At the core of Doug Mastriano’s campaign are self-proclaimed prophets and QAnon conspiracy theorists

September 1, 2022 | 7:12 AM

- Katie Meyer/WHYY

Carolyn Kaster / AP Photo

State Sen. Doug Mastriano, R-Franklin, a Republican candidate for Governor of Pennsylvania, takes part in a primary night election gathering in Chambersburg, Pa., Tuesday, May 17, 2022.

At the core of Doug Mastriano’s opaque, unusual campaign for governor are a group of allies and advisors who include subscribers to outlandish conspiracy theories, self-described prophets, and people who tried to help President Donald Trump overturn the 2020 election.

A major candidate’s campaign finance report often serves as a window into the advisors they trust, and the people and organizations they’re leaning on to make their bid successful. Mastriano’s is no different — though it has little in common with most statewide campaigns in Pennsylvania.

The last reports gubernatorial candidates filed covered the period before and after the primary election. The campaign reported paying no staff salaries, and some of the payments it did make are unusual.

The self-proclaimed prophets

From February to May, nearly $43,000 from campaign coffers went to an LLC called Misfit Creates, a company whose website says it provides “content architects helping you re-imagine your narrative,” but otherwise offers little information. It’s run by Vishal Jetnarayan, according to LinkedIn. Promotional emails sent by the campaign show that he also serves as Mastriano’s campaign manager.

Related Stories

An unknown in Pennsylvania politics, Jetnarayan lives in Chambersburg, where Mastriano also lives. In book he self-published in 2011 via his own apparently-now-defunct digital media company, speaking engagements and on a religious website he runs, Jetnarayan writes that he has worked in two Chambersburg churches and describes himself, and is described by others, as a prophet. He says he speaks with God directly and gives advice on how others can do so.

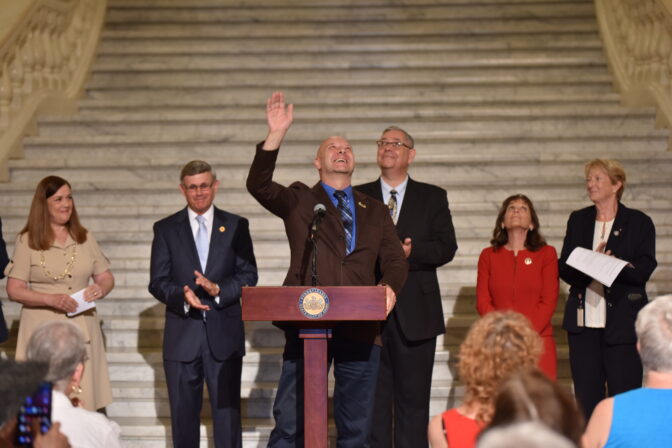

Sam Dunklau / WITF

State Sen. Doug Mastriano (R-Franklin), the 2022 Republican candidate for governor, waves to members of a crowd gathered for a rally celebrating William Penn in the state Capitol rotunda in Harrisburg on July 1, 2022.

Mastriano’s campaign seems to be paying Jetnarayan a regular salary, even though the payments are routed through a company.

Jetnarayan isn’t the only self-described prophet involved in Mastriano’s campaign. The candidate has also done events with Julie Green, another religious figure prominent in right-wing circles who says she communicates messages directly from God.

Jetnarayan, who often emcees Mastriano’s events, introduced her at a campaign rally in March, saying that she’d shared a prophecy about “God’s love for [Mastriano] … and that this was his day.”

She has previously prophesied that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi drinks children’s blood, and that a wide variety of politicians will be killed for committing treason.

The right-wing conspiracy theorist

From late 2021 to late May 2022, just after the primary, Mastriano’s campaign paid more than $82,500 for “marketing consulting” from Onslaught Media Group, a company based in Temecula, California. The office of California’s secretary of state lists Onslaught as having been suspended by the state’s Franchise Tax Board — something that happens when a company has failed to file key documents, which can include tax returns. Onslaught has been suspended in California since 2018.

Onslaught’s owner, according to LinkedIn, is Jeremy Oliver, who also describes himself as a former producer with the right-wing network One America News. Attempts to reach Oliver for comment about his LLC’s suspension or his work with Mastriano’s campaign were unsuccessful, and the campaign did not respond to a request for comment. But photos and videos from Mastriano’s campaign stops have frequently featured Oliver, and he appears to often serve as videographer for campaign events.

He also has a history of dabbling in right-wing conspiracy theories on his various social media profiles.

On his active Truth Social account — the platform Donald Trump started after Twitter banned him — Oliver has been lately sharing posts theorizing that China has or is using voting machines to hack into elections. Many of the posts use purported information from True the Vote, a right-wing group that has long sought to uncover election malfeasance but has failed to offer proof for its claims.

Among other conspiracy theories, Oliver has also posted that Russian President Vladimir Putin is in a “fight against deep state American Elites” and suggested Russia invaded Ukraine because “biolabs” in the country started the COVID-19 pandemic — a discredited idea popular in QAnon circles. He posted more explicit QAnon conspiracy content on his less active Gab account, including a variation on the abbreviation of a slogan commonly used among QAnon supporters — “nothing can stop what is coming.”

Mastriano himself has also posted QAnon content on social media.

Despite getting substantial money from the campaign and appearing frequently at events, it’s unclear if Oliver has an official title or role.

Julio Cortez / AP Photo

Pennsylvania state Sen. Doug Mastriano, R-Franklin, speaks to supporters of President Donald Trump as they demonstrate outside the Pennsylvania State Capitol, Saturday, Nov. 7, 2020, in Harrisburg, Pa., after Democrat Joe Biden defeated Trump to become 46th president of the United States.

The Trump allies

Though some of his closest campaign associates appear to be fringe figures, Mastriano also has financial relationships with several people and organizations with strong ties to Trump.

The campaign paid more than $250,000 in its most recent filing period to American Media & Advocacy Group, a conservative group Trump used in controversial ad purchases. Mastriano has also paid $40,000 to the public affairs firm C&M Transcontinental, headed by Michael Glassner, who was COO and deputy campaign manager for Donald Trump in 2016 and 2020, and was in charge of rallies for much of his tenure. A little over $3,000 also went to Brad Parscale, a former Trump campaign manager.

Mastriano has also named former Trump campaign lawyer Jenna Ellis as his senior legal advisor. Ellis was heavily involved in Trump’s effort to overturn the 2020 election. At a recent Pennsylvania Republican Party event in Erie, Ellis gave a speech on Mastriano’s behalf and hit on two campaign themes — that Mastriano believes elections cannot be trusted, and that his campaign is based on God.

“A Governor Mastriano…can appoint a secretary of state that will fairly and appropriately and, according to state law, administer elections,” Ellis said, referring to Mastriano’s plan to appoint a secretary of state who believes, like him, in the debunked theory of widespread fraud in 2020. “God gives us our rights, not our government.”

Mastriano’s spending and staff, in context

Mastriano routinely rebuffs questions from the media about his campaign, and the campaign didn’t comment for this story. That decision, as well as the decision to route routine payments through companies rather than individuals makes his campaign harder to understand than many.

The most recent financial report from Josh Shapiro, the Democratic attorney general running against Mastriano for the gubernatorial nomination, is more typical of an average campaign filing.

Shapiro spent about $7 million during May and early June. Some went to salaries for more than 15 campaign staffers, including an intern and staff for his running mate — all of whose names were listed. Many of these people have worked on campaigns before, for politicians like now-Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, Congressman Conor Lamb, and President Joe Biden.

He also spent nearly $600,000 for consulting from a variety of firms. The biggest payments went to CDT Strategies, a Silicon Valley-based firm headed by Cooper Teboe, a political operative who has said he founded it to help champion progressive candidates in primaries.

The last Republican who ran for governor, former state Sen. Scott Wagner, had a campaign finance report much more similar to Shapiro’s. In the 2018 May-to-June filing period, many of Wagner’s campaign expenditures went to payroll for 15 staffers, all identified by name in the report. He also paid several analytics and consulting firms for advertising and design.

Throughout his campaign, Mastriano’s filings have shown relatively little money. Where Shapiro ended the last filing period with more than $13 million on hand, Mastriano ended it with under $400,000.

Mastriano has noted throughout his campaign that his operation is grassroots and relies mostly on small donations, which is true. With the crowded primary over and the GOP mainstream coalescing around Mastriano, it’s likely that his next report, due in late September, will show a different financial picture.

As the gubernatorial race enters its final stretch ahead of the November election, Mastriano’s fundraising emails to supporters have ramped up and his events are getting bigger. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis recently joined him for a rally in Pittsburgh, and Mastriano is set to appear alongside Trump and GOP Senate nominee Mehmet Oz in Wilkes-Barre on Saturday.

More mainstream figures, like state GOP officials and former Delaware County Councilman Dave White, who ran against Mastriano for the Republican nomination, are now actively campaigning for him. But insiders have also noted how fringe much of the campaign remains.

One Republican operative with knowledge of the race, who spoke on condition of anonymity because of their work, said Mastriano’s campaign structure remains largely mysterious.

The operative noted Jetnarayan, the campaign manager, as an example. “I’ve never heard of the guy,” they said. “And I’ve been in Pennsylvania politics for a long time.”