Russia & the Eternal Pandemic

Riley Waggaman

In April 2021, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced ambitious plans to keep the country safe from future coronavirus-like plagues.

“In the event of an infection as dangerous as the coronavirus or perhaps more, God forbid, Russia must be ready within four days—precisely within four days—to develop its own test systems, and in the shortest possible time to create an effective domestic vaccine, to start its mass production,” Putin said during a speech to the Federation Council, Russia’s upper house of parliament.

The rapid development of tests and vaccines would be part of a “powerful and reliable shield in the field of sanitary and biological safety” that should be functional in the next three years and fully operational by 2030, the Russian leader told lawmakers.

Although far from completion, Russia’s “Sanitary Shield”—a network of laboratories and border checkpoints tasked with ensuring the country’s biosecurity—sprang into action in response to the curious emergence of monkeypox in early May.

In less than three weeks, Rospotrebnadzor, Russia’s agency for “human welfare,” created a monkeypox PCR test and applied to register a genetic smallpox vaccine.

Very impressive.

But will this “shield” actually keep Russians safe and healthy? Or is it just another gross scam? We investigated and you will probably not be even the tiniest bit surprised by what we found.

“An epidemic without a lockdown”

Deputy Prime Minister Tatyana Golikova—a passionate advocate for ineffective and potentially dangerous medications—has played a central role in Sanitary Shield’s development.

“Today we believe that this project is one of the most important, because this won’t be the only pandemic that we will have to face in our lives,” Golikova said while speaking at the New Knowledge conference in Moscow in September.

“In addition to the research centers, infrastructure will also be laid down to test new arrivals to the country. We are planning to create, at checkpoints along the whole border of the Russian Federation, express diagnostics units that can test for any virus within an hour,” she explained.

December 14, 2021: “From 2022, from January, we will begin the implementation of the Sanitary Shield federal project, under which 99 checkpoints across the state border will be equipped with an automatic system for passing passengers, as well as mobile devices for reading data about people arriving on the territory of the Russian Federation,” Golikova said. (source)

As for Sanitary Shield vaccine development: Golikova cited Sputnik V as a model to emulate, dismissing completely accurate accusations that Russia had rushed the drug’s development and safety testing.

“Today, science and engineering has reached a level that allows us to build [vaccines] like a designer, using biological, mathematical and other methods,” the deputy prime minister claimed.

Rospotrebnadzor chief Anna Popova, speaking last June at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, was similarly optimistic about Sanitary Shield’s potential, describing the program’s slogan as: “An epidemic without a lockdown.”

“This is the task that we have set. We must ensure the functioning of the country, both the economy and social relations, by preventing the spread of infection,” she said. “The task is very difficult, but we have prioritized it: new conditions, new rules you follow, that’s all.”

Investing in a global mechanism

Russia is so confident in its Sanitary Shield that it has already pitched the idea to other countries.

Commenting on the results of the G20 summit held in Rome at the end of October 2021, Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov said he had lobbied other nations to adopt Moscow’s approach to biosecurity.

“Russia is helping other countries to fight the pandemic, both on the bilateral and on the multilateral level: in the form of delivering vaccines, personal protection equipment, medicines and providing other technical assistance,” Siluanov told the gathering of G20 ministers.

The Russian finance minister also informed his counterparts about “measures that Russia is implementing on the national level, particularly the ‘Sanitary Shield’ project” and “suggested creating a similar mechanism on the global level.”

Taking biosecurity to the next level. (source)

Although recent geopolitical events have undoubtedly complicated Russia’s relationship with its (former?) “western partners,” Siluanov’s dream of a global Sanitary Shield should not be dismissed as mere fantasy.

Tellingly, the development of the fabled Shield is on the agenda at this year’s St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. Described as “Russia’s answer to Davos,” SPIEF has boasted VIP guests such as Klaus Schwab and Henry Kissinger.

Klaus Schwab: Russia is one of the responsible global regulation leaders #SPIEF https://t.co/jgB6KXPqIE pic.twitter.com/FF7BSniGEd

— SPIEF (@SPIEF) June 13, 2017

On June 17, a SPIEF panel will discuss how the Sanitary Shield program could help Russia become a leader in “biological safety.”

According to a description of the event on SPIEF’s website, the hope is that mass testing and vaccination will negate the need for economy-ruining lockdowns, thereby promoting “sustainable economic and social development.”

If lockdowns don’t work (and they don’t), why is the Russian government creating the false choice between vaxxing and house arrest? Nobody knows:

Preparedness for threats to people’s health has become one of the fundamental factors for sustainable economic and social development. A month of lockdown could lead to zero growth in the economy for the year…

The government’s investments in a ‘sanitary shield’ have a multiplier effect by attracting additional investments in science, the development of biotechnology, the production of tests and vaccines…

In what specific areas of biological safety can Russia become a leader and create standards? What mechanisms are needed to multiply investments in the ‘sanitary shield’?

But what kind of investments are we talking about, specifically? And are there opportunities for “healthy” profits?

Russia’s PCR racketeers

The PCR testing market in Russia reportedly rakes in at least $1.7 billion per annum—a new boon for biomedical and pharmaceutical companies. Thanks to Sanitary Shield, PCR tests may become a bottomless pot of gold for firms that win government tenders.

As Russian outlet Octagon revealed in a must-read report from September, all the major players in the country’s PCR market are extremely well-connected and have been the main beneficiaries of the “pandemic.”

For example, Generium, part of oligarch Viktor Kharitonin’s business empire, was among the first firms to enter the PCR test racket. The company received the right to sell tests on April 2, 2020, only a few weeks after the official start of the “pandemic” in Russia. Kharitonin was showered with rubles after the Russian health ministry listed one of his highly dubious drugs, Arbidol, as a treatment for coronavirus.

Another major supplier of PCR tests is R-Pharm, which teamed up with Russia’s sovereign wealth fund (RDIF) to manufacture vaccines and COVID “treatments.”

As we documented in a previous article, R-Pharm made huge profits after Russia’s health ministry listed its HIV medication, Kaletra, as an approved treatment for COVID. Despite there being zero evidence that Kaletra was effective against the new virus, billions of rubles in public funds were spent on procuring the drug for government medicine stocks.

R-Pharm’s profile on the World Economic Forum’s website (source)

Sistema-BioTech, controlled by Davos-friendly oligarch Vladimir Evtushenkov, also has a piece of the PCR pie.

The other two big players are run by the Russian government. “Vector-Best” operates under the umbrella of Anna Popova’s Rospotrebnadzor; the health ministry’s Gamaleya Center, famous for developing an unproven genetic injection, is also involved in the PCR test market, Octagon reported.

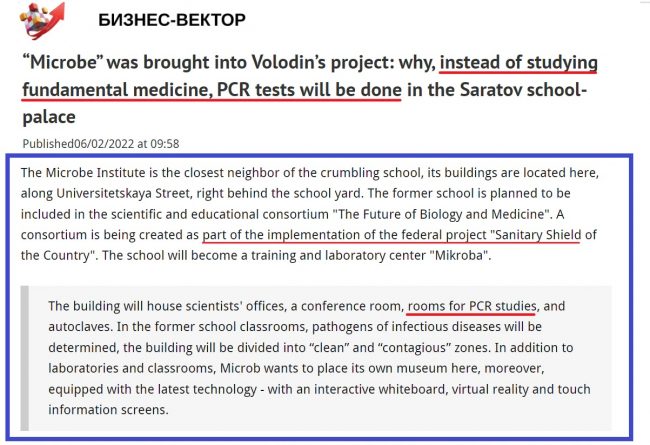

“PCR studies”

Science follows the money—it’s a universal truth. In Russia, the creation of a network of PCR-centric “biosafety” laboratories means that a new generation of medical professionals will need to be trained in the art of swabbing.

On June 2, Russian media reported that a destitute medical school would be given new life as a Sanitary Shield-affiliated education institution.

And what will young Russians learn at this fancy new school? “PCR studies.”

Reorganizing medicine and “biosafety” around a “test” that is not fit for purpose: safe and effective.

If you want a picture of the future, imagine a giant Q-tip swabbing your body-holes—forever.

Darn it.

Riley Waggaman is your humble Moscow correspondent. He worked for RT, Press TV, Russia Insider, yadda yadda. In his youth, he attended a White House lawn party where he asked Barack Obama if imprisoned whistleblower Bradley Manning (Chelsea was still a boy back then) “had a good Easter.” Good times good times. You can subscribe to his Substack here, or follow him on twitter or Telegram.

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from OffGuardian can be found here.