Q&A on Monkeypox

In the midst of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, a viral outbreak once again has health officials concerned. This time, it’s monkeypox, a much less dangerous relative of smallpox.

In early May, cases of the disease began cropping up in Europe and other places outside of Central and West Africa, where monkeypox is endemic, including the U.S. Most of the monkeypox patients aren’t known to have recently traveled to endemic areas, indicating the virus is spreading person-to-person.

With hundreds of confirmed or suspected monkeypox cases reported before the end of the month, the outbreak is abnormally large. But experts say while the situation is worrying, the risk to most individuals is very low.

Here, we explain what monkeypox is, what makes the outbreak unusual, and why it’s important to take seriously but unlikely to play out like the coronavirus.

What is monkeypox?

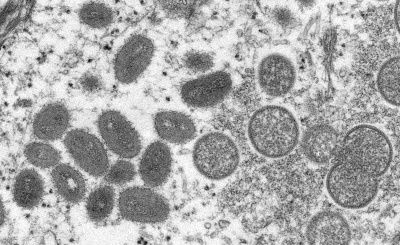

Monkeypox is a rare disease caused by the monkeypox virus, which is in the same orthopoxvirus genus and poxvirus family as the more lethal and contagious smallpox virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As with other poxviruses, monkeypox is known for a characteristic rash, and is similar in presentation to smallpox, although it will cause lymph nodes to swell and is otherwise less severe.

Monkeypox is a zoonosis, meaning that the virus is transmitted to people from animals. People typically become infected sporadically in the forested parts of Central and West Africa, after an interaction with an infected animal. Once infected, people can spread the virus to others, but that requires close contact.

Monkeypox is a zoonosis, meaning that the virus is transmitted to people from animals. People typically become infected sporadically in the forested parts of Central and West Africa, after an interaction with an infected animal. Once infected, people can spread the virus to others, but that requires close contact.

The monkeypox name stems from the disease’s discovery in lab monkeys in 1958, but monkeypox virus is not found exclusively or even primarily in monkeys. Many species, including rope and tree squirrels, Gambian pouched rats, and dormice, are able to harbor the monkeypox virus. The natural host and source of the virus is unknown, but is likely to be a rodent.

There are two main types of monkeypox virus: a West African version or “clade,” which is less severe and is the virus identified in the latest outbreak, and a more lethal Congo Basin clade.

When did the outbreak begin, and how is it unusual?

The outbreak was first recognized in the U.K. in May, but likely began earlier.

On May 13, the U.K. reported to the World Health Organization one probable and two confirmed cases of monkeypox from a single household, in people who had not traveled to a monkeypox-endemic area. About a week earlier, the U.K. had also reported a monkeypox case in a traveler from Nigeria, but it does not appear that that person spread the virus to anyone.

Other monkeypox cases were soon recognized in the U.K. By May 21, the WHO counted 92 confirmed and 28 suspected cases in Europe, Australia, Canada and the U.S.

A case tracker from the nonprofit data science initiative Global.health shows a total of 471 confirmed or suspected cases as of May 27.

The unprecedented size of the outbreak makes it unusual, along with its larger geographic distribution and the fact that many — but not all — of the cases have occurred in men who have sex with men.

As the European CDC has written, this is “the first time that chains of transmission are reported in Europe without known epidemiological links to West or Central Africa,” and these “are also the first cases worldwide reported among MSM.”

Monkeypox is extremely rare outside of Africa, and cases are usually imported with no onward transmission. The first monkeypox outbreak outside of Africa occurred in the U.S. in 2003 when imported rodents from Ghana sickened pet prairie dogs, who then spread monkeypox to humans. That outbreak included 47 confirmed or probable cases, according to the CDC.

These recent cases, however, suggest that person-to-person transmission is occurring in nonendemic countries. That has never happened before on any kind of scale, although there’s no sign that monkeypox is spreading to large numbers of people.

What information do we have about the U.S. cases, and how are they being managed?

The first U.S monkeypox case of 2022 was confirmed in Massachusetts on May 18 in a man who had traveled to Canada.

As of the evening of May 26, there have been 10 monkeypox cases in eight states: two each in Utah and Florida, and single cases in California, Colorado, Massachusetts, New York, Virginia and Washington.

CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky said in a news briefing earlier on May 26, when there were nine confirmed cases, that they were among “gay, bisexual men and other men who have sex with men,” although Virgina’s case is in a woman.

Walensky added that while some groups might be at higher risk, “the risk of exposure is not limited to any one particular group,” and she called for Americans to “approach this outbreak without stigma and without discrimination.”

It is not clear whether all of the cases are part of the larger outbreak, or if some are isolated events. The case in Virginia, for example, is in a woman who had recently traveled to a part of Africa where monkeypox is known to spread.

Walensky said in the briefing that some of the U.S. cases had recently traveled internationally to “areas with active monkeypox outbreaks,” but others had not. Because not all had travel histories, she said, “I think we need to presume that there is some community spread.”

Walensky said contact tracing was underway to limit any further transmission from the identified cases. Agency officials also said they had offered vaccines, which can work prophylactically, to those who had been exposed to monkeypox.

The CDC said in its May 23 telebriefing that there are two vaccines that could be used to prevent monkeypox in exposed individuals: an older generation smallpox vaccine, known as ACAM2000, which the government has more than 100 million doses of in the Strategic National Stockpile; and Jynneos, a newer vaccine approved in 2019 for the prevention of smallpox and monkeypox, of which there are over 1,000 doses in the stockpile.

Jynneos is the only vaccine specifically FDA-approved for the prevention of monkeypox. It is a two-dose vaccine given 28 days apart and has a better safety profile than ACAM2000, making it the preferred vaccine.

Neither vaccine contains the monkeypox virus or the variola virus, which causes smallpox. Instead, they are made of different versions of the less severe vaccinia virus, another orthopox virus. The Jynneos vaccine is considered safer because its weakened virus does not cause illness in humans and doesn’t replicate. In contrast, the ACAM2000 vaccine can be dangerous when given to immunocompromised people or those who have certain skin conditions, including eczema, dermatitis and psoriasis. Recipients of the ACAM2000 vaccine can also pass the vaccine virus on to others.

There are no FDA-approved treatments for monkeypox, but there are smallpox antivirals that may work, including tecovirimat and brincidofovir, according to the CDC.

What are the symptoms, and how severe is monkeypox?

Symptoms of monkeypox are reminiscent of smallpox and usually appear within a week or two after infection. Typically, the disease begins with a fever, headache, muscle aches, back pain, swollen lymph nodes, chills and exhaustion, according to the CDC.

A few days after the fever begins, patients develop a distinctive and frequently painful rash, which progresses from flat to raised and then fluid- and pus-filled lesions, which then scab over and fall off. The rash often begins on the face and spreads to other parts of the body. The entire illness lasts about two to four weeks.

The disease can be mild and self-limiting, but also can be fatal, as the WHO has explained. Fortunately, the virus identified in the latest cases belongs to the less lethal West African clade, which has been shown to kill about 1% of identified cases, in contrast to the Congo Basin clade, which may kill up to 10%. For comparison, the most common form of smallpox has a mortality rate of up to 30%.

Those figures may still overstate the risk of monkeypox in the U.S., since they apply to outbreaks in Africa. Nearly all cases in the developed world have been mild, experts at Johns Hopkins University have noted.

Some groups are at higher risk for more severe illness with monkeypox, including children, pregnant people and those who are immunocompromised.

Some individuals in the current outbreak have reported somewhat unusual monkeypox symptoms. The CDC, for example, has warned clinicians that not all people have had a fever and that the rashes can occur in the genital and perianal areas. One anecdotal report of a Canadian case is a man without a fever who had a small rash on his penis that did not spread elsewhere. Public health officials have also cautioned that monkeypox could be confused for chickenpox or sexually transmitted diseases such as syphilis or herpes.

In reviewing the cases in the E.U. as of May 25, the European CDC said most of the patients so far — who primarily include young men who have sex with men — have had mild disease and have had lesions on or around their genitalia. There have been no deaths.

How is the virus transmitted, and how contagious is it?

Monkeypox is initially spread to a person through an infected animal in an endemic area, which could occur through a bite or scratch or any contact with the animal’s body or lesion fluids.

Once humans are infected and have symptoms, they can pass the virus on to others through close physical contact. According to the WHO, the rash and the scabs and fluids from the skin lesions are especially infectious, which means contaminated clothing or bedding can also spread the virus.

Monkeypox is also spread through large respiratory droplets, probably because lesions in the mouth render saliva infectious. Because these larger droplets don’t travel more than a few feet, though, it takes a lot of face-to-face contact to spread the virus, the CDC explains.

Because a high level of contact is required, monkeypox is not considered very contagious, unlike the coronavirus.

Although some have speculated whether monkeypox could be sexually transmitted, given the large number of cases in men who have sex with men, it’s not known if the virus can be spread through semen or vaginal fluids. But as Andrea McCollum, the CDC’s expert on monkeypox, has said, close contact “certainly occurs during intimate contact.”

The WHO has similarly noted that direct skin-to-skin contact can spread the virus, and monkeypox rashes are also sometimes located in the mouth or on genitals, “which is likely to contribute to transmission during sexual contact.”

According to the CDC, a person is contagious from the time the rash starts to when the scabs fall off. WHO has said that it’s “not clear” whether people without symptoms can spread the virus.

How concerning is this monkeypox outbreak?

Experts are in general agreement that the monkeypox outbreak is something to be aware of and take seriously, but not something that people need to panic over or even worry that much about.

“On an individual level, for most people, it’s something that won’t impact them,” Anne W. Rimoin, an epidemiologist at UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health who has studied monkeypox, said in an interview with Andy Slavitt, a former COVID-19 response adviser to President Joe Biden, on his “In the Bubble” podcast. “Your average person is very unlikely to come into contact with a potential case of monkeypox,” she said, adding that monkeypox is still a rare occurrence and “can be controlled.”

The WHO has emphasized that monkeypox is not spread easily between people and has said the risk to the general public is “low.” But increased awareness, the agency says, will help stop further transmission.

Agency officials do expect more cases, but for those concerned that monkeypox could become the next COVID-19, experts say that’s unlikely.

Luis Sigal, an orthopox researcher at Thomas Jefferson University, told us it was “extremely unlikely” that monkeypox would cause a pandemic like the coronavirus. While it’s impossible to rule out that things might unfold in an unexpected way, “the risk is not nearly as high with SARS-CoV-2,” he said, referring to the virus that causes COVID-19.

In part, that’s because the viruses are very different. Again, monkeypox is much harder to spread, and the virus is physically much larger, which Sigal said could make it difficult for the virus to travel in larger respiratory droplets.

“It’s a very heavy virus,” he said, adding that poxviruses, which are made of double-stranded DNA, in contrast to SARS-CoV-2’s single-stranded RNA, “have some of the biggest viruses in nature.”

Monkeypox virus, too, does not mutate nearly as rapidly as SARS-CoV-2, Sigal said. That would mean that even if monkeypox became more widespread, populations would be much less likely to have to deal with new variants in short succession.

The overall risk is lower as well because so much more is known about monkeypox than there was about COVID-19 — and some vaccines and treatments already exist.

“We have vaccines, we have therapeutics. We know a lot about this virus, we’ve been studying it for decades,” Rimoin said. “This is not a completely new scenario. We’re dealing with something that’s known, something that we can wrap our arms around.”

“Even if the things have changed slightly,” she added, “that’s an important part of the knowledge base, but it doesn’t change fundamentally how we fix this problem.”

There is the possibility with this outbreak that monkeypox could spread back into an animal, creating a new reservoir for the virus in the U.S. and elsewhere. But CDC officials are hopeful that won’t happen, noting in a May 23 telebriefing that even in 2003 with the infection of pets in many people’s households, the virus did not take root and become endemic.

“While we continue to watch, our 2003 outbreak gives us data to not be as worried,” Jennifer McQuiston, deputy director of the CDC’s division of high consequence pathogens and pathology, said.

Why is there a monkeypox outbreak now?

Scientists don’t know, but several factors could be in play.

The first is just that monkeypox cases have become more common in the last decades and particularly in recent years, when Nigeria began observing an uptick in cases in 2017 that has yet to subside. That has led to more imported monkeypox cases in general, including two imported cases to the U.S. from Nigeria in 2021.

The reasons behind this surge are not fully understood, but likely involve a lower degree of population immunity to monkeypox since the eradication of smallpox in 1980 and the end of smallpox vaccination. Because of similarities in the viruses, smallpox infections and vaccination afford some protection against monkeypox, but over time, more and more of the population does not have any protection.

“In and of itself, this is not surprising,” said Rimoin. “We have a population that no longer has immunity to poxviruses. If it gets introduced, we’re going to see cases.”

In 2010, Rimoin and colleagues published a study in PNAS showing a dramatic increase in the frequency of monkeypox cases since the end of smallpox vaccination campaigns — and a more than fivefold increase in risk of monkeypox among the unvaccinated compared with the vaccinated.

Other factors, including deforestation, climate change, and changes in population movements and hunting habits might also have increased the likelihood of spillovers as humans encounter more wild animals.

As for why monkeypox has spread quite so widely in the last month, some epidemiologists suspect that a couple of rave-like parties in Spain and Belgium that were attended by men who have sex with men could have seeded outbreaks in multiple countries. It’s also possible that monkeypox has been spreading quietly without anyone noticing, Rimoin said, and such events simply helped amplify the outbreak.

Indeed, the timing may have to do with loosening travel restrictions from the COVID-19 pandemic, David Heymann, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, has said.

“If you look at what’s been happening in the world over the past few years, and if you look at what’s happening now, you could easily wonder if this virus entered the U.K. two to three years ago, it was transmitting below the radar screen, [with] slow chains of transmission,” Heymann told STAT News. “And then all of a sudden everything opened up and people began traveling and mixing.”

It’s important to note that while many of the latest monkeypox cases have been among men who have sex with men, there is no reason to think that such men are uniquely susceptible. And indeed, public health officials have said that anyone, regardless of sexual orientation, can get or spread monkeypox if they come into contact with the virus, so anyone with suspicious symptoms should be evaluated.

Is there something unique about this specific monkeypox virus that would account for its unusual spread?

There is no obvious change to the viral genome that would suggest the monkeypox virus behind the current outbreak is better at person-to-person transmission than past viruses, but it is a possibility.

Based on the limited number of monkeypox viral sequences that scientists have analyzed so far, all of the outbreak viruses are virtually identical but differ from their closest known relatives, which were responsible for outbreaks in 2018 and 2019, by around 50 nucleotides. That’s more than would be expected, since monkeypox viruses mutate quite slowly, with only about one or two changes per year.

As Trevor Bedford, a computational biologist studying viral evolution at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, said on Twitter, the “~47 mutations suggest at least [the] potential” for there to be a “genetic component that would facilitate human-to-human transmission of the current outbreak viruses.” Still, he said, it was “unclear.”

Scientists will have to look more closely at those viral changes to determine if any of them occur in genes that could plausibly increase the transmissibility of the virus, and then do experiments in the lab to further investigate, Jefferson’s Sigal told us.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, 202 S. 36th St., Philadelphia, PA 19104.