Files copied from voting systems were shared with Trump supporters, election deniers

Plaintiffs in a long-running federal lawsuit over the security of Georgia’s voting systems obtained the new records from the company, Atlanta-based SullivanStrickler, under a subpoena to one of its executives. The records include contracts between the firm and the Trump-allied attorneys, notably Sidney Powell. The data files are described as copies of components from election systems in Coffee County, Ga., and Antrim County, Mich.

A series of data leaks and alleged breaches of local elections offices since 2020 has prompted criminal investigations and fueled concerns among some security experts that public disclosure of information collected from voting systems could be exploited by hackers and other people seeking to manipulate future elections.

Access to U.S. voting system software and other components is tightly regulated, and the government classifies those systems as “critical infrastructure.” The new batch of records shows for the first time how the files copied from election systems were distributed to people in multiple states.

Marilyn Marks, executive director of the nonprofit Coalition for Good Governance, which is one of the plaintiffs in the Georgia lawsuit, said the records appeared to show the files were handled recklessly. “The implications go far beyond Coffee County or Georgia,” Marks said.

In a statement to The Post, SullivanStrickler said the attorneys who hired the firm directed it “to contact county officials to obtain access to certain data” from Dominion Voting Systems machines in Georgia and Michigan.

“Likewise, the firm was directed by attorneys to distribute that data to certain individuals,” the statement said. The firm said that it “had [and has] no reason to believe that, as officers of the court, these attorneys would ask or direct SullivanStrickler to do anything either improper or illegal.”

Dominion Voting Systems has been the target of baseless claims from Trump, his advisers and allied news organizations that its machines were hacked and were programmed to flip votes from one candidate to another. The Colorado-based company has filed a host of defamation lawsuits over the statements.

Dominion declined to comment on ongoing investigations but in a statement said: “What is important is that nearly two years after the 2020 election, no credible evidence has ever been presented to any court or authority that voting machines did anything other than count votes accurately and reliably in all states.”

The Post reported on Aug. 15 that an earlier set of records released in response to the subpoena showed SullivanStrickler was hired in late November 2020 to conduct a multistate effort to copy software and other data from county election systems. The effort was more successful than previously known, accessing equipment in Georgia, Michigan and Nevada.

That same day, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) opened “a computer trespass investigation” regarding an elections server in Coffee County, bureau spokeswoman Nelly Miles said. Under Georgia law, knowingly using a computer or network without authority and with the intention of deleting, altering or interfering with programs or data is computer trespass, a felony.

SullivanStrickler’s statement said the firm would be “fully cooperative” with investigators. “We are confident that it will quickly become apparent that we did nothing wrong and were operating in good faith at all times,” it said.

The new documents were disclosed after plaintiffs asked the forensics firm who had accessed the Georgia elections data that the firm had collected, according to two people familiar with the case, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the litigation. The plaintiffs also received copies of the raw elections systems data collected by SullivanStrickler in Georgia, but those were not among records reviewed by The Post.

The new records also inadvertently detailed the sharing of data the firm collected during a separate forensic examination in Antrim County, where a judge in December 2020 had granted access to elections systems in response to a lawsuit challenging the 2020 results. The lawsuit was eventually dismissed.

In the records turned over to the Georgia plaintiffs, some pages, and portions of others, were blacked out. However, the text beneath some of the blacked-out blocks became visible when a Post reporter copied and pasted it into a separate file, showing downloads of files labeled “Antrim.”

In Georgia, Gabriel Sterling, the interim chief of staff in the Secretary of State’s office, told The Post in a statement that wrongdoers would be prosecuted. The secretary is a defendant in the litigation that uncovered the new records. Miles, the GBI spokeswoman, said in emails that Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger’s office on Aug. 2 had asked the agency to join efforts to examine the alleged Coffee County breach.

“Any attempts to illegally access election systems in Georgia will not be tolerated — whether it is rogue election officials, conspiracy-theorist attorneys, or security consultants working for those conspiracy theorists,” Sterling said.

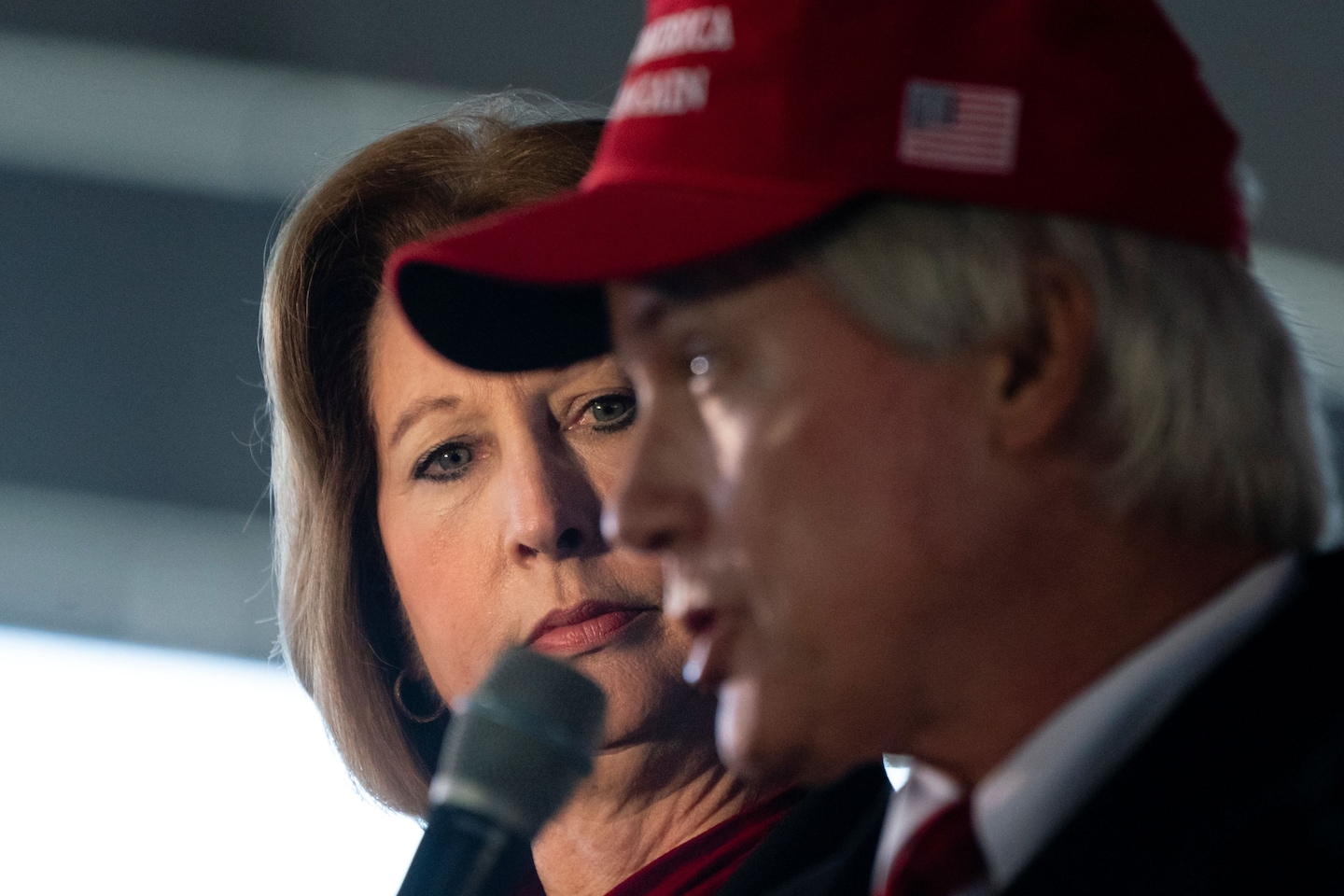

The records show that 10 people downloaded data collected from Georgia or Michigan between December 2020 and February 2021. They also show in more detail the role of Powell, the attorney who pushed false claims about voting machines in a flurry of swing-state lawsuits for Trump, as well as the role of Jesse Binnall, an outside counsel to the Trump campaign. Powell and Binnall signed engagement agreements authorizing SullivanStrickler to carry out “computer forensic collections,” the documents show.

A 16-page agreement signed by Binnall on Nov. 30, 2020, stated it covered data collection in Nevada, where Binnall had won a court order granting limited access to equipment, and in Georgia. The agreement said Binnall would pay SullivanStrickler $19,500 per day for a team of three people to work in Nevada, and listed potential fees for work in Georgia.

Powell did not respond to requests for comment. The newly released records do not show Binnall in discussions about Coffee County.

A legal adviser to the Trump campaign, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive matters, said the campaign had not intended to contract the firm in Georgia. “To the extent Georgia was ever mentioned in the agreement, it was an error in wording that was missed because of substantial time pressure,” the person said.

A visit to rural Georgia

SullivanStrickler investigators ultimately copied data from elections systems in Coffee County offices on Jan. 7, 2021, the records show. A senior executive from the firm, Paul Maggio, updated Powell by email on their progress. The firm billed Powell $26,000 for a day’s work by four people.

SullivanStrickler sent its statement after The Post emailed Maggio seeking comment.

Misty Hampton, then a local elections supervisor, allowed the group into the Coffee offices so they could prove the “election was not done true and correct,” she previously told The Post. Hampton resigned under pressure last year because she falsified time sheets, according to county officials.

Maggio began uploading the Coffee County data to the company’s file-sharing server on Jan. 9, according to the records. One record appeared to list accounts that were granted access to the server and whether they had permissions to download, upload or delete files.

During the following weeks, the records show, files named in part “Coffee County” were downloaded by accounts in the names of at least four people outside the firm: Jim Penrose, a cybersecurity consultant who has said he formerly worked for the National Security Agency; Doug Logan, whose firm CyberNinjas conducted a Republican election review in Arizona; Conan Hayes, a former pro surfer from Hawaii; and a fourth person identified as “Scott T.”

Hayes and “Scott T” were listed in the company records as working for ASOG, short for Allied Security Operations Group. The Post previously reported how the Addison, Tex.-based firm rose from obscurity to produce a report on Antrim County that, although discredited, was circulated among senior administration officials and cited by Trump as proof the 2020 election was stolen.

A Twitter account used by Hayes has posted conspiracy theory material and images purportedly of Dominion voting systems in Michigan. In an affidavit first reported by the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel, an investigator for the district attorney in Mesa County, Colo., alleged that Hayes worked with local officials there to copy elections software in May 2021. Three local officials were indicted on felony charges over the alleged breach. No charges were filed against Hayes.

Penrose, Logan and Hayes did not respond to requests for comment.

Kevin Skoglund, a cybersecurity expert working for plaintiffs in the Georgia lawsuit, told The Post that copies of elections software and other data like those collected by SullivanStrickler in Coffee County could aid people trying to compromise machines that use similar systems.

“We can’t know how many copies exist or who has them,” Skoglund said. “Someone might distribute it willingly or just fail to keep their copy safe.”

Downloads of data from Antrim

SullivanStrickler’s work in Michigan began after Republican lawyer Matthew DePerno, who had filed the election challenge lawsuit in Antrim County, won a Dec. 4, 2020, court order granting access to the county’s elections systems. Antrim was under scrutiny after initially reporting inaccurate vote tallies that showed Joe Biden beating Trump in a Republican stronghold. DePerno is now the Trump-endorsed Republican nominee for Michigan attorney general.

The judge in the lawsuit, Kevin A. Elsenheimer, issued a protective order “restricting use, distribution or manipulation of the forensic images and/or other information gleaned from the forensic investigation” without further authorization from the court.

A Dec. 6, 2020, engagement agreement signed by Powell said SullivanStrickler would be paid $26,000 per day for work in Michigan by a team of four. It also said the firm would be paid the same rate for work in Arizona, but did not elaborate. That day, the firm made copies from elections equipment in Antrim’s county offices.

Over the following week, two SullivanStrickler employees who worked on the Antrim examination uploaded dozens of files to a folder named “Forensic Images,” the company records show. This folder was stored within another folder, whose name was the project number cited by the firm in emails about elections work. Some of these files were shared with attorneys representing Antrim and Michigan’s attorney general in the lawsuit.

On Dec. 15, Elsenheimer lifted his protective order, ruling that DePerno’s team could release a redacted version of ASOG’s report on Antrim and distribute the findings of the forensic examination “as they see fit.”

After that, the SullivanStrickler records show, Antrim files were downloaded by accounts that the records say belonged to people including John Basham, a Texas-based meteorologist who has pushed false claims about the election on social media; former Michigan state senator Patrick Colbeck, who has promoted conspiracy theories about election fraud and other topics; and “Joe Ottman,” an apparent misspelling of right-wing podcaster Joe Oltmann, who has called for gallows to be built to “take care of all these traitors to our nation.”

The account the records tied to Basham began downloading dozens of files, some labeled “election management server,” in late December. The account that records tie to Colbeck downloaded six files from the same folder on Jan. 5, 2021, according to the records, including files labeled “election management server” and “ThumbDrives.” Colbeck in a film about the election released last year said that he had asked DePerno to take on the lawsuit there.

The “Joe Ottman” account downloaded two files on Jan. 6, according to the records. The email address associated with this account was Oltmann’s, according to filings in a separate court case. Oltmann wrote in a Jan. 6 email filed to that case that he was “sitting with Matt DePerno” and intended to publish “raw data from Antrim County machines.”

During a Jan. 11 hearing in the Antrim case, an attorney for Michigan’s attorney general raised concerns that forensic images from Antrim’s systems had been published online.

DePerno noted that there was no longer any protective order shielding these files.

Elsenheimer stated that anything not included in ASOG’s report was “still subject to” a protective order, a transcript shows. Elsenheimer said DePerno could share Antrim’s forensic images with his expert witnesses — a group that ultimately included Logan, Hayes and Penrose — but that “mass distribution” was not permitted, according to the transcript.

The SullivanStrickler records show that downloads continued. On Jan. 16, an account in the name of Michal Pospieszalski, author of the book “How To Talk To Hot Women,” downloaded a file from the Antrim folder. On Jan. 19, the same account downloaded another folder, which contained multiple files labeled “AntrimEMS” and others relating to Coffee County. A profile for Pospieszalski on a pickup artists website describes him as a “former hacker,” and his online résumé states that he worked between 2005 and 2006 as chief technology officer of the Election Science Institute, a now-defunct voter integrity group.

Steven Hertzberg, the group’s director at the time, told The Post he did not recognize Pospieszalski’s name but that he “did employ a white hat hacker around that time” who matched Pospieszalski’s physical description. Pospieszalski is also president of Matter Voting, a company that is developing voting systems based on blockchain technology also used in cryptocurrency, according to the firm’s website.

Basham also downloaded multiple “election management server” files from the same folder between Jan. 27 and Jan. 29, and then again on Feb. 11 and Feb. 12, according to the records.

In emails to The Post, DePerno said he had complied with the judge’s rulings.

“No order prohibited access to the forensic images at any time after December 15, 2020,” DePerno wrote in an email. “If the files were shared with people who were not experts it was not a breech of any order.”

When forensic images from Antrim’s systems were later widely shared during a “symposium” held in South Dakota in August 2021 by MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell, DePerno emailed Lindell a cease and desist demand, court records show. “Those images are under protective order,” DePerno told Lindell.

DePerno did not respond to a question about when the protective order he cited to Lindell came into effect.

Asked if he had requested access for Oltmann, Basham, Pospieszalski and Colbeck, DePerno said he did not recall who did so and does not know Pospieszalski. About Oltmann, DePerno said in an email: “If SullivanStrickler gave him access then he had every right to have the images.”

Basham said in an email that based on his reading of The Post, “I Do Not Expect Anything I Say To Be Represented Honestly.” Pospieszalski said in a message to The Post that he “can’t comment on what I did or did not find as part of my retained work for the Antrim county legal team as I’m under NDA,” a nondisclosure agreement. He characterized his eight years as a seduction and pickup coach as a “giant detour” from a career mostly focused on computer security.

Colbeck and Oltmann did not respond to requests for comment.

Data security expert Harri Hursti said in a court filing after the Lindell symposium that widespread release of server images “lowers the barrier to planning an attack against any election management system running this Dominion software.”

Alice Crites contributed to this report