Trump’s ‘Big Lie’ May Have Influenced Voters in Georgia Runoff – News @ Northeastern

How did former president Donald Trump’s false claims of voter fraud in Georgia during the 2020 general election impact the state’s subsequent Senate runoff election? Might it actually have tipped the scale in favor of Democratic challengers Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock?

It’s a question that political scientists have been asking in the aftermath of the runoff that handed the Democrats a thin majority of seats in the Senate. And while it’s difficult to measure the effects that such claims have on voting behavior, researchers at Northeastern were able to show in a new paper that there were at least modest links between Trump’s “big lie” and how Georgians cast their vote in the crucial contest.

The study, published Tuesday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), looked to examine, broadly speaking, whether “public endorsements of conspiracy theories are associated with real-world voting behavior.”

“In this, we test whether Georgia citizens who publicly endorsed or rejected conspiratorial content on Twitter prior to that state’s Senate runoff election turned out in that election at different rates than similarly situated Twitter users in Georgia who did not,” the authors wrote.

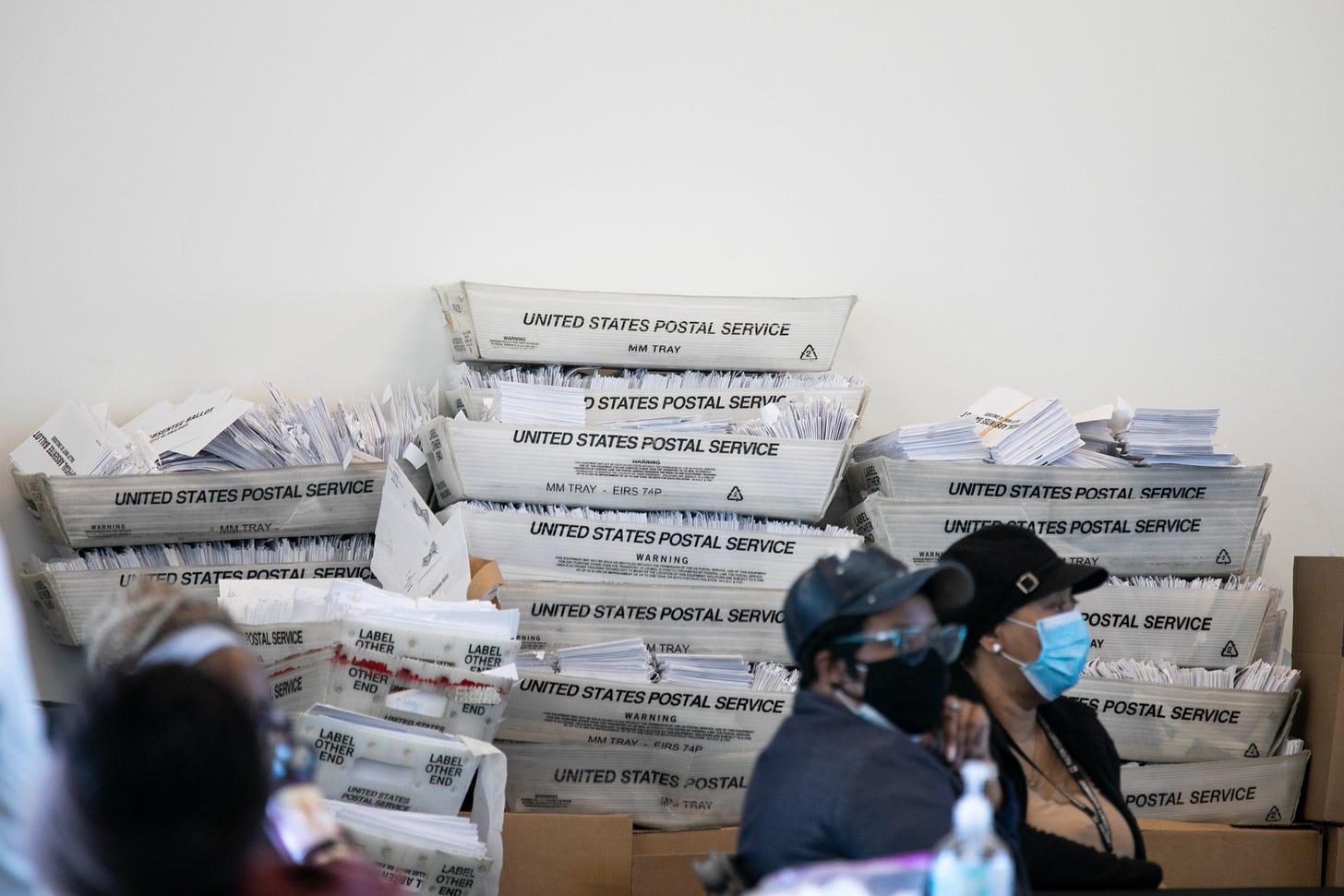

Researchers analyzed the social media posts from roughly 45,000 Georgia voters, which they cross-referenced with a digital voter identification database. What they found was that those voters whose Twitter posts promoted Trump’s conspiracy theories about the 2020 election turned out in fewer numbers than those voters whose posts expressed the opposite sentiment.

Specifically, the researchers found that “liking or sharing messages” opposed to the conspiracy theories was linked to higher-than-normal turnout at the polls. Those who liked or shared tweets that endorsed Trump’s falsehoods, on the other hand, were less likely to vote.

On their own, the results don’t definitively prove that belief in Trump’s election theft conspiracy actually deterred his base from voting (because believing it, it is reasoned in the paper, might lead adherents to think they couldn’t affect the outcome of a “rigged” election). Nor does it suggest that such bold lies galvanized Democrats to turn out in greater numbers.

Ahead of their findings, the researchers laid out other theories to explain how voters might respond to conspiracy theories about the election. Voters who bought into the conspiracy claims may have thought that Republican incumbents David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler—in lending credence to the potential Democratic “trifecta” in the House, Senate and presidency (therefore, Joe Biden’s victory)—weren’t demonstrating “sufficient commitment to … Trump” and his claims of conspiracy and, therefore, were not worth supporting.

“However, election conspiracy theories could also encourage participation in subsequent elections by stoking political anger, directing adherents to continue democratic participation as a means of rectifying political opponents’ previous malfeasance,” the authors wrote.

The results of the study provide a foundation to analyze the voting behavior during the midterms and future elections, as more candidates embrace election disinformation as political strategy, says David Lazer, university distinguished professor of political science and computer science, and co-author of the research.

“The lesson we cannot quite draw is that pushing conspiracy theories will suppress turnout; but it does suggest caution [in deploying conspiracies] as a political strategy,” Lazer says. “This is very important to explore, because conspiracy theories around whether votes are being counted or miscounted in elections are now firmly ensconced in the American psyche.”

Lazer says the U.S. experiences “cyclical bouts of paranoia” in its electoral politics, but warns that Trump’s “big lie” represents a dangerous slide away from democratic norms.

“In the absence of meaningful consequences … this is an option that’s just on the table now for candidates,” says Jonathan Green, a senior research scientist at the Lazer Lab, the research outfit that conducted the study.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu