Analysis | The 2020 election was neither stolen nor rigged: A primer

So allow this article to serve as one.

I’ve broken this out into three sections: Why claims of fraud emerged, why we can be confident that the election wasn’t stolen and why we can be confident that the election wasn’t “rigged.”

Why claims of fraud emerged

It’s useful to begin by explaining how this all started.

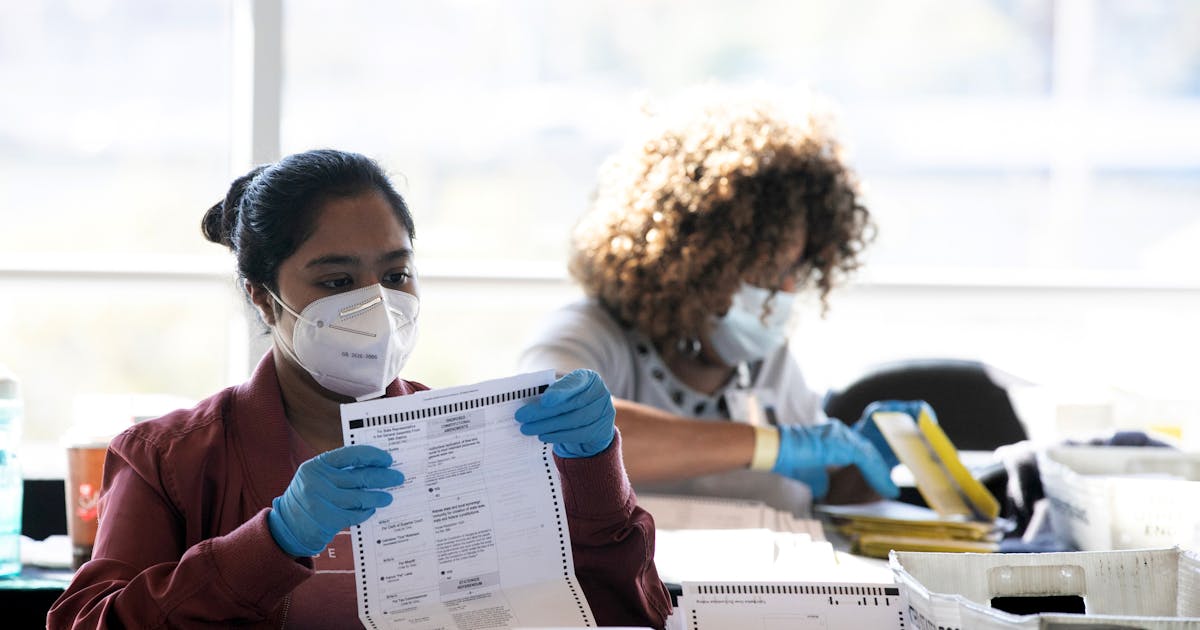

In spring 2020, the coronavirus shutdowns began just as political primaries were gearing up. States concerned about causing outbreaks of infections began bolstering mail-in voting systems, immediately triggering a backlash from Donald Trump. If the country were to increase mail-in voting, he said in late March, “you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.”

This began a months-long effort to undercut and disparage mail ballots as inherently suspect, lest more Democrats cast ballots. Numerous articles and analyses debunked the idea, but Trump — trailing in the polls — amplified it repeatedly.

As Election Day neared, Trump’s complaints crystallized into a quiet plan. Having helped widen a partisan divide in how people voted — Democrats by mail and Republicans at polling places — Trump and his allies recognized that Republican votes would be counted more quickly in many states and reported first. That would give the impression that he had a big lead that was only later eroded by votes for Joe Biden, allowing Trump to claim (as Florida Gov. Rick Scott (R) had in 2018) that the election was being stolen. So if things were close, he’d just announce his victory at the outset.

The election was relatively close. Trump and his allies tried to claim that vote counting should stop, according to the plan, but it didn’t work. As it turned out, though, his incessant claims about fraud had made it easy to convince his base that the election was stolen anyway — facilitating his multipronged effort to retain power despite his loss.

His argument about rampant fraud was so successful that, in polling conducted by Fox News this month, half of Republicans say that they have no confidence at all that votes were cast legitimately and counted accurately in 2020. Republican primary candidates found it useful to echo the idea that the election was stolen both because it often earned a Trump endorsement and because it’s what the Republican primary electorate wanted to hear.

In other words, a lot of the claims of fraud are inherently self-serving and cynical. Consider Don Bolduc, the Republican nominee for Senate in New Hampshire. During the primary he was adamant in arguing that the election was stolen. Then he won the primary and moved to the general election. In short order, he repented.

Claims of fraud, seemingly propagated in this case for political utility, had served their purpose.

Why we can be confident that the election wasn’t stolen

Let’s now assess those claims more broadly.

The best starting point is to note that there has been no — zero, nada, none — demonstrated, credible example of even a small-scale systematic effort to illegally cast votes. There have been a few dozen isolated arrests, generally of people illegally casting ballots for themselves or family members. In fact, the Associated Press contacted elections administrators in each swing state more than a year after the election, learning that, at most, there were a few hundred questionable ballots cast. In total. Across all of the states. Out of millions cast.

There are few better examples of the proper use of Occam’s razor than to therefore dismiss any idea that rampant fraud occurred. The idea that some systemic, multistate effort to rig the election occurred without detection nearly two years later — in an environment where there’s millions to be made exposing one — is simply noncredible in the face of the alternative: There was no such effort.

Of course, there is no shortage of claims about alleged fraud floating out there. These fall into one of three categories: claims that depend on vague statistical analyses, claims that depend on unseen evidence and claims that have already been debunked or explained.

Before presenting examples of each variety, it’s worth pointing to one of the most robust assessments of fraud claims. In July, a group of Republican officials released a lengthy report documenting and debunking each of the lawsuits filed by Trump and his allies in the wake of the election. It covers a lot of ground. The odds are good that if you’ve heard some claim about fraud or “rigging” (see below), it’s addressed in that document.

Now, instead of debunking each of the common allegations about fraud, I’ll simply list them and link to places where you can read more detailed analyses of why each is inaccurate.

Claims that depend on vague statistical analyses

- There was no secret “key” discovered by Douglas Frank that proves voting machines were used to guide vote totals.

- There was nothing odd or unexplained about how votes were counted in Wisconsin or other states on election night. These analyses often depend on willfully ignoring the day-of-vs.-mail-in partisan patterns mentioned above.

- The odds were not “1 in 1 quadrillion” that Biden could win as more votes were counted. (This one also ignored the partisan pattern.)

- There was no sketchy “drop and roll” process that led to Biden gaining more votes.

Claims that depend on unseen evidence

- There is no evidence that foreign actors somehow changed votes over the internet, as MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell has repeatedly claimed.

- There is no evidence that nonprofits collected illegal ballots that were then distributed to drop boxes by paid staffers, as alleged in the film “2000 Mules.” The purported evidence that was presented in that film is either false, contrived or misleading.

- Various audits of electronic voting machines have found no evidence of improprieties. In fact, swing-state counties in which Dominion Voting Systems machines were used mostly voted for Trump.

Claims that have already been debunked or explained

- Inaccurate vote totals in Antrim County, Mich., were a function of improperly configured voting machines.

- There were no rampant irregularities in Maricopa County, Ariz., just a pattern of observers not understanding voting systems and tools.

- Vote totals in states such as Pennsylvania or Wisconsin were not dependent on more people voting than were registered.

- There was no uncaught double-counting of mail-in ballots in Georgia.

There are probably examples I’m forgetting. If so, please email.

One common response to delineations like this is that of course the media/the government/the FBI are going to claim that their analysis showed no fraud. After all, you can’t have a healthy conspiracy without a gaggle of conspirators.

So we back up a step. To assume that I’m in on the con along with all of the other sources linked above is to postulate a system involving thousands or tens of thousands of people, all of whom have agreed to stay silent simply to protect Biden. Or, at least, that hundreds of people in the government have all kept quiet about agreeing to mislead the public, despite the obvious financial and moral rewards for revealing a part in such a scheme.

Occam’s razor. Who has more reason to make dishonest claims about the election, the guy trying to get people to watch his movie claiming fraud or the guy who works for a privately owned newspaper? Who is more credible on the likelihood of fraud, independent researchers or a former president eager to maintain his grip on his base?

Why we can be confident that the election wasn’t ‘rigged’

Because Donald Trump’s claims about fraud were so hard to defend, a different narrative emerged among those wishing to appeal both to Trump voters and to reality. The election may not have been stolen, exactly, but it was rigged.

The argument has two prongs. The first is that states intentionally loosened voting rules and encouraged turnout in ways that hurt Trump. The second is that the whole system — technology companies, the media, the left — arrayed against Trump to hurt his reelection chances.

It is obviously true that states made it easier to vote remotely in 2020. We’ve been over this; there was a new virus spreading and state leaders wanted to limit the number of crowded polling places. The argument, though, is that the virus was used as a pretext for making it easier to vote.

This, by itself, is revealing. There have been various arguments made about how states or counties or outside groups created opportunities for more people to vote. Sometimes, the intent is explicitly to poison perceptions of the election, as with the insistence on calling funding for expanded voting access from Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg “Zuckerbucks,” as though Facebook itself was trying to influence the outcome. But at their heart, these arguments depend on the idea that having more legal voters cast ballots in good faith is bad. That putting a drop box that hadn’t been approved by the legislature in a place where fewer people tend to vote — and where most voters are Democrats — is a grotesque effort to steal an election. Instead, of course, one might see it as an effort to unrig a system in which barriers to voting are removed and democracy bolstered.

In some cases, state officials instituted new processes for voting that were challenged by Republicans or the Trump campaign as being in conflict with state constitutions or legislative authority. This was often cited as a reason to reject the election results. But as the chief justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court put it when such a case was presented to him: “there has been too much good-faith reliance, by the electorate, on the no-excuse mail-in voting regime” to warrant tossing out the ballots. In other words, it’s silly to suggest that people told they could legally vote using mail-in ballots should see those votes thrown out and the overall results overturned because the loser of the election later raised an objection.

Then there’s the claim that the system worked against Trump. At times, this is argued with specifics, such as that the decision by social media companies to limit sharing of a story about Hunter Biden’s laptop affected the results. (This claim is often tied to a partisan, loaded survey.) But often it’s just offered generally; how could Trump win with the entire political and media culture arrayed against him? This is essentially unfalsifiable, so there’s not much more to say about it other than that this perceived bias itself often crumbles on close consideration.

There are various other after-the-fact claims about impropriety that have been debunked (there were no secret illegal ballots stashed under a table in Georgia) or dismissed (covering windows as votes were counted in Michigan was a function of a law barring videotaping the process). This was obviously part of Trump’s post-election plan, too: generate enough reports of smoke that people assumed there must be a fire. It was long the case that Trump would make contradictory claims about a situation, throwing out a large number of assertions with the understanding that he only needed people to believe one to take his side. The post-election period had thousands.

Those should not distract from the simple truth at play.

Donald Trump had reason to claim that the election was going to be stolen and later that it was.

There’s been no evidence of any large-scale effort to steal votes. There have been no rampant arrests; no one has come forward to expose such a system. This is true despite the enormous amount of scrutiny paid to the election results in nearly every state.

At the same time, there’s an obvious explanation for why Trump lost: People turned out in record numbers to vote and often did so to express approval or disapproval of Trump himself. How did Biden get 18 percent more votes in 2020 than Barack Obama did in 2008? In part because the population grew by 9 percent. But in part because Donald Trump was deeply polarizing and, as in 2018, voters wanted to send him a message.

The message was not received.