How a retired MI6 boss, his Brexiteer friends and a celebrity Marxist became targets in Russia’s war on Ukraine

Press play to listen to this article

LONDON — In the disinformation drive around the war in Ukraine, even eccentric academics lunching with their grandsons can become collateral damage.

At first glance, Gwythian Prins, a professor at the London School of Economics, seems an unlikely target for Russian hackers seeking to discredit the British government. Yet the faceless hackers who broke into and published Prins’ personal emails revealed not only harmless discussions of his day-to-day life — including family lunches in rural England — but also extraordinary claims about an establishment plot to control the British government.

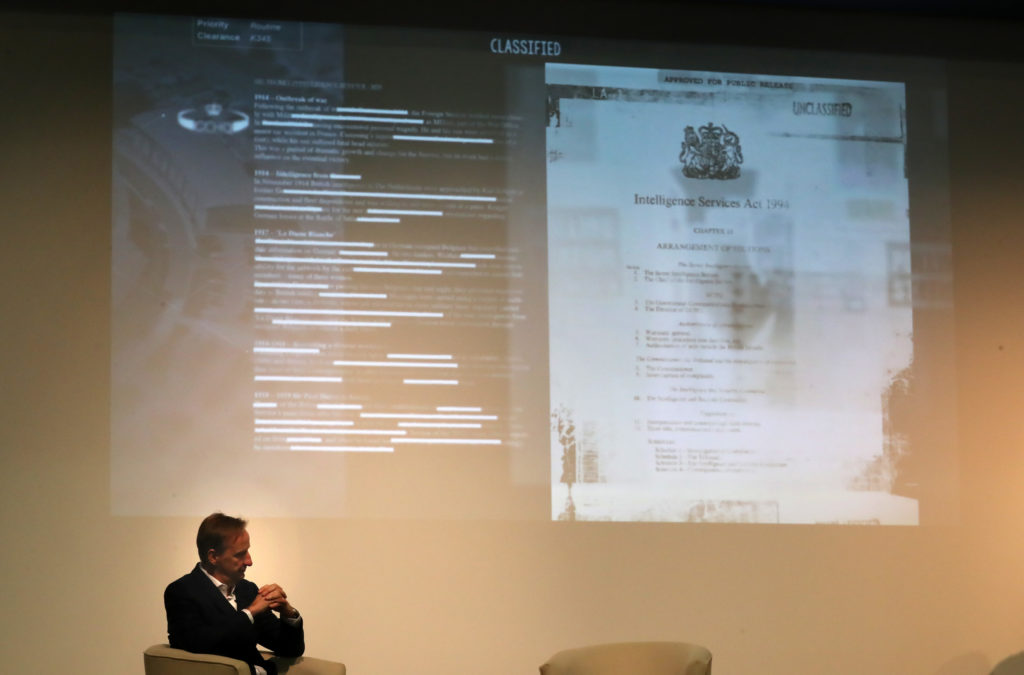

The hackers’ real target, it seems, was Prins’ retired friend and supposed co-conspirator, Richard Dearlove, with whom he frequently exchanged encrypted emails. Dearlove, an ardent Brexiteer, is a former boss of MI6, the top British spy agency made famous by the James Bond movie franchise.

Further attacks on prominent British political figures have followed. Suspected Russian hackers also targeted the Marxist activist Paul Mason, a former economics journalist on British TV news, and now a well-known political commentator who has urged fellow left-wingers to back British efforts to face down Russian President Vladimir Putin.

You may like

Both hacks are now subject to intensive investigations by the British security services, POLITICO can reveal.

And both targets — though on opposite ends of the political spectrum — have one thing in common: Their personal emails swiftly appeared on fringe far-left websites, alongside forcefully-written narratives attacking the victims’ motives but bearing questionable relation to the actual contents of the emails. These claims were then noisily amplified across like-minded corners of the internet, damaging the reputations of all involved.

“We’ve seen the Russian playbook enough times to know what it looks like — and this is it,” said one person caught up in the hacks. “It’s low-tech, but it’s sophisticated.”

Ross Burley, co-founder of the Centre for Information Resilience, explained: “Each day, the Kremlin and actors linked to it use disinformation, cyber attacks and propaganda to confuse and disrupt. No one is immune from the threat.”

He added: “They are constantly adapting new techniques and channels to target journalists, politicians, government officials, academics and civil society actors with a variety of influence operations — including so-called ‘hack and leak’ operations.”

Picking targets

Experts warn that state-linked hackers, or even freelancers who sell their illegally-obtained wares to higher powers, frequently stalk LinkedIn and other social networks with fake profiles to figure out who is talking privately to whom, before launching attacks on multiple targets within groups of friends or colleagues.

In the case of the Brexiteers, the outspoken Professor Prins appeared a good bet.

A passionate pro-Brexit thinker, boasting contacts both inside the U.K. government and among hardline backbench Conservative MPs during the Brexit battles in the wake of the 2016 referendum, Prins was sure to have a colorful inbox.

Prins is an unusual figure in the academic world. He has written articles for Net Zero Watch, a fringe campaign group that boasts the famously climate-skeptic former chancellor, Nigel Lawson, as a board member. He has also peddled unsubstantiated claims that Putin could have Parkinson’s disease.

Private emails he sent at the height of Britain’s Brexit drama in 2018 and 2019 were first published in April 2022, a few weeks after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, on a tailor-made pop-up website. As you’d expect, the emails are full of humdrum references to his home life — trips out with his grandson, a concert in rural Herefordshire, his exercise regime. Such private details are now public property, thanks to hackers clearly seeking a grander target.

The leaks website, named “Sneaky Strawhead” in an apparent attempt to link the emails to Britain’s blonde-haired prime minister, Boris Johnson, also claimed the messages contained sensational proof that “coup plotters” now ran the U.K. government. The website alleged that ex-MI6 chief Dearlove “together with his former colleagues and CIA cronies conducted [a] successful intelligence operation against No. 10.” The implication was that Johnson — Ukraine’s closest ally since the invasion — had been installed as prime minister following a secret plot by the elderly Brexiteers.

In fact, the emails reveal no such thing.

What is undoubtedly clear from reviewing the scores of leaked messages is that Prins and others in their network were indeed discussing ways to secretly discredit then-Prime Minister Theresa May at the height of the struggle over Brexit.

Prins and his pen pals were frustrated that the Brexit deal May was negotiating would have left Britain closer to the EU than alternatives pushed by Euroskeptics, and were desperate to influence the process before it was too late. But taken together, they reveal little more than a group of well-connected but hapless senior citizens proposing outlandish ideas, while lacking the levers to bring about change.

‘Maximum intelligence’

Somewhat incredibly, the emails include talk of retired MI6 boss Dearlove commissioning research operations against the most senior British officials involved in the negotiations. Dearlove complains about the “mafia of disloyal civil servants (cardinals of the old church)” overseeing the Brexit talks — but in the end, the chatter comes to nothing, after the former spook reports his sources have no valuable intelligence.

Elsewhere, Prins claims that Dearlove wants to get the “maximum intelligence” on anti-Brexit campaign group Best for Britain “and their co-conspirators.” He enthuses about suggestions Dearlove could even get former CIA colleagues involved. “He says that the people he has in mind are highly expert at this sort of espionage,” Prins tells an associate, excitedly. Again, the proposal appears to come to nothing.

There is also excitement around a set of supposed leaked notes of an alleged conversation between May and then-German Chancellor Angela Merkel, suggesting the British side ultimately hoped to return to the 27-nation bloc.

“Is this maskirovka [a term for Russian military disinformation]? Is it genuine? Is it fake kompromat?” Prins asks his friends, and briefly mulls using the document to hold the prime minister to ransom, signing off his email with a flourish: “Yours bloodthirstily.” But the group soon decide the so-called leak was indeed “poisoned bait for us to eat.”

Indeed, at times Prins appears to be seeking a conspiratorial coup even more shocking than the overblown writeup of his operation suggests. Yet in the end, the group is powerless, and their exchanges are laced with paranoia. At one point, Prins even questions whether Dearlove, the former intelligence boss, can be trusted as “one of us.”

Prins declined to speak to POLITICO. Dearlove could not be reached, although has published an article in the Spectator confirming the hack was genuine.

From rogue site to hard-left debating circles

After weeks of sitting on the internet, the cache of Brexiteer emails was picked up by fringe website the Grayzone, which promises “original investigative journalism” on “politics and empire” and has earned praise from Hollywood director Oliver Stone, famous for his interest in — and occasional embrace of — conspiracy theories.

The Grayzone has a reputation for pushing stories that match some of the narratives of Kremlin propaganda, as well as the propaganda of authoritarian regimes such as China and Syria.

The leak was written up by Kit Klarenberg, a British-born reporter working in Serbia, who has credits on Kremlin-controlled sites Russia Today and Sputnik, among others. His article sought to amplify the significance of what had been uncovered. “These efforts could amount to charges of TREASON,” he wrote.

“I do have a rather dramatic way of writing, I suppose, but I’ve certainly not consciously set out to exaggerate the significance of this,” Klarenberg told POLITICO in a phone interview.

He argued that the Brexiteer group was undoubtedly discussing how to undermine a democratic process through “subversive” means, and that even if the plans came to nothing, the actors involved do hold influence in government. He also suggested the leak shone an important light on how Westminster pressure tactics can actually work.

“To someone like yourself, who’s been writing about politics from the inside — in the Westminster village or whatever you want to call it — this is probably very normal,” Klarenberg said. “To the average person, this is quite sociopathic, actually.”

Dearlove’s take, as told to the Spectator, is very different. “A number of citizens, concerned that the Brexit vote of 2016 was being subverted, met in a pub to see whether they could do something about it,” he wrote. “You might think this was a perfect example of grassroots democracy — except that nothing came of it, and the little group never met again.”

The experience, he added, has been unsettling for friends who saw their private lives and messages published online. “Given my professional formation, I am not particularly phased by this sort of thing,” Dearlove wrote. “But for others involved it was both a novelty and provoked a mixture of anger, worry and farce. One told me it felt like being in a real-life Ealing comedy” — a reference to the much-loved farcical British movies of the 1940s and 50s.

Campaign against Mason

The leaks to Klarenberg did not end there.

Since the start of June, the Grayzone has published a string of his articles based on leaked emails from former Channel 4 journalist Mason, and those around him. The pieces appear intent on discrediting Mason, suggesting he is a propaganda mouthpiece for the British secret services.

The site highlights Mason’s efforts to fight pro-Russia narratives online, among academics and on the far left. It cites his private communications with an official working on disinformation in the U.K. Foreign Office as evidence of a nefarious plot.

“Are his activities influenced by shadowy state actors?” Klarenberg asked readers of Mason in June. A later Grayzone article questioned whether an attempt by Mason to become a member of parliament was “part of a U.K. intelligence operation to destroy the anti-war left,” given his past contact with the Foreign Office. Mason has refused to comment on the content of the emails, which he said “may be altered or faked,” and warned that “Grayzone’s publication has the effect of assisting a Russian state-backed hack-and-leak disinformation campaign.”

Some who have studied the Mason hack argue the motive was to paint all left-wing opposition to the invasion of Ukraine as an establishment stitch-up. Mason has vocally supported sending British arms to Ukraine to help its defense against Russia — a controversial view among some on the far left.

“The circumstances of the attack suggest it is highly likely that a Russian state or state-backed unit carried out the attack,” Mason wrote in a personal blog. He declined to comment when approached by POLITICO.

Wartime propaganda

Indeed, the working assumption among those who have studied both hacks is that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine provides the underlying motivation for the entire operation, seeking to undermine figures across the British landscape who have spoken out against Putin.

“In targeting Dearlove, what [the hackers] were trying to do was destabilize Boris Johnson,” said one observer who has studied the hack-and-leak tactics. “It was about suggesting he was brought to power by a bunch of former spooks in a coup.”

“Some of our Brexiteers have been quite outspoken in defending Ukraine and criticizing Russian aggression,” Dearlove noted in his article following the hack.

Experts assume both hacks were classic phishing scams — and point to a hacking outfit named Cold River, which has worked against firms operating in the Middle East and ramped up its work since the Ukraine invasion.

Also known as Callisto and the Reuse Team, the group has targeted U.S. think tanks, NATO offices and militaries in Eastern European nations, according to Google hacking experts and other tech assessors.

The group is thought to use “credential harvesting” plants in emails and online documents, which trick people into submitting usernames and passwords on sites that appear genuine, according to an assessment POLITICO has seen. In both the U.K. cases, ProtonMail inboxes were hacked — despite the email provider’s reputation for security.

“Expert examination, since confirmed by Google’s security teams, indicates that this was not some spare-bedroom hacker, but an operation so sophisticated that it could only have been done by a state actor,” wrote Dearlove.

Once the content is obtained, it is shared by foreign sites and on social media platforms like Telegram, before ending up on custom-made U.K.-focused sites, or handed to blogs known for spinning source material through an anti-Western prism.

Klarenberg said the leaks came to him via burner email accounts.

His position is that the origin of the material is irrelevant, so long as it is real. “If the material is factually accurate, then irrespective of the source, I think it should be published,” he argued, insisting both stories contained enough red flags to be newsworthy.

He also dismissed the focus on whether the leaks were linked to the Kremlin. “If the CIA hacks Chinese, Russian or Iranian government computers, and then releases the content, do journalists sit there thinking — ‘this is coming from an agency that has been engaged in all manner of morally reprehensible skulduggery all over the world for decades?’” he asked.

“I don’t think journalists in the Western world have those kinds of considerations.”

‘The threat will only increase’

Efforts to counter hacking and its fallout are now an industrial-sized operation inside the British government. “The scale of malevolent cyber activity is so great that it’s hard to keep track of,” admitted one former security minister.

The work now spans great swathes of Whitehall. Serious incidents are investigated by its National Cyber Security Centre, while the Home Office is responsible for prosecuting people where relevant. The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office monitors hostile states, while the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport tries to increase resilience against fresh attacks.

Security officials refused to comment on the record for this piece, but a government aide noted: “There is a massive Russian campaign to hack individuals everywhere — both personal and work emails. That has been the case long before Ukraine.”

Nevertheless, that Russian campaign only appears to be growing in the wake of the Ukraine invasion, with Moscow intent on sowing seeds of doubt about the actions and motives of its enemies. “’Hack and leak’ is a classic technique to cause embarrassment and discombobulation,” said an ex-Cabinet minister.

Burley, from the Centre for Information Resilience, said: “As the pressure ramps up in Ukraine, we can expect those on the front line of the information war to be targeted. I imagine the threat will only increase.”

He added: “It’s all about creating chaos, like the Joker in the Batman film ‘The Dark Knight,’ who wants to burn the world down. It’s about seeing what sticks.”

Mark Scott contributed reporting.

This article is part of POLITICO Pro

The one-stop-shop solution for policy professionals fusing the depth of POLITICO journalism with the power of technology

Exclusive, breaking scoops and insights

Customized policy intelligence platform

A high-level public affairs network