to get people thinking about the parallels between the past and the present, as well as the differences,” said Dr Barbara Warnock, co-curator of the exhibition.

She said a copy of Action, the newspaper of Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists (BUF), carrying the headline The Return of Manhood, had similarities to the misogyny increasingly weaponised by the far right today. The newspaper’s front page also carries the Britain First motto – a fascist slogan that is also the name of a far-right group that last month had its application to register as political party approved by the Electoral Commission.

Parallels can also be drawn between antisemitic conspiracy theories about Covid-19 and the development of vaccines, and pamphlets blaming “Jewish financiers” for the first world war or suggesting they would gain from the second world war.

David Rich, the director of policy at the Community Security Trust (CST), a charity providing security for the Jewish community, said the pandemic had resulted in people with antisemitic views taking central roles in the campaign against Covid vaccines and public health measures.

“We’ve increasingly been seeing people not really attached to one particular ideology but who are part of this amorphous mass fuelled by conspiracy theories. An entry point to that has come with the pandemic and the anti-vaccination movement where the language is not explicitly anti-Jewish. It means that a lot of people are at risk of getting sucked in,” said Rich, who will be among speakers at events taking place as part of the exhibition.

Others will include Joe Mulhall, the head of research at Hope not Hate , who said the anti-racism group was concerned that individuals had become radicalised inside organisations that were now getting smaller but more extreme as the pandemic waned and would become more fixated on antisemitic beliefs.

“There is an unbroken lineage within the British far right which goes all the way back to the 20s and 30s, which is explored in this exhibition. In some ways those prejudices and hatreds have remained unchanged, but what has evolved is the way they’re distributed, and that’s the internet,” he said.

“Electorally, the far right has collapsed since 2010 and there’s now a very splintered scene all over the country, but a lot of their politics has become normalised and part of the mainstream.”

The exhibition, This Fascist Life: Radical Right Movements in Interwar Europe, draws on items from the library’s own archives and the Searchlight Archives at the University of Northampton.