Nigeria unlikely to reach ‘impossible’ 40% Covid vaccine target

It will be “impossible” for Nigeria to meet its target of vaccinating 40% of its population by the end of the year because Covid is not being taken seriously, health experts have warned.

Fewer than 1.5% of the country’s 206 million population has been fully vaccinated. But with more people killed in conflict last year and substantially more recorded deaths from malaria than Covid in Nigeria, experts believe it is further down the list of concerns for many in the country.

In September, the World Bank’s International Development Association approved a $400m (£300m) credit to speed up Nigeria’s Covid vaccination programme. The money, the World Bank said, was for safe and effective vaccine acquisition and deployment. Days later, the World Health Organization announced a strategy to help poorer countries achieve 40% vaccination coverage by the end of 2021, although WHO Africa regional director Matshidiso Moeti said that was unlikely in Africa.

“At this rate, the continent may only reach the 40% target by the end of March 2022,” said Moeti.

The feasibility of Nigeria’s vaccination plan was questioned when it was announced in January by Faisal Shuaib, head of the country’s primary healthcare agency.

Now, it looks impossible, said Prof Isa Abubakar Sadiq, director at the Centre for Infectious Diseases Bayero University Kano.

“The number of vaccines available in the country will not be enough for all those who would come forward,” said Sadiq. “If we are to achieve the target, we need more doses to be available and people need to be mobilised to come forward and take the vaccine. Not enough people are coming forward to even take the available vaccines. People are not taking the disease seriously because the severity is not as projected. The risk perception is not as it should be.”

At the start of the pandemic, experts predicted that Covid would have a devastating impact on Nigeria, with global repercussions across the continent and the world, a result of its strained health care system, the size of its population and its mobility. But reported cases and deaths have remained comparatively low.

Since the outbreak began there have been 212,500 confirmed cases, with 2,900 deaths, according to Nigeria’s Centre for Disease Control. There are under 5,500 active cases. Most quarantine centres and isolation wards that opened in the first few months of the outbreak have closed.

Malaria kills an average of 216 Nigerians a day, according to the minister of health, Dr Osagie Ehanire, and 3,326 people were killed “as a result of insecurity” in 2020, an analysis by the Cable, a Nigerian online newspaper found.

The government’s swift response to the Covid outbreak was initially applauded. Protocols designed to check the 2014 Ebola outbreak in neighbouring west African countries were quickly modified and deployed. Airports were closed and travellers were subjected to basic health screenings before other countries initiated these measures. An initial two-week lockdown in the states of Lagos, Abuja and Ogun imposed on 30 March lasted five weeks. Two weeks later, the National Human Rights Commission said, law enforcers had killed 18 people since lockdown began, while Covid had killed 12.

The low case rates came despite public indifference or reluctance to follow Covid safety rules. Mobile courts trying violators of lockdown were often overcrowded. Churches and mosques routinely disregarded the lockdowns and Covid protocols. Doubts and conspiracy theories about vaccines have deterred many.

The government quickly learned that it was impractical to keep 206 million people, 40% of whom live beneath the poverty line, at home for extended periods. During the second and third waves of Covid, lockdown was not an option. The government’s food and palliatives relief supplies meant to alleviate hunger during the lockdown, never made it to those who needed them most.

When angry youths protesting police brutality broke into the public warehouses stocked with Covid relief supplies across the country in October last year, they accused the government of hoarding the goods.

Mistrust in the government’s handling of the pandemic is widespread.

The northern state of Kano reported huge numbers of infections while pressuring the federal government for funds to fight the outbreak. But numbers dropped immediately after funds were approved. When reports emerged of inflated prices of electronic thermometers and other medical supplies being procured by government agencies, these suspicions were all but confirmed.

The low infection rates, despite widespread disregard for Covid protocols, have left experts baffled. “No one knows for certain why this is the case,” said Sadiq. “Some have attributed it to the fact that most people here have received BCG vaccines for tuberculosis, or to living in a malaria-endemic zone. Some say it might be because of the young age of the population. These are just hypotheses. I just think we are undertesting.”

The WHO has said that six in seven cases go undetected in Africa. Nigeria has conducted only 15.8 tests per 1,000.

The authorities remain committed to increasing vaccination figures. Nearly 9m doses have been administered, with the US donating 4m doses of Moderna in August.

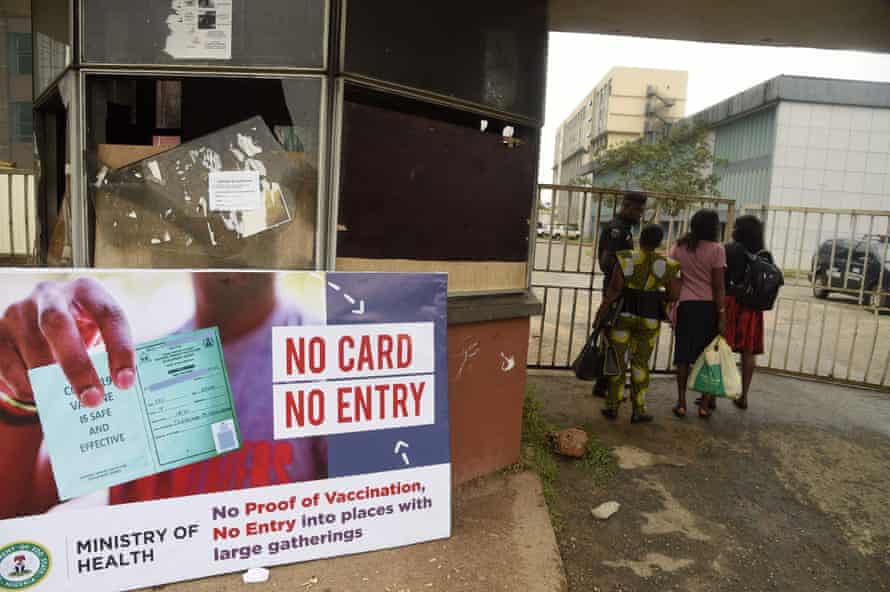

From December, government employees without proof of vaccination or a negative test will be barred from public buildings. Their numbers may be negligible in the country’s population, but the ruling was a sign that the government is desperate to move closer to its target.

*** This article has been archived for your research. The original version from The Guardian can be found here ***