Putin’s New Propaganda Battle | Wilson Quarterly

From fiery speeches to movie reels to TikTok, propaganda is a critical part of war. It is used to motivate citizens, glorify soldiers, justify military action, and win support from global allies. The war in Ukraine highlights both Russia turning its long-term grievances into open conflict as well as the limits of information warfare.

The outcome of traditional combat is clear in terms of conquered territory. The results of information warfare are much harder to measure. While Russia has delivered a propaganda bombardment alongside the tanks and missiles in its war on Ukraine, its propaganda battle has met with even more limited success than its military attack.

The Kremlin has struggled to find a meaningful narrative to justify the invasion of its democratic neighbor. Additionally, Ukrainian officials and citizens have shown a creative ability to leverage 21st-century communication strategies, while the Russians seem mired in propaganda of the century past. Finally, the conflict has attracted extensive documentation, with a massive number of journalists and heavy social media attention, putting a bloody conflict that is blamed on the Russians in front of a huge global audience.

While part of the problem is the weak rationalization for an invasion, the other key challenge for Russia is the Ukrainian counternarrative.

This suggests that while war propaganda goals remain the same, modern information warfare tactics have changed. In this case, Russia seeks to brand itself as a powerful international force rather than a corrupt petrostate, while Ukraine is fighting for its very survival.

Evidence also suggests that while historic Russian strategic narratives could have predicted the invasion, the war in Ukraine represents a new front in information warfare that relies more heavily on conspiracy theories than traditional grievances against the West. Until Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Russian propaganda narratives were fairly predictable and reflected four key messages: Russia is a resurgent global power; the United States and NATO are out to destroy Russia; democracy is flawed and failing; and Russia will protect Russians wherever they live.

All four strategic narratives—the ways in which nations formulate their desired vision and goals for political outcomes—could predict an invasion of neighboring Ukraine. Russian president Vladimir Putin has long considered Ukraine as a thorn in his side for embracing democracy. In 2014, Russia seized Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula and invaded the Donbas region on false claims of supporting an ethnic Russian uprising there.

Putin introduced a false conspiracy narrative to rationalize the 2022 invasion: the need to “de-Nazify” Ukraine by invading the country. While all narratives tend to deviate somewhat from reality, this conspiracy theory reached Orwellian heights of illogic and had little success.

While it is hard to gauge what Russians think of the war, there is little acceptance globally of Russian assertions that they are freeing Ukrainians from the grip of Nazi leaders. The Russian propaganda front is more successful domestically in claiming that Russians are a victim of a US-led campaign to wipe Russia from the map, executed by expanding NATO. This dovetails well with popular conspiracies that a group of Western elites is manipulating world affairs. Disinformation is particularly effective when linked to shared conspiracy theories.

While part of the problem is the weak rationalization for an invasion, the other key challenge for Russia is the Ukrainian counternarrative. Not only does Ukraine have a better role in international discourse as a democratic state that is the victim of unprovoked Russian aggression, Ukrainian leaders are far better at leveraging online and traditional media to tell their story and foster strong emotional support.

This is in part because Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy, a former actor, is an exceptionally good speaker and has a powerful social media voice. In one of his most iconic videos, which is less than 40 seconds long, he merely stands with his ministers at night in Kyiv and says, “We are here.” Voices from Ukraine are amplified because of widespread coverage of the war itself. Zelenskyy benefits from the hybrid media system, in that his videos are widely distributed by global mass media as well as across multiple popular social media channels.

The Ukrainian government has encouraged citizen journalism and witnessing, while Russia has limited and banned social media more broadly.

An article in Wired suggests that the videos produced by Zelenskyy and his communications team have created a “serialized manifesto” that pushes back against nationalistic Russian rhetoric. In particular, Zelenskyy’s video on the eve of the invasion in February 2022 says, “You are told that we hate Russian culture. But how can you hate a culture? Any culture?” This signaled that Zelenskyy avoided countering Russian propaganda with his own anti-Russian messages and rejects the Russia-against-the-world narrative from the Kremlin. Overall, the article notes that Zelenskyy has been able to construct “a grand narrative that attracted aid from around the world” as he “pulls off a rhetorical rout comparable to any heroism on the battlefield.”

Yet, Zelenskyy and the Ukrainian government do not have to rely on social media alone, as they also benefit from traditional media war coverage. The Ukrainian military, unlike most modern armies, has not limited the access of reporters to the battlefield. While journalists have paid a horrific cost to get this story—12 had been killed by June 2022—the world has unprecedentedly graphic and timely coverage of the ravages of this war. Much of the world has condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its coverage in the West has been overwhelmingly negative for Russia in both traditional and social media.

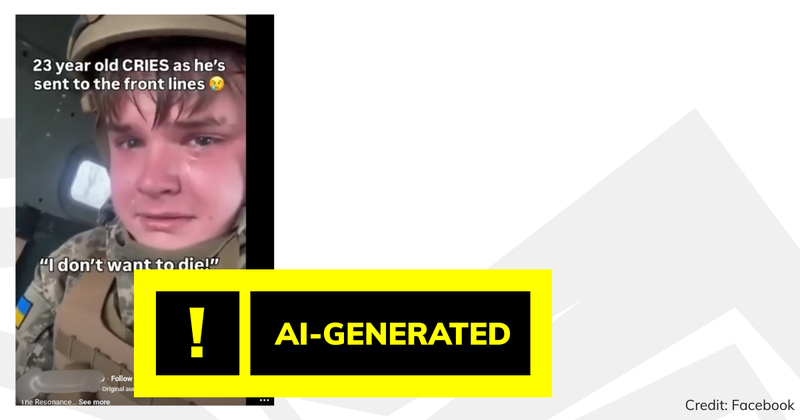

At the same time, the Ukrainian government has encouraged citizen journalism and witnessing, while Russia has limited and banned social media more broadly. Ukrainian social media content has gone viral and dominates online. The logic of social media communication—the need to be instantaneous, visually compelling, raw, and native—plays strongly in the favor of the Ukrainians.

Ukraine’s effective campaign on multiple fronts of the information war—from Zelenskyy’s social media presence and its amplification by the hybrid media system, to citizen journalism and the military’s openness to war correspondents—may be contributing to Russia’s continuing slide in the court of global opinion.

What does Russian hybrid warfare—the fusion of conventional and unconventional “instruments of power and tools of subversion”—show the United States about Russian propaganda? First, Russia’s animosity toward Ukraine was signaled both by the persistent anti-West, pro-Russia strategic narratives emanating from the Kremlin. Second, Putin heralded the actual invasion by inserting a new conspiracy narrative of Ukrainian “Nazis” into the public discourse.

The hybrid war in Ukraine demonstrates how both authoritarian and democratic states have certain advantages in modern information warfare.

On one hand, this means that knowing and tracking Russian strategic narratives is a vital part of understanding Russian state intentions. Russians make no secret of their global ambitions and have invested heavily in transmitting these narratives around the world, both overtly and covertly. The shift in narrative by adding the Nazi conspiracy element signaled a change in military action from a limited war in Ukraine in the Donbas to a full-scale invasion of the country. The United States should continue to monitor narratives, especially as Russia threatens other neighboring states.

Russia went off script with fantastical justifications for its invasion of Ukraine. Now that the world is watching, Russia’s 20th-century propaganda strategy is much more challenged—particularly by extensive war coverage. In contrast, Ukraine is effectively leveraging far better branding and use of social media, demonstrating a 21st-century strategy that is not within the grasp of the authoritarian Russian regime whose leadership is out of touch with modern social media. Because Ukraine is winning the information war, it makes it more likely it will get the equipment it needs to win the war on the battlefield.

We can’t know the outcome of the war in Ukraine, although we do know it has been far more of a struggle in terms of both conventional and information warfare than the Kremlin predicted. Much of the outcome will depend on how much weapons and aid are provided to Ukraine, which is to a degree dependent on the strategic narratives that leaders in other countries choose to support. So far, Russia has offered little in the way of rationalization of the conflict, while the Ukrainians have showcased their humanity and suffering in ways that resonate broadly with global publics and elites alike.

The hybrid war in Ukraine demonstrates how both authoritarian and democratic states have certain advantages in modern information warfare. Russians are more successful at breeding conspiracy theories in the shadows of websites and social media, away from the gaze of the international media, as the Kremlin enjoys almost total control of top-down messaging in Russia. The success of the Ukrainian information campaign, however, relies on keeping the world’s attention focused on the war as the conflict drags on—and the translation of that attention into tangible military support.

No matter what the final outcome, it’s clear that strategically deployed propaganda remains a critical tool in winning over hearts and minds during battle. It is also clear that even with a recognized winner in the war of words and images, propaganda is not enough to win the war itself.

Professor Sarah Oates is a Distinguished Scholar-Teacher and Senior Scholar at the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland (College Park). A scholar in the field of political communication and democratization, a major theme in her work is the way in which the traditional media and the internet can support or subvert democracy in places as diverse as Russia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. She was a Fulbright scholar in Russia as well as a fellow at the Kennan Institute at the Wilson Center. More details on her research can be found at www.media-politics.com.

Cover photo: A Russian journalist interrupts a live TV state media broadcast with a “no war” protest sigh, telling viewers not to believe the lies. Screenshot.