Misinformation of COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy | Scientific Reports

Participants and procedure

To examine the influence of knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccines on vaccine hesitancy, a cross-sectional survey was designed. This online survey was opened for data collection for three months from February 2021 to May 2021 upon receiving an approval from the IRB at the University of Oklahoma. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations of the IRB. During that period of data collection, the COVID-19 vaccines had become available to the public in the United States. Respondents were recruited via convenience sampling from a departmental research pool (i.e., SONA) at the university. Students at the university who were taking courses from the department voluntarily signed up to join the research pool and they could select studies they wanted to participate in. A total of 597 responses were collected for the Study 2 and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Of them, 156 cases were excluded because of incomplete/missing information, leaving 441 responses available for the remaining analyses. Demographics of the participants (n = 441) are reported in Table 3.

To be eligible for this study, participants were required to be aged 18 years or older and to have not received a COVID-19 vaccine yet. Participants were also informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, risks and benefits, compensation, voluntary nature of the survey, and confidentiality. Those who consented to participate in this study signed the online informed consent and then were asked to complete the following parts. First, they completed demographic information including age, gender, ethnicity, religion, political party affiliation, and political ideology. Next, they answered questions assessing their knowledge levels about COVID-19 vaccines. Third, they answered questions asking about their hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccination, and finally, they estimated their behavioral intention to get a COVID-19 vaccine. At the end of the survey, we provided a comprehensive fact sheet about the COVID-19 vaccines. Participants received extra credit for their participation.

Measures

Knowledge about COVID-19 vaccines

To evaluate levels of knowledge (and possible misconceptions) about the COVID-19 vaccines, participants were presented with 10 statements (five true and five false) about the COVID-19 vaccines. An example of a true statement is “With most COVID-19 vaccines, you will need 2 shots to get the most protection” and for a false statement, “COVID-19 vaccines can cause autism”.

Participants were asked whether to the best of their knowledge these statements were true or false. The statements were provided based on the COVID-19 Vaccine Communication Handbook11 including widespread myths and anti-vaccination misinformation. The number of correctly answered statements was summed to assess knowledge levels of the COVID-19 vaccines (M = 8.35, SD = 1.87).

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy (VH)

The Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (VHS)28 was used to measure participants’ hesitancy levels to get vaccines in general. To reflect the focus of this study, we specified the items by replacing the word, “vaccines” with “COVID-19 vaccines”, and the word, “childhood” to “me”. For instance, we modified the statement “Childhood vaccines are important for my child’s health” to “COVID-19 vaccines are important for my health”. The VHS includes nine items including seven reversed items in the scoring of the scale (e.g., “COVID-19 vaccines are effective”, and “Getting a COVID-19 vaccine is a good way to protect me from disease”). They were measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). As a result of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), two items (i.e., item 5 and item 9) were excluded due to lower factor loadings (less than 0.4)30. The modified scale was valid to conduct further analyses: χ2(14) = 44.93, p < 0.001, χ2/df = 3.21, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.07, and SRMR = 0.02. The items were averaged with higher scores indicating more hesitancy to get a COVID-19 vaccine (M = 2.71, SD = 0.93).

Behavioral intention (BI) for COVID-19 vaccination

Based on Rothman et al.’s measurement31, the behavioral intention to get a COVID-19 vaccine was assessed with two items such as (a) if you were faced with the decision of whether to get the COVID-19 vaccine today, how likely is it that you would choose to get vaccinated? and (b) how likely would you be able to get the COVID-19 vaccine in the future? These items were measured with a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely). Higher scores on this variable indicate greater intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine in the future (M = 3.30, SD = 1.36) (see supplementary information).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis, and intercorrelations of knowledge levels about COVID-19 vaccines, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, and behavioral intention to get COVID-19 vaccines are indicated in Table 4. The percentage of true and false responses is indicated in Table 5. The total of COVID-19 vaccine knowledge scores ranged from 2 (6 respondents) to 10 (154 respondents), with a mean of 8.35 (SD = 1.87).

Descriptive and correlation analyses were conducted to confirm the normality of the data and to explore the participants’ demographic characteristics and the relationships among all the variables of this study using SPSS 26.0. Before conducting SEM, reliabilities and validities of the measurements were tested. We found that the measurements of this study had robust internal reliabilities as well as convergent and discriminant validities: the Cronbach’s α values were all above 0.80, and the factor loadings of the items of each construct, composite reliabilities (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were over 0.60, 0.80, and 0.60, respectively. The outcomes fulfilled the criterion of reliabilities and validities for all the constructs (see Table 6).

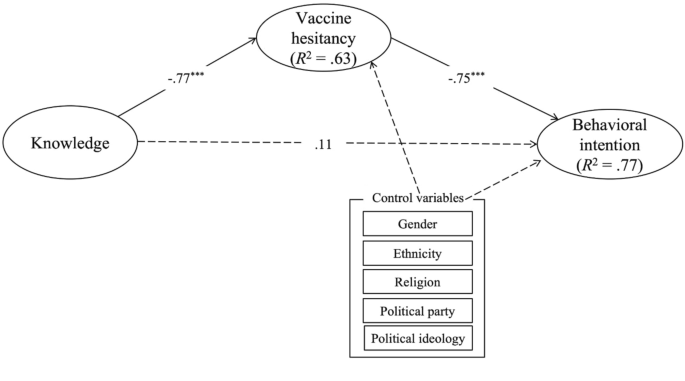

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was also performed to examine the measurement model and hypotheses of this study using AMOS 25.0. Maximum likelihood estimation was used to estimate the hypothesized model. To measure the overall fit of the suggested model, the following indices were used30: χ2/df < 3, the comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.90, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.07, and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) < 0.08. To test the mediating effect of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, bootstrapping was applied with 2000 bootstrapped replications and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All the estimates were indicated in standardized scores. We controlled gender, ethnicity, religion, political party affiliations, and political ideology as they have been significantly related to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and behavioral intentions to get the vaccines32,33,34,35.