Great Reset demands a new portfolio approach – Investors Chronicle

- Inflationary conditions are bad for old 60:40 strategy

- Dynamic asset allocation superior on a risk-adjusted basis

Journalists, you may have noticed, are prone to hyperbole. So are some historians: giving emotive descriptions to swathes of time was irresistible to Eric Hobsbawm, the Marxist author of Age of Extremes, a work that surveyed the period from the start of world war one to the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

That period was characterised by struggles between nationalism, imperialism, capitalism, fascism and communism. But extremism didn’t go away after the Cold War.

Within a decade of the Wall’s fall there had been ethno-nationalist wars in the Balkans, genocide in Rwanda and Wahhabi jihadism was on the rise – with devastating effects to be felt in the west a few years later.

Less deadly, but as disruptive in the day-to-day lives of billions of people, were the Asian financial crisis, dotcom crash, Enron collapse and, biggest of all, the global financial crisis. Most recently, threats to life and prosperity converged with the Sars-Cov-2 pandemic. All in all, the last 30 years are in many ways undeserving of the moniker “The Great Moderation”.

Yet throughout this turmoil, the world enjoyed a boom in supply. Globalisation meant standardisation, removal of tariffs and access to cheaper labour, seemingly weakening the old link between rapid growth and unsustainably high inflation.

Plentiful global output afforded policymakers in advanced countries the luxury of keeping interest rates low. Cheap imports, particularly from China, meant ample goods for the money to chase, so prices didn’t rise too fast.

Consumers and businesses gorged on cheap credit, although western inequality widened. In the United States, the wealthiest top 10 per cent have seen their share of national income rise from 34 per cent in 1980 to a current level of 45 per cent says the World Inequality Report 2022 (an initiative by economists such as Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty).

Inequality emerged in the corporate world, too. Some companies borrowed excessively and others hoarded cash (part of what former Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke labelled the ‘savings glut’) because the overall indebtedness of developed economies made businesses question the risk-to-reward profile of investment, even though the cost of capital was low.

While investment in the west was below what it needed to be, and had a knock-on effect on productivity, China became a true powerhouse. Recognising that investment opportunities were few in the west (capacity particularly could be outsourced and offshored), huge multinationals continued to save. Despite a period of prosperity for equity markets, the number of companies truly worth owning on western bourses narrowed and it is no surprise that quality shares saw a particular rise in prices.

Elevated valuations were sustainable, so long as central banks weren’t afraid of inflation. For as long as that was the case, there was always likely to be a cut in interest rates to support the stock market should macro conditions sour. This so-called ‘Fed put’ (borrowed from the parlance of options trading) was a boon for equity investors.

Is it time portfolios went back to the future?

But the world has changed, and ‘Great Moderation’ has given way to ‘Great Reset’. Portfolio strategies anchored to the experience of the last 30 years are out of kilter with the reality of inflationary pressures and the anticipated retrenchment from globalisation.

Financial risk warnings always stress the past is no guide to future performance. That’s true, although there is still value to the Churchillian adage that “the farther backward you can look, the farther forward you can see”. With a delta of rising inflation not seen for decades, strategic asset allocations should be informed by the last 50 years, not five.

An extended delve into history is possible consulting studies such as the Barclays Equity Gilt Study, now in its 67th edition, which looks at the long-run return of UK government bonds (gilts), UK equities (shares) and cash going back to 1899; as well as US Treasury bonds, shorter-term Treasury bills, and equities from 1925.

Taking the 1970s as our starting point, between the end of 1971 and end of 2021 UK equities would, assuming all dividends were reinvested, have made an annualised real rate of total return of 4.9 per cent. That’s after inflation calculated by Barclays’ own cost of living index. The figure for gilts, again assuming all coupons reinvested, is just under 3 per cent.

Therefore, a portfolio split 60:40 between UK-listed shares and gilts, would have achieved, on average, 4.14 per cent a year allowing for inflation.

There are, however, differences between decades. From the end of 1971 to the end of 1981, UK shares on average chalked a negative 2.4 per cent a year in real terms, with gilts losing 5.6 per cent. If inflation persists for years, investors who trust in the old 60:40 portfolio should be duly warned by this data.

Another lesson comes from the lost decade for equities after the dotcom crash. Between the end of 1999 and the end of 2009, the real rate of return on UK shares was on average -1.2 per cent annually. Fortunately, for balanced 60:40 portfolios, the fact that gilts made 2.6 per cent a year ensured a positive 0.32 per cent real return annually – despite another of the deepest bear markets in stock market history emerging due to the financial crisis.

Back then, the problem was a global credit event choking off demand in the economy. Today, as in the 1970s, the issue is energy and supply side shocks forcing up the price of essential items and constraining the utilisation of production capacity.

Central banks know that the policies of low interest rates and quantitative easing employed after 2008 would only make things worse now. The opposite must be done to head off inflation – but tightening policy causes pain for those households and businesses with unsecured short-term debts.

It’s also a problem for governments: the rising cost of borrowing makes it more important for countries like Italy to rein in their spending. That harsh reality formed at least part of the backdrop to the collapse of the coalition headed by former European central bank governor, Mario Draghi.

Normally recession puts an end to inflation as people have less money to keep bidding up the price of goods. But the war in Ukraine is keeping food and energy expensive. With supply of these core items restrained it is possible for inflation to persist even as economies contract.

In its mid-year review, Fidelity International maintained there is a 20 per cent likelihood of global stagflation over a 12-month horizon. Fidelity’s most likely scenario by far is a more straightforward recession. The probability assigned to this outcome was raised to 60 per cent, up from 35 per cent when the same analysis was made at the previous quarter end.

Asset allocation going forward

It all makes for some of the hardest investment conditions in living memory. Big asset allocators are shifting their outlooks frequently (see page xx) but what they’re grappling with most is the positive correlation between total returns on bonds and shares since November 2021.

The combined inflation and bear market situations are very bad for straightforward 60:40 portfolios, as the performance in the 1970s demonstrates. So how do investors diversify their risk away from shares and control the peak-to-trough drawdowns suffered in down legs of the bear market?

Holding more in cash is eminently sensible but, aside from the value erosion because of inflation, there is also the risk of missing out on the best early upside in a recovery.

Research by Dr Brian Jacobsen & Matthias Scheiber of Allspring Global Investments this year looked at the question of when to diversify differently. In instances when there was a flight to safety, perhaps for geopolitical reasons, their findings suggested government bonds could still offset equity falls, albeit by less than in the past. When the issue spooking markets is inflation, however, government bonds are much more likely to fall in price, too.

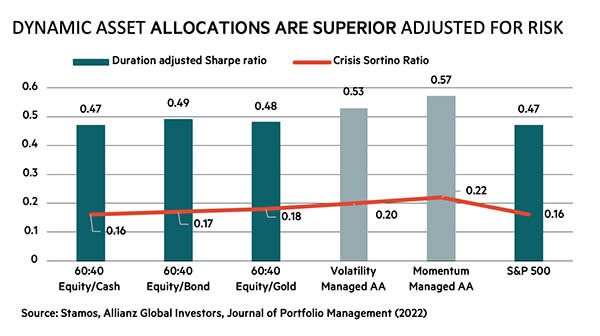

The question of how to diversify differently was also recently researched by Dr Michael Stamos, the director of multi-asset research at Allianz Global Investors. In a paper featured in the March 2022 edition of the Journal of Portfolio Management, Stamos examined the risk adjusted returns of several asset allocation techniques over the past 30 years.

Data covers only the Great Moderation period but, encouragingly, it highlights bond-free diversification with a risk-return that was comparable to 60:40 equity/bond allocations. Crucially, this was after adjusting for the arguably not repeatable duration premium (a bull market in bond prices fuelled by the suppression of real interest rates) that bonds earned over the past three decades.

This could mean investors have viable options to switch to when conditions are especially bad for bonds. The first metric Stamos used was an adjusted Sharpe ratio, which is the rate of return adjusted for duration minus the return from cash, then divided by volatility.

The second is a ‘crisis Sortino ratio’, which is the duration-adjusted return minus cash divided by ‘crisis volatility’ – ie, that seen if equities drop by more than 2 per cent. This was chosen because of the importance of a portfolio being able to reduce volatility on days with significant drawdown for shares.

Of the strategies tested, a simple 60 per cent shares and 40 per cent cash split, or going 60:40 shares to gold, produced a return very similar to those made by shares and bonds in the past. “In the current scenario, it is sensible to reduce bonds for gold or even cash to reduce duration risk, which may result in downside reduction similar to that delivered by bonds up to now,” Stamos wrote.

More difficult for ordinary investors to copy are the dynamic strategies such as managed momentum and managed volatility investing. Stamos’ dynamic momentum strategy, for example, has a minimum 30 per cent and a maximum 90 per cent in shares, with the rest in cash. The equity exposure is adjusted based on past 120-day stock market return. When the proportion of shares is cut, the reduction is proportionate to the size of past negative log returns.

Turnover costs can also be prohibitive when it comes to running momentum strategies, although this could perhaps be mitigated by trading exchange traded funds (ETFs) on a few core indices.

Managed volatility, in this instance defined as a situation where equity allocations (in a shares and cash portfolio) are inversely proportional to the trailing 60-day realised volatility of equities, could also require frequent adjustments. Again, the equity exposure is truncated between 30 and 90 per cent, and as with the momentum system, the adjusted Sharpe and Sortino ratios are evident of superior risk adjusted performance.

But whether investors are private or professional in nature, taken in sum these examples suggest there are relatively comforting asset allocation options available – ones that may be better suited to the Great Reset as bond markets face a period of prolonged readjustment.