It’s Not Q. It’s You

Truth be told, we are a nation of spectacular liars. We lie to ourselves about our origin, our exceptionality, that our wealth and power stems from that exceptionality rather than from economic systems of exploitation. Lies are embedded in our founding and our growth and probably our eventual doom. Spurred on by Sam Adams, a riotous mob stormed the Massachusetts governor’s mansion because they believed outlandish theories about how he was conspiring with the Brits. Spurred on by Trump, a riotous mob stormed the Capitol because they believed outlandish theories about how Nancy Pelosi was conspiring with Joe Biden. Or Mike Pence. Or Satanic deep state baby eaters. Or whatever the hell.

Not all lies are conspiracy theories, but probably most conspiracy theories are lies. And according to Joseph Uscinski, arguably the country’s foremost expert on the topic, it’s possible we’re even lying to ourselves about the nature of conspiracy theories.

As a professor of political science specializing in public opinion and mass media at the University of Miami, co-author of American Conspiracy Theories, and editor of Conspiracy Theories and the People Who Believe Them, Uscinski spends a great deal of time pondering the untrue beliefs of others. With careful data, polling, and research, he has been tracking dozens of conspiracy theories — and the general mindset that drives them — for over a decade. He’s the guy every expert you talk to says you need to talk to. And when I reached out to him wanting to understand the psychological effects of a conspiracy theory like QAnon, he kindly let me know that I was probably getting it all wrong.

As Uscinski explains it, conspiracy theories don’t affect people so much as people affect them. And those people aren’t unwittingly sucked by powerful algorithms down a rabbit hole of dis- and misinformation but rather are drawn there by what they already believe — or want to believe — is true. “This discussion is often framed backwards,” Uscinski tells me. “It suggests that internet content, or the algorithms, have magical powers of persuasion. But [a QAnon adherent] wasn’t looking at recipes on YouTube then slipped on a banana peel and got inadvertently pulled down the QAnon rabbit hole. Maybe they were on YouTube looking for fringe conspiracy theories or extremist religious stuff; maybe they were already into all sorts of Bible conspiracy nonsense. The internet didn’t persuade them of some foreign idea. It gave them exactly what they already believed.”

If this is the case, then any debates about whether QAnon is waxing, waning, or evolving in a post-Trump era are sort of beside the point. As Uscinski’s research bears out, a certain percentage of people (he puts it at 5-7 percent) will be predisposed to believe a certain type of anti-establishment conspiracy theory, and when they go looking, they will find it every time, in whatever form it is currently lurking. And ultimately, that means that in our collective hysteria over the QAnon phenomenon, we’ve gotten caught up in the weirdness of the ideas while perhaps losing sight of the weirdness of the people — and the fact that this potentially explosive weirdness has been an undercurrent of American society all along.

This can be hard to believe, even for other experts in the field of conspiracy thinking. “Joe knows this stuff better than really anyone else does,” says Ethan Zuckerman, the former director of the MIT Center for Civic Media and a current professor of public policy, communication and information at the University of Massachusetts. “Joe has the data and Joe’s data is good. The rest of us are just dabbling. So I’m never going to contradict Joe on what conspiracy theories are and how they happen.” But Zuckerman can’t help but think that QAnon’s outsized visibility online and in the media may be casting a “penumbra” over a wider swath of the population and “influencing 15, 20, 30 percent of people.”

Francesca Tripodi, a professor of sociology and media at UNC-Chapel Hill and a senior researcher at the Center for Information Technology, believes that the insidious use of data voids (i.e. search-engine queries that return few results until discovered by internet manipulators who then populate them with disinformation) and the way those data voids have been made to link up when someone “does their own research” on QAnon may also be making people feel more invested in the theory than they otherwise would. “When people make things themselves, the perceived value in them rises,” she explains. “It’s the Ikea Effect of misinformation.”

But it’s also possible that this pushback only further proves Uscinski’s point: The mind seeks out what it wants to be true. And blaming an insane conspiracy theory or an algorithm is easier than coming to terms with the idea that a certain percentage of Americans have, and will always have, a set of dangerous views.

Recently, Rolling Stone talked with Uscinski about what makes QAnon different from other conspiracy theories, why our “moral panic” about Q is misplaced, and what keeps him up at night.

Joseph Uscinski

Courtesy of Joseph Uscinski

You say that only a certain type of person would be predisposed to joining the QAnon movement. What makes someone likely to seek QAnon out and believe it?

A typical conversation [I have] with a journalist would be something like: “Hey, Joe, I saw this new conspiracy theory on Twitter and I’m freaked out about it because everyone’s going to see it and everyone’s going to believe it and that’s going to be bad.” And I say, “Well, did you see it?” And they say, “Yeah.” And I say, “So you must believe it then.” And they say, “No.” And I say, “Well, what makes you so fucking special? What magic shield, what superpowers do you have that protect you?”

People have a bunch of psychological characteristics — some good, some not so good. They have worldviews and identities. Those drive the conspiracy beliefs. So if somebody is sort of sociopathic, then they’re going to seek out ideas that are themselves sort of sociopathic.

Got it.

We all have an uncle that believes that Kennedy was killed by the CIA or something like that. There’s nothing abnormal about that. I mean, during the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, 80 percent of Americans bought into some form of it — it was just part of the culture. So if I said, “Hey, we’re having a party. I’m going to sit you down next to this Kennedy conspiracy believer,” would you be concerned?

No.

If I said, “I’m having a party. I’m going to sit you next to this Holocaust denier,” would you be concerned?

Yes.

So some conspiracy theories feel different precisely because they are different. And what we find is that some conspiracy theories — like Holocaust denial, saying that nobody died at Sandy Hook, things like that — they attract a different sort of person. And what we find on surveys is that those types of conspiracy theories, they appeal to people who have higher levels of psychopathy and narcissism. People who are sort of anti-social in their views, they’re picking out anti-social ideas to adopt. So it’s not the conspiracy theory doing things to them. These people are already different in their own way.

So maybe we’re mixing up the cause and the effect?

I mean, there’s this style of reporting that’s been out for a while, like, “My cousin became a QAnon and now I don’t know what to do.” These articles always start off with: “My cousin used to be so normal.” What’s really going on is the cousin was never normal or you just didn’t pay attention to the cousin and he was probably weird but you didn’t have a word to put on that.

But then you hear “QAnon” in the news. Now you can categorize what your cousin is doing as something. You’re like, “Oh, my God, this thing just happened to him.” Well, no, it didn’t just happen. Your cousin was always a wackadoo. I’m sorry.

Maybe in the past five or six years there’s just been permission for people to be more vocal about that kind of craziness?

I mean, reporters are paying more attention to this than they ever have in the past, but we can’t confuse the fact that we’re paying more attention with how much of it is there.

A lot of the coverage is saying, “QAnon is big and getting bigger and it’s far right.” None of those things are true. I’ve been polling on QAnon for three years — more than anyone else. And the support really isn’t coming from far-right people. It’s not like, “Hey, I really got into Ronald Reagan, then I read Milton Friedman, and then Satanic baby eaters.” It doesn’t follow. There’s nothing conservative or Republican about it. QAnon only likes Trump insofar as he’s an outsider who hates the ruling elite — or at least claims to.

And that’s what we find in our analyses, largely that QAnon is driven by people who just hate the entire establishment. I mean, when you watch the followers, these aren’t normal Republican people. They’re not conservative in any meaningful way. These are people who want to tear down the system because they feel alienated from it. That’s the good news: It’s small and not growing. The bad news is that a lot of the ideas it adopted are fairly popular. It’s just we haven’t paid attention. When we asked things [in polls] about views of child sex trafficking, people vastly overestimate how big it is in this country. When we ask about elite involvement in sex trafficking, people vastly overestimate that. So there are a lot of beliefs out there that are fairly widespread. But they’re not QAnon. They’re just ideas that QAnon adopted.

Is the fact that people can come together over social media or 8Chan or whatever, is that affecting how deep someone gets into these conspiracy theories in terms of how it sort of organizes their worldview and the way they spend their time?

That’s hard to know. But I would say if it was truly pulling people in deeper, then I would expect them to believe more conspiracy theories, in which case the levels would be going up on every theory. They’re not. Levels aren’t going up. For the last 10 years, I’ve measured just the general worldview, which I call “conspiracy thinking.” Do people look out the window and just generally think events and circumstances are run by conspiracies? That hasn’t gone up in the 10 years I’ve been measuring it. So, you know, it could be doing something. But whatever that something is, I should be able to find it and measure it and demonstrate that something’s gone up. Mostly what I’m finding is stability.

As far as conspiracy theories go, do you feel like QAnon is different or unique in any way?

QAnon sort of created a little game, like: “Here’s clues; go figure them out.” So it’s sort of like a decentralized cult, and it’s got activities baked into it. “Ooh, here’s some garbled language. Go decode.” That’s sort of new. But the theories themselves were not particularly new. Almost everything was old — some of it decades old; some of it was millennia old. And the news journalists covering it were freaking out like, “Oh my God, they think that there’s a deep state full of pedophiles working against the president.” There’s nothing new there. It’s incredibly boring.

We talked about the spectrum of conspiracy theories — there are ones that are kind of benign and then there are ones that are certainly more antisocial. What would lead someone to follow the former type of conspiracy versus the latter type of conspiracy?

When we ask about a whole bunch of conspiracy theories on our surveys and also measure people’s personality traits, I can tell you what lines up with what. Holocaust denial, Sandy Hook denial, those things tend to be antisocial. On the other hand, Kennedy assassination theories aren’t particularly associated with the antisocial traits. Do you think Epstein didn’t kill himself? That’s not particularly antisocial.

What about QAnon? Where does it fall?

Very antisocial. When we analyze QAnon data, what we find is that the biggest thing driving support for it or projecting support for it is having anti-establishment worldviews. If you’re sort of conspiracy-minded, if you have strong populist views, and if you have a lot of Manichean thinking — like politics is a battle between good and evil — that’s a pretty big predictor of believing in QAnon.

And then other factors are: “Do you have high dark triad personality traits like narcissism, psychopathy and Machiavellianism?” “Do you like Trump?” tends to go along with it too. “Do you overestimate the amount of child sex trafficking in the country?” Those are the sorts of things that drive that particular one.

Seeing the world as a battle between good and evil and feeling like you need to be on the good side — you don’t think that getting involved in conspiracy theories solidifies those views or augments those views? You really think that they were already there and just looking for an outlet?

I think largely the worldviews are there, and the theories themselves are sort of expressions of them. Can the belief in the conspiracy theory have an effect on the person independent of that? Probably. But it’s really hard to sort of piece those things out.

And if it weren’t one theory, they’d probably find another one.

Yeah. And that’s the thing, people are like, “How could I change someone’s mind about a theory?” And it’s like, “Well, you probably could.” But if the theory is an expression of what’s inside of them, a deeper worldview, then you’re just playing whack-a-mole.

What does engaging in a conspiracy theory do for someone who has that mindset? Are they getting constant dopamine hits of their worldview being validated? What’s in it for them?

There’s some discussion that perhaps these are coping mechanisms, but bad ones. Imagine you want to cope with uncertainty. You say, “Oh, I don’t know why the pandemic happens. I can’t sleep at night. So I’ll decide that it’s China trying to kill us all.” Well, that might ease your uncertainty, but knowing people are trying to kill you with bioweapons does not really ease your anxiety. I think it’s a lot more simple than that — it’s that people like ideas that match what they already believe.

But the algorithm certainly isn’t helping with that.

I think that’s getting overestimated, because what do algorithms do?

Give you what you already want.

Right. And nobody wants to really come to grips with the fact that people already want this. If we’re coming at this from this current lens — “this is worse than it’s ever been and people believe this now more than ever” — then you’re going to be looking for a new cause. And social media and algorithms make a perfect villain. But is it really worse now than during the Red Scare? Is it worse now than when we were drowning and crushing witches? Is it worse than that? Really? I mean, we’ve got to get some sort of grip here. This has become its own moral panic.

Maybe people just want to use the conspiracy theory as a scapegoat instead of dealing with the problem that a certain percentage of the population are psychopaths. Like, what do you do about that?

It completely undermines democracy. And that’s really fucking scary, because it’s easy to say, “Well, democracy works and, yes, we’ve had problems, but it’s only because of this exogenous force, these pesky Russians or Mark Zuckerberg and these people on Facebook and Twitter. If we just get rid of these things on the outside, we can sleep at night.” But it’s a lot more scary to realize that the real problems are on the inside. And your grandmother doesn’t have wacky beliefs because of Twitter. She always had those beliefs.

So how do we deal with it?

Well, I think there are things that could be done. One, the parties need to have better control over who they allow to run under their banner. The Republican Party should not be allowing the Trumps, and the Democratic Party should not be allowing Maryanne Williamson. If people are espousing unacceptable ideas, those people should be removed from the ballots.

Congress also needs to hold their members accountable for engaging in this sort of stuff. [Ted] Cruz and [Josh] Hawley should have been booted from the Senate for their actions. Replace them with another Republican — that’s fine. They need to hold themselves accountable before they start to censor any of us.

And I think the mainstream media needs to come to grips with its own coverage of this stuff. I mean, even when you look to mainstream TV — even if we got rid of Twitter and Facebook altogether — go watch the History Channel. It’s all alien conspiracies. Go watch Animal Planet. “The Navy Conspiracy to Kill Mermaids” was their biggest TV show of all time. Then they got Bigfoot. I thought Animal Planet was real animals. No, it’s all fake nonsense. It’s everywhere. I’m not convinced I’d want to get rid of it.

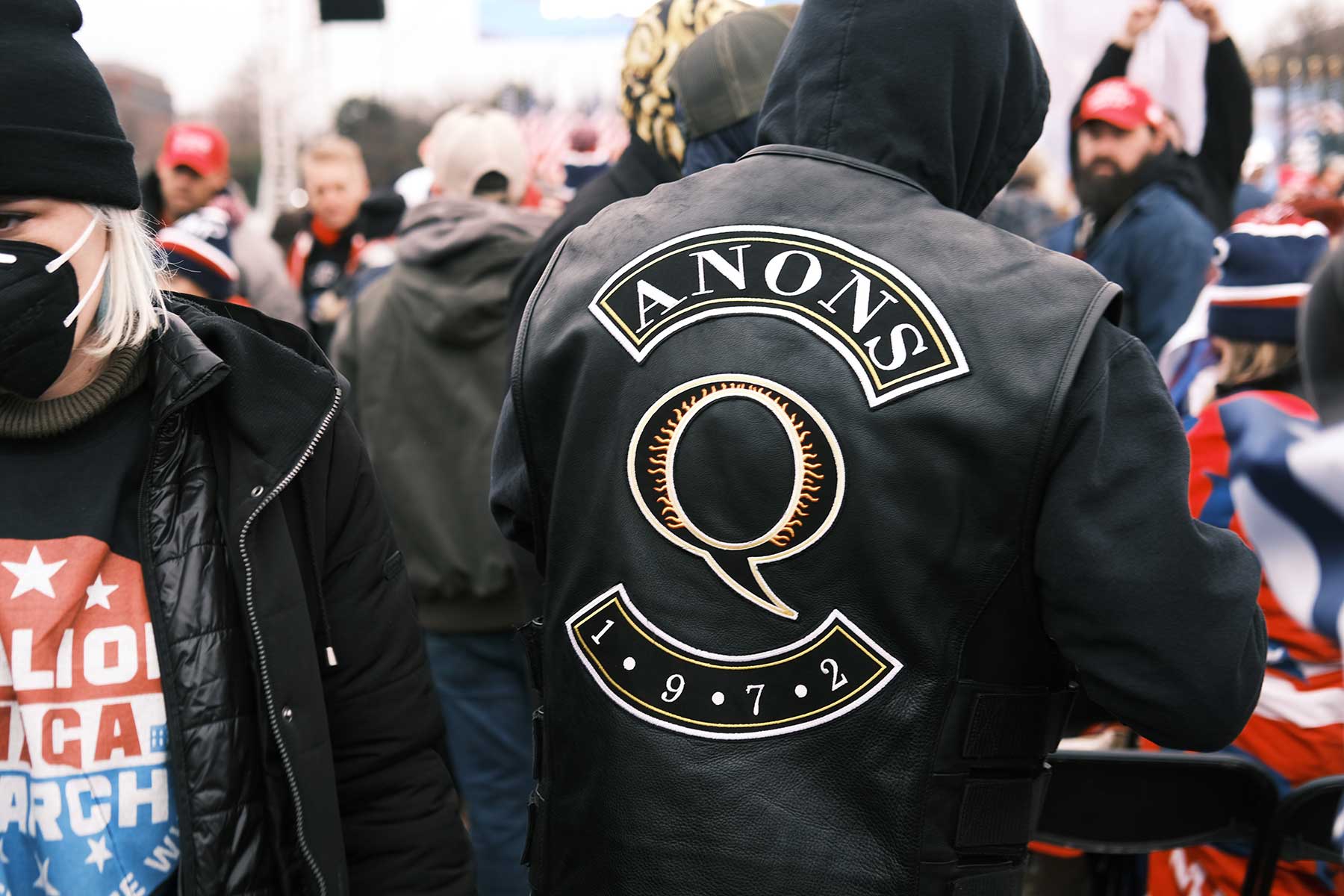

Crowds arrive for the “Stop the Steal” rally on January 06, 2021 in Washington, DC. Trump supporters gathered in the nation’s capital today to protest the ratification of President-elect Joe Biden’s Electoral College victory over President Trump in the 2020 election.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

It makes the world exciting for the rest of us?

Well, it’s good for my career [laughs]. But here’s the thing: For a lot of the people who are problematic, the problem isn’t the conspiracy theories. The problem is other stuff.

But couldn’t having those views pose a problem?

Well, if I think there’s a shadowy group trying to conspire against us, I may want to fight fire with fire. And we see examples of that. However, most people aren’t doing that. If everyone who believed a conspiracy theory committed violence on it, the streets would be covered in blood, but they’re not. These beliefs are ubiquitous; people acting on them in deleterious ways or in violent ways is incredibly rare.

So it’s not the conspiracy’s fault?

There was a guy who killed his kids because he thought they were lizard people or something. Is the guy’s problem the conspiracy theories or the fact that he’s fucking crazy?

Do you see a distinction between QAnon and a cult?

Yeah, because they’re not meeting in a singular place. They’re not being told what they can and can’t do. You don’t have that amount of social control. With QAnon, people sort of come up with whatever they want as a vehicle to follow their own fantasies, so there’s a lot of individuation. It’s cultish, but it’s not the Manson family. When you see people committing violence on these things, yes, they have the belief, but there’s generally a bunch of other stuff going on in their heads, too. Like, take Anthony Carmello, the QAnon believer who killed the Gambino crime boss. He’s not going to stand trial because he’s incompetent to aid in his own defense. The guy’s not well.

What about this sort of deprogramming that’s happening and people who come out and are like, “I was into Q, but now I see the error of my ways”? They seem to feel like they were pulled into something that wasn’t fundamentally who they are.

You know, there’s always anecdotes of these things, but when you read the write up of these, you’re not getting this full picture of whatever that person might have been into before or what their other issues might be. I mean, there was a write-up last summer about this woman who trashed the mask aisle at Target, and all they’re talking about is social media, conspiracy theories, how conspiracy theories overtook her life. You have to get to paragraph 15 to find out that, oh, by the way, she’s diagnosed with severe bipolar disorder, was off her meds for a few months, had lost her job, was facing severe anxiety and was suffering from isolation due to the pandemic. Well, OK, that should be paragraph one.

Well then why does a conspiracy theory like QAnon matter?

If there’s something that’s important about it, it’s this: What the last five years have shown us is that when political elites use conspiracy theories, they can do it strategically to pull these people into their coalition. Trump was saying a lot of nice things and Trump’s allies were saying a lot of nice things about QAnon. Why? Because they wanted to essentially pull those folks into their coalition.

Are there other examples of this historically?

Leaders will use conspiracy theories from time to time whenever it suits them. Normal mainstream presidents and presidential candidates tend to eschew it. Not entirely, but they tend to not use them. I mean, Hillary Clinton, her husband gets in trouble, she says, “It was a vast right-wing conspiracy out to get us.” It becomes a coffee mug, right?

So, yes, politicians will use this stuff a little bit. But having a major presidential candidate like Trump doing it is sort of a new thing. And it wasn’t just about one theory or one thing. It was an attempt to essentially build a new coalition within the party. Nobody in recent history has done what Trump has done and has gotten as far as he has. And I think the danger here is when our political leaders start using this stuff to build political coalitions and then to guide policy. Now Trump has opened the door for this new wing of the Republican Party of really conspiracy-minded people. People used to say, “Oh, the Republicans are into all conspiracy nonsense.” No, not that much, usually not more than the Democrats. But now the coalition has changed. And, you know, if you’re Marjorie Taylor Greene, you’re hanging out during the Trump presidency saying, “This is my time.”

What do we do about that?

Now we’re sort of stuck with it. And now even Trump’s stuck with it. Right? Because you pull these people in and you’re stuck with them. It becomes a machine that runs on itself. Trump comes out in a rally and says, “Oh, you should get the vaccine.” Everyone boos him. He can’t even control that now.

So is QAnon a scapegoat? Or should it be keeping us up at night?

To me, it’s more of a symptom than it is a problem. I mean, let’s put aside QAnon for a moment and maybe just take January 6th. One, you have a bunch of politicians who are engaging in conspiracy theories to get people riled up to go take action. And then there are some people who are willing to get riled up by conspiracy theories and go take action.

So we have the behavior of our political leaders bringing into our mainstream politics a bunch of people who have anti-establishment views and engage in anti-social behaviors. I mean, we can call it QAnon — you can call it whatever you want. But what you have there is a bunch of people with unsavory psychological characteristics and unsavory worldviews being activated by unscrupulous politicians. What the Trump presidency showed us is that our system is clearly vulnerable to that. That does keep me up at night.