This chart on conspiracy theories has gone viral. A local disinformation researcher breaks down what to know

Advertisement

In the time since Richards first designed her framework for understanding conspiracies and conspiracy theories, monumental events like the 2020 presidential election had not yet taken place nor had the coronavirus pandemic become as deeply intertwined with daily life.

“When I made this chart initially, there hadn’t even been an election yet, let alone an entire disinformation campaign that the election was stolen,” said Richards, a 25-year-old Bostonian whose TikToks on climate change have drawn millions of views. “Also back when I made this chart, vaccines weren’t out yet. There’s so much that just changed.”

Richards was prompted to create an updated pyramid as a result. Her audience was even more receptive to the chart she tweeted out last week, with it receiving “more likes and shares and everything on Twitter in one night than it did in an entire year the first time,” she said. (Richards reconfigured the infographic slightly on Sunday, which she emailed to the Globe.)

It is fair game to raise questions about common narratives and interrogate them, Richards said, but “once you get into a point where you’re not questioning anything, there’s no methodology to it, you aren’t going to experts who understand it, you refuse to accept other information about it — that can get really dangerous.”

Advertisement

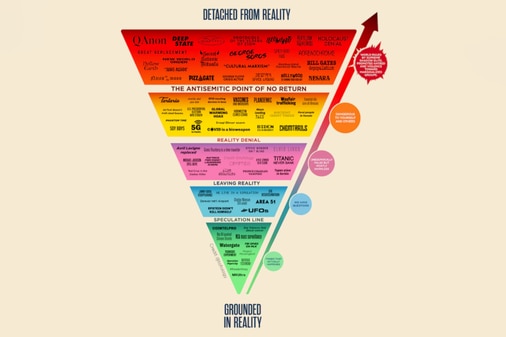

The chart is broken down into several sections, beginning with events that actually happened — including the Tuskegee Experiment and Big Tobacco lying to the American public about the deadly effects of its products — which Richards noted are “very different from conspiracy theories” as they are based in reality. She said these are “actual proven instances of people in power conspiring and abusing their power.”

As one passes the “speculation line” of the pyramid, they enter into the category where “there are still unanswered aspects” or where questions over said topics remain, and these “can be silly or can be very real,” Richards said. Further up the pyramid, the theories begin to leave reality — but have not yet entered into a zone where they could pose any major hazard to those who believe in them.

But the categories beyond the “reality denial” line contain theories that are not only perilous to those who accept them as the truth, but to the people around them, Richards said. It’s at this point that people begin to deny history, science, and medicine. The top level of the conspiracy chart, when one crosses over the “antisemitic point of no return,” is populated with theories centered around the belief that an evil group of elites “is secretly controlling the world and hiding something from everybody,” and these are “always rooted in antisemitism,” Richards said. Such theories promote both hate and violence toward marginalized groups, she said.

Advertisement

Between people hunkering down and sheltering from an unknown deadly virus to one of the most consequential elections of a lifetime, there has been a heightened sense of isolation and fear in communities across the nation, producing an environment ripe for conspiracy theories to be born and quickly spread, especially online and across social media platforms, Richards said.

“When you feel uncertain about the world it’s much easier to buy into a theory where there’s like very black and white villains and heroes,” she said. “It’s just this like evil boogeyman that you get to beat. And when you’re in a time like this where you’ve been locked inside, the world feels quite desolate and lonelier and scarier — it’s so much easier to buy into a narrative that sells you a simple solution.”

With the holiday season underway and friends and families gathering, Richards offered advice on how to talk to people who may believe in some of the theories highlighted on the chart. She recommends “to always take care of yourself first.”

“Try and approach these issues as empathetically and nonjudgmentally as possible instead of just calling them stupid for believing this,” she said. “You might as well kind of interrogate them on their beliefs and see if you can cast doubt in certain aspects of it. But I wouldn’t engage in arguments about it because you aren’t going to out-logic a belief that’s not based in logical conclusion.”

Advertisement

Shannon Larson can be reached at shannon.larson@globe.com. Follow her on Twitter @shannonlarson98.