The Potential of a ‘Hot War’ Between the U.S. and Russia

This is an edition of Up for Debate, a newsletter by Conor Friedersdorf. On Wednesdays, he rounds up timely conversations and solicits reader responses to one thought-provoking question. Later, he publishes some thoughtful replies. Sign up for the newsletter here.

Question of the Week

Russia’s murderous invasion of Ukraine is ongoing. So is the oppression of Uyghur Muslims in Chinese concentration camps. China also has designs on subjugating the people of Hong Kong and potentially Taiwan. And with wheat production falling due to war and weather, a catastrophic hunger crisis in poor countries is very likely. What responsibility, if any, do the United States or individual Americans have to help innocents around the world afflicted in ways like these? Send your answers to conor@theatlantic.com.

Conversations of Note

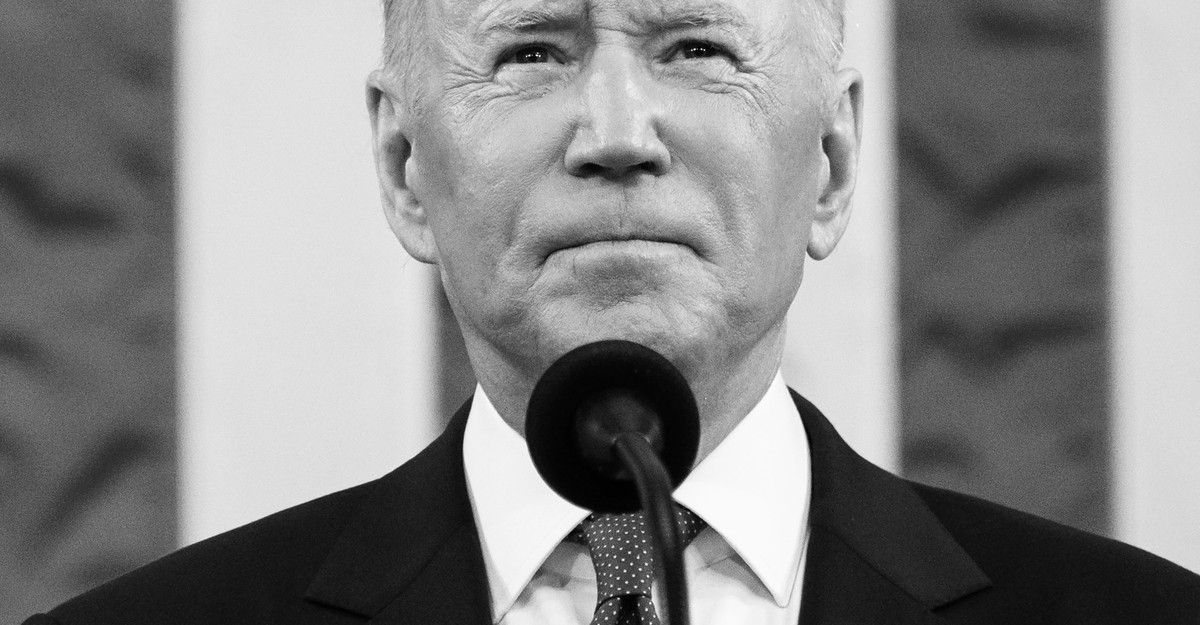

The war in Ukraine and its potential to escalate is top of mind for me this week as President Joe Biden declares that he will send advanced rocket systems to the country and the European Union and the United Kingdom collaborate to shut Russian oil shipments out of key insurance markets.

Is the West sleepwalking toward a hot war with Russia? Christopher Caldwell thinks so, and makes the case that if Europe finds itself at war, then America will bear part of the blame:

Even if we don’t accept Mr. Putin’s claim that America’s arming of Ukraine is the reason the war happened in the first place, it is certainly the reason the war has taken the kinetic, explosive, deadly form it has. Our role in this is not passive or incidental. We have given Ukrainians cause to believe they can prevail in a war of escalation.

Thousands of Ukrainians have died who likely would not have if the United States had stood aside. That naturally may create among American policy makers a sense of moral and political obligation—to stay the course, to escalate the conflict, to match any excess.

The United States has shown itself not just liable to escalate but also inclined to. In March, Mr. Biden invoked God before insisting that Mr. Putin “cannot remain in power.” In April, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin explained that the United States seeks to “see Russia weakened” …

Mr. Biden’s suggestion that Mr. Putin be tried for war crimes is an act of consummate irresponsibility. The charge is so serious that, once leveled, it discourages restraint; after all, a leader who commits one atrocity is no less a war criminal than one who commits a thousand. The effect, intended or not, is to foreclose any recourse to peace negotiations.

David C. Hendrickson asserts that the U.S. “is closer to war with Russia than at any time in the past three decades, and more so than most times during the Cold War.” He writes of the coming months:

Ukraine’s leaders have demanded that Russia abandon both Crimea and the Donbass, then submit to reparations and a war crimes trial for Vladimir Putin. How far America’s prodigious aid for Ukraine, at $54 billion and counting, will go in enabling these goals is unclear.

Russia appears on the cusp of encircling important pockets of Ukrainian forces in the East—a major defeat for Ukraine that would lead to recriminations—but Ukraine also promises to raise a million-man army paid for by the USA, and ready for offensives in the summer. If Ukraine does go on the offensive, eyeing its lost territories, it can only do so with stout American assistance. In that effort there are lots of paths to a real war between the United States and Russia. The celebrated realist Hans J. Morgenthau wrote, in his rules for effective diplomacy, that you should never let a weak ally make your decisions for you. The Washington establishment rises every morning seemingly determined to violate that injunction.

But Anne Applebaum argues that it would be unwise to negotiate in a manner that gives Vladamir Putin an “off-ramp” rather than a beatdown:

Our goal, our endgame, should be defeat.

In fact, the only solution that offers some hope of long-term stability in Europe is rapid defeat, or even, to borrow [French President Emmanuel] Macron’s phrase, humiliation. In truth, the Russian president not only has to stop fighting the war; he has to conclude that the war was a terrible mistake, one that can never be repeated. More to the point, the people around him—leaders of the army, the security services, the business community—have to conclude exactly the same thing. The Russian public must eventually come to agree too.

Spiegel International argues that defeating Russia won’t be easy now that it has altered its strategy:

The strategy Putin has pursued in the Donbas has involved heavy artillery fire against Ukrainian positions before then slowly advancing. Supply lines have also been firmly established. Germany’s foreign intelligence service, the BND, estimates that Russia is currently able to send up to 300 tons of munitions to the front every day—sufficient for a huge amount of firepower. At the same time, says the German government, Western sanctions on the import of Russian energy have not proven as painful as hoped. India alone more than doubled its oil imports from Russia from March to April. A leading German official says that the Russian war machine will only begin sputtering once the embargo results in a lack of important electronic parts necessary for modern weapons systems.

How to Effect Change in America

Michael Lind argues that many Americans have a faulty approach that he calls “wingnut theory”:

On left and right, the wingnut theory holds that making public policy is a three-step process: First, you and your ideological allies take over a wing of one of America’s two major parties and draft a comprehensive platform with positions on all issues, foreign and domestic. Second, your wing of the party takes over the party as a whole. Third, your triumphant one-wing party defeats the other party, takes over the entire government, and imposes its comprehensive platform on America in a burst of supermajority legislation. Utopia ensues. The wingnut theory comes in a presidential as well as a congressional version. The only minor difference is that a caesarist president in the supposed mold of Washington, Lincoln, or FDR brings about the nation-transforming policy revolution in a flurry of executive orders in the first 100 days of the administration. Never mind that nothing like this ever actually happened under Washington, Lincoln, or FDR.

He contends that elite factions putting key personnel in the federal bureaucracy is how change actually happens.

The Most Important Civil Liberty

The ACLU’s David Cole says the people accusing the civil-liberties organization of backing away from defending free speech are wrong––and publishes a stirring defense of free speech in The Nation, where he writes, “Yes, it extends to the powerful and hateful as well as the marginalized. That’s the thing about rights. They apply universally. But if you are in the minority, whatever side you are on, there is no more important safeguard. None.”

A bit more:

We believe that even if free speech and equality can appear to be in tension in particular contexts—such as the regulation of hate speech or campaign finance—at a deeper level speech rights and equality are mutually reinforcing. Those who stand with us for racial justice, women’s rights, equal dignity for LGBTQ individuals, immigrants’ rights, and the rights of people with disabilities can achieve those ends only by exercising the freedoms that the First Amendment guarantees. Free speech and association undergird every social justice movement in this country. When Martin Luther King Jr. reminded us that “there is no gain without struggle,” he was talking as much about the First Amendment as the 14th. Those who would sacrifice speech to attain equality will achieve neither.

The critics, in short, are wrong. We remain committed to the principled defense of speakers with whom we fundamentally disagree.

I hope that he’s right, and that Lara Bazelon is wrong, but some of her arguments remain unanswered.

Greenwashing

“Americans support recycling. We do too,” a former EPA administrator, Judith Enck, and a chemical engineer, Jan Dell, write. “But although some materials can be effectively recycled and safely made from recycled content, plastics cannot. Plastic recycling does not work and will never work.”

Provocation of the Week

The cultural critic Susie Linfield has been thinking about graphic images at least since writing her exceptional book “The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence.” Now she’s applying that expertise to the school shooting in Texas, and suggesting that maybe we ought to see photographs of the bodies of children riddled with bullets.

She writes:

The question of how much violence we should see, and to what end, is almost as old as photography itself. But the question gains urgency in our age of unfiltered immediacy—of the 24-hour news cycle, of Instagram and Twitter, of jihadi beheading videos, of fake news and conspiracy theorists and of repellent sites like BestGore, which revel in sadistic carnage. What responsibilities does the act of seeing entail? Is the viewing of violence an indefensible form of collaboration with it? Is the refusal to view violence an indefensible form of denial?

In the case of Uvalde, a serious case can be made—indeed, I agree with it—that the nation should see exactly how an assault rifle pulverizes the body of a 10-year-old, just as we needed to see (but rarely did) the injuries to our troops in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. A violent society ought, at the very least, to regard its handiwork, however ugly, whether it be the toll on the men and women who fight in our name, on “ordinary” crime victims killed or wounded by guns or on children whose right to grow up has been sacrificed to the right to bear arms.

But seeing and doing are not the same, nor should they be. Images are slippery things, and it is both naïve and arrogant to assume that an image will be interpreted in only one way (that is, yours) and that it will lead to direct political change (the kind you support).

Thanks for your contributions. I read every one that you send. By submitting an email, you’ve agreed to let us use it—in part or in full—in the newsletter and on our website. Published feedback may include a writer’s full name, city, and state, unless otherwise requested in your initial note.

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from The Atlantic can be found here.