A Trump-Backed Veteran Ran Hard to the Right, Only to Be Outflanked

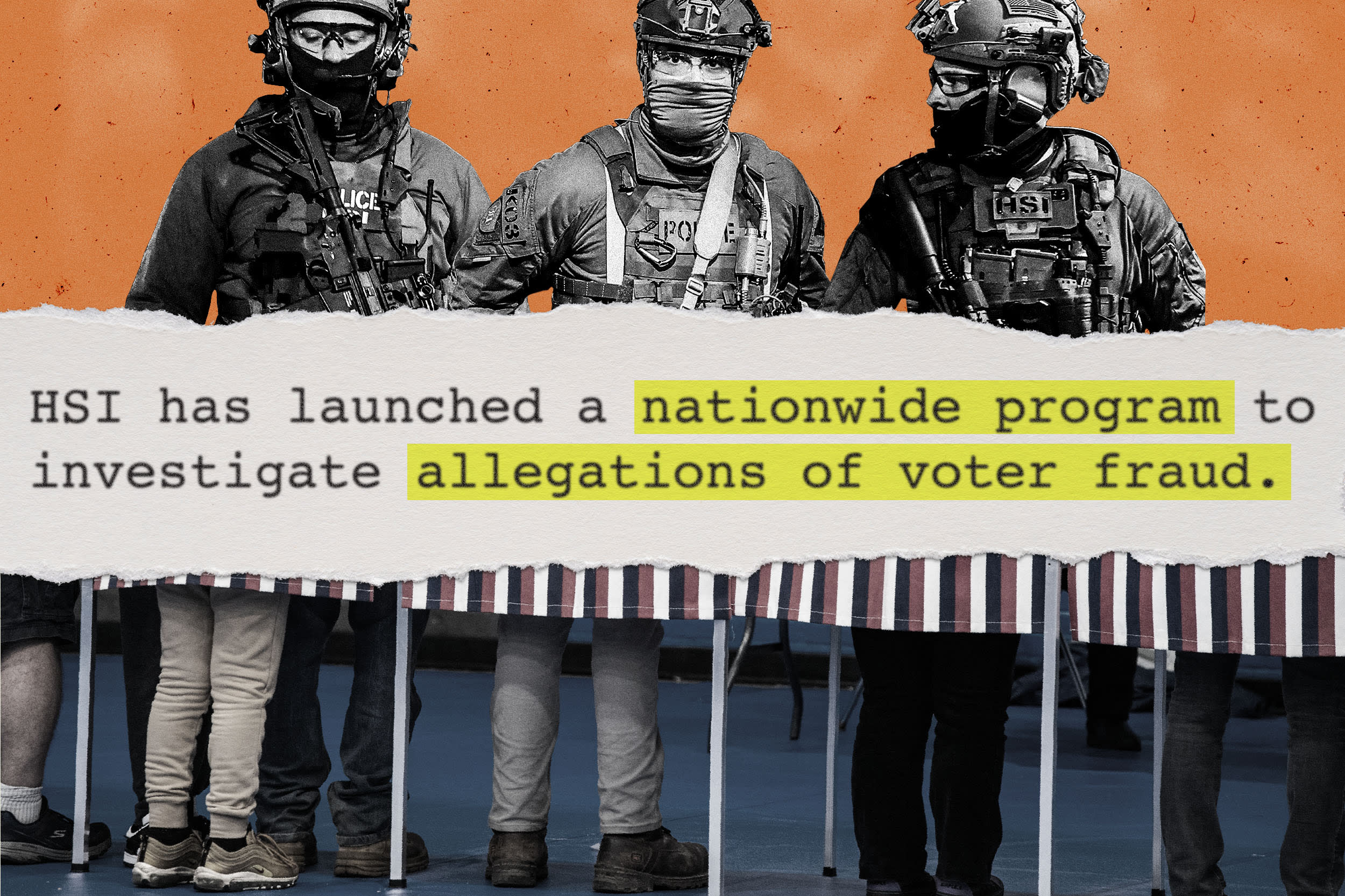

LAS VEGAS — An influential network of conservative activists fixated on the idea that former President Donald J. Trump won the 2020 election is working to recruit county sheriffs to investigate elections based on the false notion that voter fraud is widespread.

The push, which two right-wing sheriffs’ groups have already endorsed, seeks to lend law enforcement credibility to the false claims and has alarmed voting rights advocates. They warn that it could cause chaos in future elections and further weaken trust in an American voting system already battered by attacks from Mr. Trump and his allies.

One of the conservative sheriffs’ groups, Protect America Now, lists about 70 members, and the other, the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, does not list its membership but says it conducted trainings on various issues for about 300 of the nation’s roughly 3,000 sheriffs in recent years. It is unclear how many sheriffs will ultimately wade into election matters. Many aligned with the groups are from small, rural counties.

But at least three sheriffs involved in the effort — in Michigan, Kansas and Wisconsin — have already been carrying out their own investigations, clashing with election officials who warn that they are overstepping their authority and meddling in an area where they have little expertise.

“I’m absolutely sick of it,” said Pam Palmer, the clerk of Barry County, Mich., where the sheriff has carried out an investigation into the 2020 results for more than a year. “We didn’t do anything wrong, but they’ve cast a cloud over our entire county that makes people disbelieve in the accuracy of our ability to run an election.”

In recent years, sheriffs have usually taken a limited role in investigations of election crimes, which are typically handled by state agencies with input from local election officials. Republican-led state legislatures, at the same time, have pushed to impose harsher criminal penalties for voting infractions, passing 20 such laws in at least 14 states since the 2020 election.

“This is all part and parcel of returning to a world where we’re using the criminal law in a way to make voting harder,” said Sophia Lin Lakin, the interim co-director of the Voting Rights Project at the A.C.L.U. “All the things that used to feel more fringy no longer feel so fringy, as we’re starting to see this very much collective effort.”

The sheriff of Racine County in Wisconsin, the state’s fifth-most-populous county, is trying to charge state election officials with felonies for measures they took to facilitate safe voting in nursing homes during the pandemic.

In Barry County in Michigan, a rural area that voted overwhelmingly for Mr. Trump, the sheriff has been investigating the 2020 election after becoming involved with efforts by people working on Mr. Trump’s behalf to try to gain access to voting machines.

And the sheriff of Johnson County in Kansas, which includes suburbs of Kansas City and is the most populous county in the state, has said he is broadly investigating the county’s 2020 election. At a recent meeting with election officials, he questioned their procedures and integrity, according to a written account from the county’s top lawyer, who sent him a letter expressing concern that he was interfering in election matters.

The Johnson County sheriff, Calvin Hayden, said in an interview that sheriffs faced a learning curve.

“We don’t know anything about elections,” he said. “We’re cops. We have to educate ourselves on the system, which takes a long, long time.”

Hatching election plans in Las Vegas

The three sheriffs gathered with a few hundred others at a forum this month in Las Vegas hosted by the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association.

Attendees included leaders of True the Vote, a group whose work spreading discredited theories of mass voter fraud inspired the conspiratorial film “2000 Mules”; Mike Lindell, the Trump ally and MyPillow chief executive; and other prominent figures in the 2020 election-denial movement.

Speakers urged more sheriffs to open investigations of the 2020 election, which they compared to a rigged sporting event, presenting evidence that rehashed long-disproved theories. One speaker said the way that betting odds had changed on election night constituted proof of a stolen election.

Some of the arguments centered on the premise of “2000 Mules”: that an army of left-wing operatives wrongfully flooded drop boxes with absentee ballots in 2020. Many, including William P. Barr, Mr. Trump’s former attorney general and Georgia state officials, have pointed to major flaws in the supposed findings and the flimsy evidence presented.

Still, Richard Mack, the founder of the constitutional sheriffs association, said the accusations made in “2000 Mules,” which was released in May, were a “smoking gun” and had persuaded him to make election issues his group’s top priority.

Mr. Lindell said in an interview that he and his team had offered the three sheriffs “all of our resources,” including computer experts and data on voters, but that he had made no financial commitments.

The Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, which was formally founded about a decade ago by Mr. Mack, is dedicated to the theory that sheriffs are beholden only to the Constitution and serve as the ultimate authority in a county — above local, state and federal officials and statutes. The group, whose leaders have promoted Christian ideology in government, has been active in supporting fights against gun control laws, immigration laws and federal land management.

Protect America Now, founded by Sheriff Mark Lamb of Pinal County, Ariz., and Republican operatives, was announced shortly after the 2020 election. Its principles closely align with many of the constitutional sheriffs association’s, but it has employed more traditional political methods such as running ads.

Attempts to interview Mr. Lamb, who has not announced local investigations into election issues, were unsuccessful. Discussing his partnership with True the Vote at a Trump rally in Arizona on Friday, he said sheriffs would do more to hold people accountable for violating election laws. “We will not let happen what happened in 2020,” he said.

For conservative activists focused on voter fraud, an alliance with law enforcement seemed natural.

True the Vote initially approached state and federal law enforcement agencies with its election claims, but did not provide sufficient evidence to warrant an investigation, officials said.

In partnership with Protect America Now, the group has now raised $100,000 toward a goal of $1 million for grants to sheriffs for more video surveillance and a hotline to distribute citizen tips.

True the Vote’s executive director, Catherine Engelbrecht, said in a speech at the Las Vegas event that in sheriffs, she had found a receptive audience for her claims.

“It’s the sheriffs,” she said. “That’s who we can trust.”

A troubled history of law enforcement at the polls

Some conservative activists have also floated the idea of increasing the presence of sheriffs wherever ballots are cast, counted and transported, echoing a proposal by Mr. Trump in 2020 that didn’t gain steam.

Deputizing volunteers could even be an option, said Sam Bushman, the national operations director for the constitutional sheriffs association.

Jim Marchant, the Republican nominee for secretary of state of Nevada and an attendee in Las Vegas, said that if elected, he would try to “bring sheriffs back in” to the election process.

“The deputies are going to be there at the locations to watch for any anomaly,” he said in an interview.

For voting rights groups, the potential presence of law enforcement officers at polling locations evokes a darker period in American democracy, when the police were weaponized to suppress turnout by people of color.

Because of this history, state and federal protections limit what law enforcement can do. In California and Pennsylvania, for example, it is a crime for officers to show up at the polls if they have not been called by an election official. In other states, including Florida, North Carolina, Ohio and Wisconsin, officers must obey local election officials at the polls, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

Sheriffs interviewed at the Las Vegas event said they were aware of such restrictions and did not want to impede voting. The Barry County, Mich., sheriff, Dar Leaf, said he was more focused on 2020 rather than looking ahead. Others, like Mr. Hayden, said they were considering increased video surveillance of drop boxes.

Mr. Mack said, “I don’t think any sheriff is trying to intimidate people not to vote.”

Some sheriffs from rural Trump-voting counties said they hadn’t observed major problems to fix in their own counties but supported more sheriff involvement overall. Richard Vaughn, a sheriff in rural Grayson County in Virginia, said he wanted officers to be involved in observing vote counts, and would support election investigations “in areas where there are allegations.” “A lot of people are losing confidence,” he added.

Wide-ranging investigative scrutiny

Election experts say the activities of the three sheriffs already raise concerns.

Sheriff Hayden of Johnson County, Kan., said he had started investigating elections after receiving 200 citizen complaints.

He is scrutinizing “ballot stuffing,” “machines” and “all of the issues you hear of nationally,” he said in an interview. Asked what he meant by ballot stuffing, he described the practice of delivering absentee ballots on behalf of other voters. (During the 2020 election, Kansas did not have a law regarding that practice; last year, it passed legislation allowing people to return no more than 10 ballots from other voters.)

Mr. Hayden said in a statement that he disagreed with the county lawyer’s depiction of his meeting with election officials and that he was treating the elections work like any other investigation.

“Our citizens want to have, and deserve to have, confidence in their local elections,” he said.

Mr. Leaf has led an effort to try to investigate voting machines.

Emails obtained last year from his department by the news site Bridge Michigan showed that a lawyer identifying Mr. Leaf as his client had communicated about seizing machines with Trump allies who were trying to prove 2020 election conspiracy theories.

In December 2020, Mr. Leaf met with a cybersecurity specialist — who was part of the Trump allies’ network — to discuss voting machine concerns, Mr. Leaf said in an interview.

Mr. Leaf said he had also been provided with a private investigator for election matters by another lawyer of his, who previously helped Sidney Powell, a former lawyer for Mr. Trump, bring a conspiratorial lawsuit seeking to overturn Michigan’s 2020 results.

At one point, someone connected to Mr. Leaf’s investigation gained access to a voting tabulator, according to state police records. State authorities intervened and began investigating Mr. Leaf’s office.

Over 18 months, Mr. Leaf’s investigative efforts have changed focus several times, and he has had three search warrant requests rejected for lack of evidence, Julie A. Nakfoor Pratt, the county’s top prosecutor, said in an interview.

Mr. Leaf said in a statement, “I took an oath and obligation as sheriff to investigate all potential crimes reported to my office, including election law violations.”

In Wisconsin, Mr. Schmaling has tried to charge statewide election officials with violating the law by temporarily suspending election oversight work in nursing homes.

Those officials, who serve on the Wisconsin Elections Commission, the state’s bipartisan arbiter of election matters, voted for the suspension in March 2020, as the pandemic was first raging. After investigating a complaint in November 2021, Mr. Schmaling said he had found eight instances of potential fraud.

No fraud charges were filed in any of the cases.

But in November, Mr. Schmaling issued criminal referrals for five of the six members of the Wisconsin Elections Commission, recommending that the district attorneys in the counties where they live charge them with crimes including felonies.

Three of the district attorneys have dismissed the referrals; two have not yet made a decision.

Mr. Schmaling, who said his nursing home inquiry took up hundreds of hours, described his decisions as routine. “The bigger picture for me is we exposed something that was wrong, something illegal,” he said. “My goal is to make certain that the law is followed.”

But others involved said the actions were an overreach of power.

“The idea that the solution for an election whose results you didn’t like is, after the fact, to threaten criminal charges for that public work of a government official is shocking,” said Ann Jacobs, the Democratic chair of the Wisconsin Elections Commission, who faced a criminal referral. “It is chilling. It is the antithesis of how democracy works.”