Wisconsin Republicans still fixated on 2020 election in 2022

“We know what happened in 2020,” said state Rep. Janel Brandtjen, a Republican from Menomonee Falls.

“Powerful and rich forces are aligned against me,” said Michael Gableman, a former state Supreme Court Justice.

“Was it rigged? Was it fixed? I’m going to stop it!” said Tim Michels, the 2022 Republican nominee for governor.

Republicans in Wisconsin have been amplifying Donald Trump’s debunked election conspiracy theories for nearly two years.

Rachel Rodriguez has heard them all.

“There is absolutely no glamor in elections,” said Rodriguez, an elections specialist in the Dane County Clerk’s Office. “Every time you think you have put one conspiracy theory to bed, it seems like another different one just pops up in its place.”

An elections specialist in the Dane County Clerk’s Office, Rachel Rodriguez describes the difficulty of responding to an ongoing stream of misinformation and conspiracy theories about voting in Wisconsin in an interview on Aug. 24, 2022. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

She knows every step of the process, so when Republicans in the Legislature started holding invitation-only hearings to give an official platform to election conspiracy theorists, she followed them closely.

“It was readily apparent that within minutes that the experts that they were trotting out had absolutely no expertise in actual elections,” said Rodriguez.

She started fact-checking the hearings over Twitter.

Soon, Rodriguez was being retweeted by the chair of the Wisconsin Elections Commission, and gained an audience looking for the truth.

“I think people were really looking for that other side of it — the actual expert side — because that wasn’t happening at the hearings,” she said.

Republicans hired the former state Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman to lead an investigation on the 2020 election, but what he produced was open records violations, a contempt of court order and a million-dollar bill for taxpayers.

Michael Gableman, the former Wisconsin Supreme Court justice who was hired by the Republican-controlled state Legislature to probe the 2020 election, declares he won’t answer any questions while seated in a witness box during a June 10, 2022 hearing in Dane County Court over an open records lawsuit. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Gableman was fired after endorsing the primary opponent of Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, the man who hired him.

“Mike Gableman is an embarrassment to the state,” said Vos.

Rodriguez said the cumulative effect was the truth around election conspiracies started to look like partisan politics.

“Where the problem is right now is that when you have one party — and it is one party who is driving all of this misinformation and all of the conspiracies and all of the doubt — when you take the side of actual facts and truth, which is opposite to that, it’s going to look like it’s one party over the other,” she said.

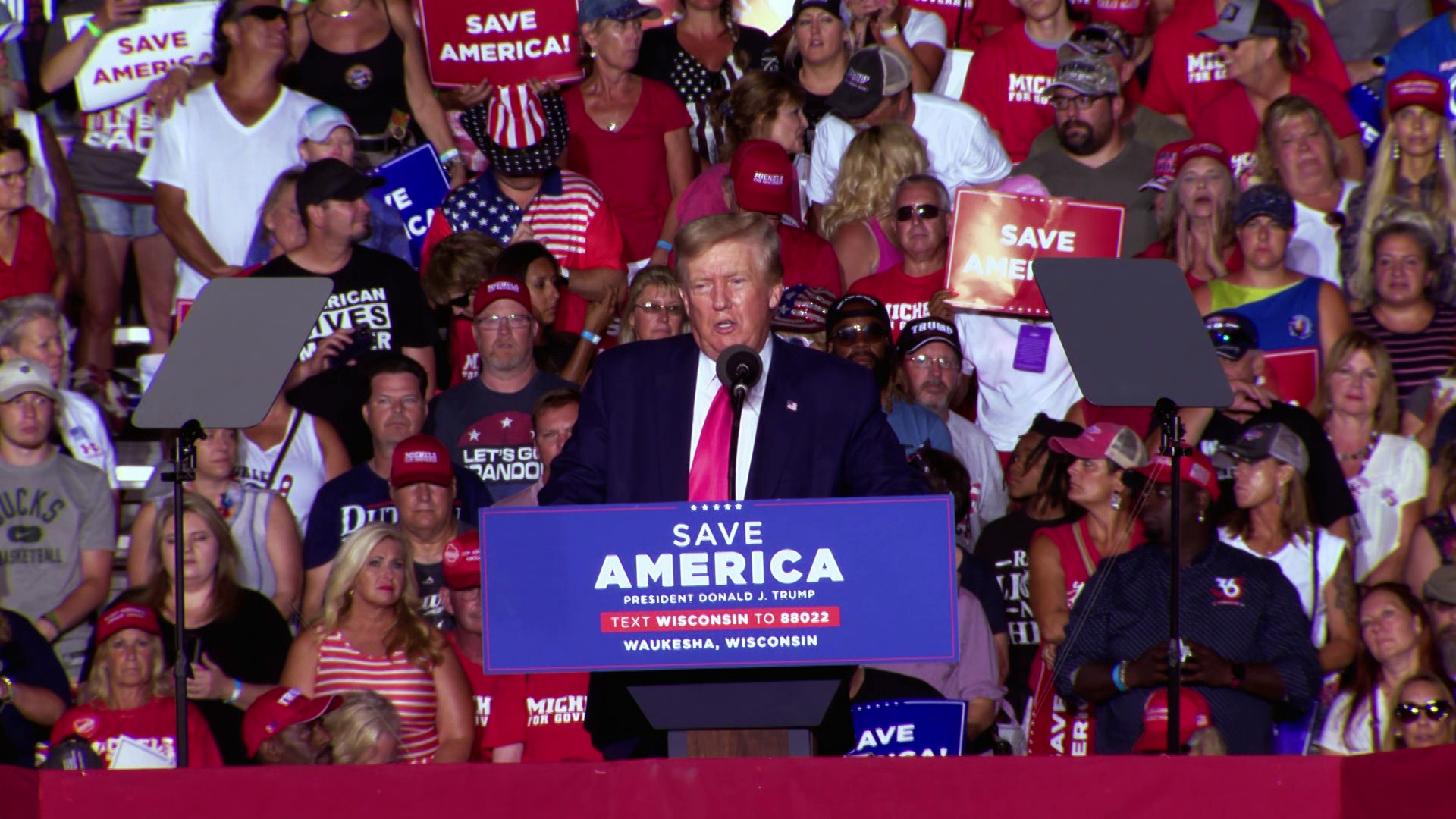

“I’m going to get rid of the Wisconsin Elections Commission,” declared Michels at an Aug. 5 rally in Waukesha where he appeared with the former president.

Michels is the Republican candidate for governor, and while he doesn’t outright say the 2020 election was stolen, he does campaign with those that do. Michels even saluted Republican state Rep. Tim Ramthun, a full-on election conspiracist who wanted to somehow “reclaim” Wisconsin’s 2020 electoral votes.

“I see my friend out here, ran a spirited primary — Tim Ramthun was very big on election integrity as well,” Michels said at a Sept. 18 rally in Green Bay with Florida’s Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis.

At one event, Michels told a supporter in order to win, he had to overcome a cheating percentage.

Tim Michels, the Republican nominee for governor in the 2022 election, speaks at the Chicken Burn, a conservative rally held in Wauwatosa on Aug. 28, 2022. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“What’s the cheating percentage? It’s probably a point or two. I think we’re going to come out ahead,” said Michels at the Chicken Burn, an annual conservative gathering in Wauwatosa held on Aug. 28.

Tim Michels did not agree to an interview for this story.

“For people to continue harboring that ‘Big Lie’ — that’s not good for democracy. It’s not good for democracy at all,” said Wisconsin’s Democratic Gov. Tony Evers.

Evers vetoed a series of Republican bills that would have changed how elections are run in Wisconsin.

“Senate Bill 292: not approved — there we go, folks,” said Evers while delivering his veto message for SB 292 on Aug. 10, 2021.

During a ceremony in the Wisconsin state Capitol’s rotunda on Aug. 10, 2021, Gov. Tony Evers vetoes SB 292, which related to broadcasting election night proceedings. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Michels has said he would sign those bills, and Democrats fear as governor, Michels could overturn Wisconsin’s presidential electoral votes in 2024.

“If they are in power and Trump comes calling asking them to change an election result, we’ve seen that they’re willing to do anything to get Trump’s approval,” said Ben Wikler, chair of the Democratic Party of Wisconsin.

“This is a very serious moment in the history of our country, and it’s hard to think of words that would be too strong to express the stakes in this fall’s election,” added Wikler.

“You know, when you look at it, election integrity has been a great topic for everybody to get some fodder both ways,” said Paul Farrow, chair of the Republican Party of Wisconsin.

“When I look back at the 2020 election, there are some challenges. We know there are issues that are there that we have to figure out how to regulate and how to make sure it doesn’t happen again,” added Farrow.

- Paul Farrow, chair of the Republican Party of Wisconsin, says changes to election regulations in the state should be made in the wake of the 2020 presidential vote.. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

- Ben Wikler, chair of the Democratic Party of Wisconsin, says members of that party are concerned Republicans could try to overturn the outcome of future elections. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“How can you lead the state if you’re afraid to tell the base of our party the truth? asked Rohn Bishop, former chair of the Republican Party of Fond du Lac County.

Bishop is concerned the GOP’s obsession with 2020 will hurt them in 2022.

“Republicans should be looking at a tidal wave election. The one way to screw it up is to keep focusing on 2020. And we keep doing that. We just can’t turn the page and focus on 2022,” he said.

Bishop was attacked by his own party members for pointing out Trump lost in Wisconsin because enough Republicans voted, but not for Trump.

“The election’s not stolen when Glenn Grothman’s getting more votes than Donald Trump in the 6th Congressional District,” said Bishop. “There was just a falloff. There were people who wanted to vote for Republican conservative principles, but not Trump.”

Rohn Bishop, the former chair of the Republican Party of Fond du Lac County and the mayor of Waupun, says fellow Republicans are too focused on the 2020 presidential vote and ostracize those who don’t subscribe to conspiracy theories about it. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Bishop said when Michels campaigns with Gableman and Trump, he risks alienating those same voters.

“Coming into 2022, Tim Michaels has to figure out how to get those 50,000 Republicans who voted Republican but not for Donald Trump,” said Bishop.

Since the 2020 election, Bishop left party politics and in April 2022 was elected mayor of Waupun, a non-partisan office.

“I just really want to focus on this job and give it all that I have,” said Bishop.

He’s still a Republican, but worries others might have left the party for good.

“Because of the hyper-partisan nature of it and the negativity, we’re busy trying to always kick people out. That’s a term that they use in our party of the RINO: Republican in Name Only. I’ve been called that by people because I didn’t think the election was stolen. Well, if you kick me out and I don’t vote for you, you’re in a lot of trouble,” said Bishop.

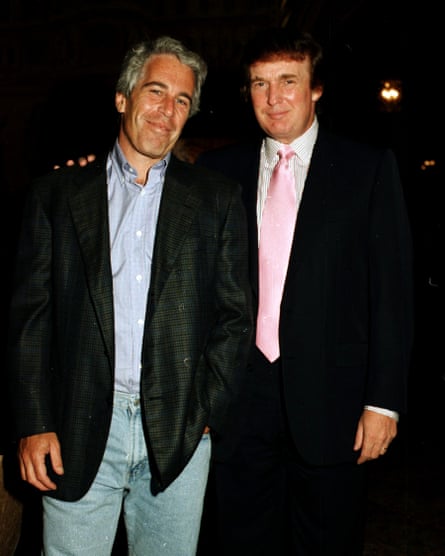

Former President Donald Trump speaks at a campaign rally in Waukesha on Aug. 5, 2022, with Republican candidate for governor Tim Michels, former Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman and state Rep. Janel Brandtjen, R-Menomonee Falls also giving speeches. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

So what impact will these conspiracy theories have on the 2022 election?

For one, there will be a lot more people in the room when voters cast their ballots.

Paul Farrow said in 2020, Republicans had about 1,300 election observers at the polls statewide.

“We are well over 5,000 this time around,” he said about the party’s 2022 plans. “We’ve got a lot more eyes that are watching the process.”

People like Christopher Bossert, a Republican from West Bend: “I had concerns about election integrity. And the best way to resolve those concerns one way or the other is to get involved. So I chose to volunteer for the Republican Party as a poll worker.”

Christopher Bossert, a member of the Washington County Board of Supervisors and resident of West Bend, is a Republican who is volunteering as a poll worker to help assuage his concerns about election practices. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Bossert said he still has concerns about voter fraud elsewhere in Wisconsin, but is no longer worried about the Dominion voting machines used in his hometown, even if his neighbors aren’t convinced.

“I have constituents who believe Dominion is a problem,” said Bossert, “and even though I’ve told them from what I can see, Dominion’s not a problem, they still believe it.