Summarising data and factors associated with COVID-19 related conspiracy theories in the first year of the pandemic: a systematic review and narrative synthesis

Database searches

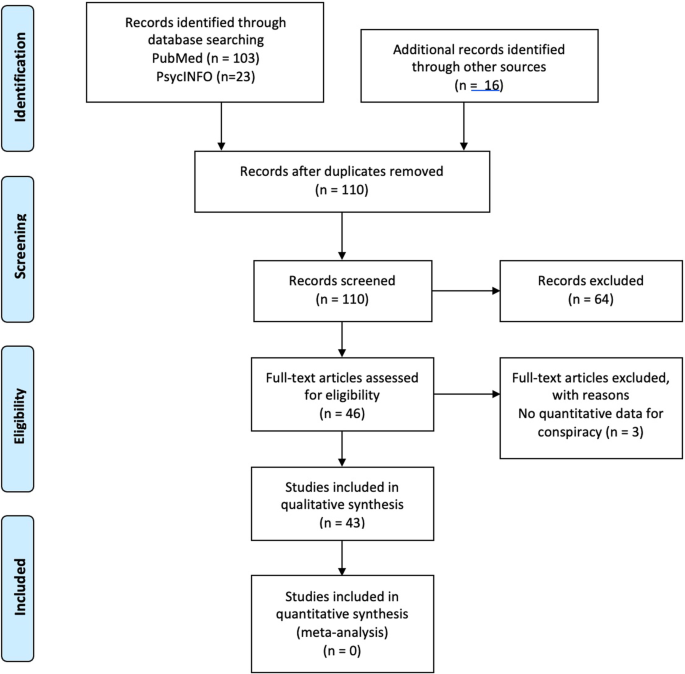

Overall, 126 records were retrieved from the database searching. Additionally, 16 records were identified through other sources. Duplicates and irrelevant studies to SARS-CoV-2 were excluded; hence, a total of 110 articles were selected. After screening the full text of the articles 43 studies were eligible for inclusion (Fig. 1).

The eligible studies were published between 2020 and 2021 [8, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]

Study description and characteristics

The 43 eligible studies included a total of 14,172 posts and 61,809 participants with a median number of participants of 845 (IQR = 624 -2.057), median number of mean age of 37 years (IQR = 31- 40.2), and a median number of 58.8% of women. Eleven studies (25.6%) were conducted in the USA and seven (16.3%) in the UK. The remaining studies were conducted in various other countries as shown Tables 1 and 2. Most of the studies (88.1%) employed a cross-sectional study design using a convenience sampling method, while six studies were qualitative including analysis of tweets or posts in the social media and other sources (Table 2). No randomized studies were found. Most of the studies (58.1%) were of moderate quality. The characteristics of the included studies are summarised in Tables 1 and 2.

Conspiracy theories and beliefs—content and prevalence

All of the studies examined various conspiracy theories, such as the 5G network theory, the theory of laboratory-created SARS-CoV-2, the theory of intentional spread of the virus, the Bill Gates/ microchip/ vaccine narrative, with the exception of one study which examined non-specific, SARS-CoV-2 related conspiracy ideation[34]. The overall percentage of participants from 28 studies (including qualitative studies) who reported agreeing with one or more conspiracy beliefs ranged from 0.4 to 82.7% [8, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23, 28,29,30, 32, 33, 35,36,37,38, 40, 41, 43,44,45,46, 48, 52, 53, 57, 58]. Because most studies provided average percentages of the different narratives calculated altogether, as well as the overlap of various conspiracy theories, it could not be determined whether certain conspiracy theories were more widespread than others. However, when we grouped them into the above-mentioned narratives/categories, only 5.0% believed in the natural origin and spread of the virus, while 39.0% believed in the intentional spread of the virus for political reasons (Fig. 2).

In regards with specific conspiracy theories, 21–34.8% of participants believed that 5G and COVID-19 were somehow linked and that 5G networks enhanced the spread of the virus [18, 44, 45]. Concerning the microchip narrative, 27.2% and 27.7% of participants in USA and Arab countries respectively believed that coronavirus vaccine will contain microchips that control people, or that COVID-19 vaccines are intended to inject microchips into recipients (and will also cause autism or infertility) [26, 43]. Theories of the virus being laboratory created were fairly widespread: only 20.6% to 29% of participants in Greece, 54% in Turkey and 63% in UK believed that SARS-CoV-2 came about naturally. At the same time, 13.9% of participants in Ecuador believed that coronavirus was created accidentally in a lab, while 24.2–58.5% of participants in Arab countries, Poland and Ecuador believed that COVID-19 was developed intentionally in a lab [43, 57, 58]. In addition, and as previously highlighted, theories of intentional spread of the virus were also quite prevalent, with 13.3% of Americans endorsing the belief that China spread the virus purposefully [33], 24% of Greeks that it was developed as a bio-weapon [28] and 57% of Jordanians that there was a biologic warfare role in the origin and spread of the virus [44]. Detailed specific conspiracy theories and their prevalence are described in Tables 1 and 2.

Characteristics of believers in COVID-19 related conspiracy theories

There was a large heterogeneity in the factors associated with the COVID-19-related conspiracy theories, so we divided them into three categories (Table 3). Details per study are presented in Additional file 1: Table 3.

Sociodemographic characteristics potentially associated with conspiracy theories and beliefs

Several sociodemographic characteristics were associated with conspiracy theories and beliefs (see Table 3). Overall, five studies showed that conspiracy beliefs were associated with younger age [19, 22, 29, 33, 36] with effect sizes of 95% CI (− 3.22 to − 0.50), p = 0.007), r = − 0.42, p < 0.001 and AOR = 0.97, p < 0.05 for the Allington, Freeman and Latkin studies respectively. One study [30] showed that age did not have a significant impact on conspiracy thinking. The majority of the studies (5 in total) showed that female gender was associated with higher belief in conspiracy theories [35, 38, 40, 43, 44], whereas only one study showed that men had stronger agreement with misinformation [36] and two studies revealed no relationship between gender and conspiracy beliefs [29, 30]. Regarding ethnicity, being white (4 studies) was associated with lower levels of conspiracy beliefs and/or increased belief in the natural origin of the virus [8, 19, 22, 38], while an Australian study found that stronger agreement with misinformation was associated with a language other than English spoken at home [36]. Furthermore, conspiracy beliefs appear to be more prevalent in those who are married (and divorced/widowed/ separated) compared to single, and to those who have children compared to those who do not [38, 44]. For example, in Sallam’s study, the belief that COVID-19 is part of a global conspiracy and the overall belief in the role of 5G networks in the spread of COVID-19 were more common among married participants compared to single participants (50.5% vs. 45.8%, p = 0.011; χ2) and (23.1% vs. 19.4% among singles, p = 0.017; χ2) respectively [44]. Another study showed that marital status had a significant association with conspiracy beliefs, but with less straightforward results [58]: more specifically, married persons were about 1.5 times more likely to believe the theory that the pandemic is used for political purposes (OR, 95% CI: 1.49, 1.02–2.17), while those who were widowed, divorced or separated were about 1.8 times more likely to believe that the pandemic is being used as a pretext for the introduction of a system of total surveillance (OR, 95% CI: 1.77, 1.08–2.91) [58].

Five studies showed that income is inversely related to conspiracy theories, i.e. higher income is related to reduced conspiracy thinking, compared to lower/middle income [8, 30, 38, 40, 44]. For example, in the Kim study [30] beliefs in conspiracy theories were high among households with incomes below 300 million won and were relatively lower in the two groups with incomes of 300 million won or more. On the other hand, one study showed no association between level of income and conspiracy thinking [58]. Furthermore, several studies (eight in total) showed an association between lower educational level and increased belief in conspiracy theories [8, 22, 24, 36, 38, 43, 44, 58]. For example, those who had a master’s degree or higher were less likely to accept the theory about the emergence of a genetically manipulated new coronavirus (OR, 95% CI: 0.5, 0.32–0.78) [58], while beliefs in COVID-19-related conspiracy theories were higher in those with a high school education compared to college degree graduates [24]. Similarly, in Salali’s study, those with postgraduate degrees had increased odds of believing in the natural origin of the virus compared to those without a graduate degree (Turkey: OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.31–2.03, p < 0.001, UK: OR 2.40, 95% CI 1.70–3.39, p < 0.001) [38]. Only one study found that education was associated with greater endorsement of conspiracy beliefs[19] and another one showed no statistical significant relationship between lower education and beliefs in conspiracy theories [30]. Interestingly, a Greek study highlighted that students of theoretical studies in particular, showed higher belief in conspiracy theories [35].

Finally, concerning physical health status, one study showed that those with better health were more likely to endorse conspiracy theories (AOR = 0.56, p < 0.01)[33], while another study showed that there was no correlation between health status before COVID-19 and conspiracy theories, however, there was a positive relationship with health status after COVID-19 i.e., after worsening of health status (Pearson’s r = 0.292, p < 0.001)[30]. Details per study are presented in Additional file 1: Table 3

Psychological aspects potentially associated with conspiracy theories and beliefs

As evidenced in Table 3, an array of psychological characteristics and aspects were found to predict conspiracy theories and beliefs. Details per study are presented in Additional file 1: Table 3.

For example, people who are less tolerant of uncertain situations and with higher levels of impulsivity were more likely to believe in COVID-19 conspiracy theories (r = − 0.178, p < 0.001) [39]. In regards with perceived risk/perceived threat from COVID-19, three studies showed that it was inversely related with conspiracy theories [8, 36, 39] On the contrary, one study showed that beliefs in conspiracy theories were positively related to perceived risk [30]. Perceived lack of self-control had a negative effect in conspiracy theories, i.e., groups with lower perceived control had stronger beliefs in conspiracy theories [30].

One study highlighted the importance of what could be called an overall conspiracy “mindset”: higher levels of coronavirus conspiracy thinking were associated with an overall conspiracy mentality, which included conspiracy beliefs about vaccines in general, climate change conspiracy theories, and an overall distrust in institutions and professions [22]. Other psychological factors that may be associated with stronger beliefs in conspiracy theories (especially the beliefs that vaccine was ready before the outbreak, biological warfare, and the role of 5G networks in the origin and spread of the virus) included higher anxiety, negative emotions, current presence of distress (OR = 2.44, 95% CI 1.20, 4.98, p = 0.014) [57] or depression, pessimism, emotional disorders symptoms and pain (ρ = 0.12—0.21, all p’s ≤ 0.001)[27, 32, 44]. However, there was inconsistency concerning the role of anxiety and stress surrounding COVID- 19. More specifically, two studies could not confirm the association between coronavirus related anxiety, self-reported stress and conspiracy beliefs [24, 32], while one study found that higher level of anxiety about COVID-19 was associated with the belief that the disease is part of a conspiracy [40] and a second study also demonstrated that people with higher anxiety had stronger beliefs in conspiracy theories [30]. In regards with depression and self-destructive behaviour, one study showed no relationship between history of depression, self-harm or suicidal attempts and any conspiracy beliefs concerning COVID-19, however, the current presence of distress or depression was significantly correlated to the belief that the vaccine was ready before the outbreak (χ2 = 23,088, df = 8, p = 0.003) and that there is a relationship to 5G (χ2 = 26,426, df = 8, p < 0.001) [20]. Interestingly, one study highlighted that health care workers who believed the virus was developed intentionally in a lab had lower life and job satisfaction than those who were unsure how the virus originated [57].

Further, another psychological factor, namely anger was related to conspiracy theories and beliefs. More specifically, beliefs in 5G/ COVID-19 conspiracy theories were significantly and positively correlated with state anger, which in turn, was associated with a greater justification of (total effect = 0.44, 95% CI[0.37, 0.52]) and willingness for (total effect = 0.19, 95% CI [0.14, 0.24]) real-life violent response to a hypothetical link between 5G networks and COVID-19 [25]. Finally, external blame, low trust in people, persecution and boredom were significantly correlated with conspiracy beliefs, as suggested by two studies [30, 32]. Details per study are presented in Additional file 1: Table 3.

Religion, political orientation, trust in science, sources of information and other factors potentially associated with conspiracy theories and beliefs

Four studies examined the role of religiosity and found consistent evidence that conspiracy beliefs were associated with higher religiosity (AOR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.02–1.22) [18], (r = 0.231, p < 0.001) [23, 30, 39]. In addition, several studies indicated a relationship between rightist/conservative political beliefs and higher rates of conspiracy theories (r = 0.165, p < 0.001) [39], (AOR = 1.32, p < 0.01) [18, 19, 22, 30, 33, 36, 38, 46, 51]. One study showed that both ends of political spectrum (right and left) are related to increased conspiracy beliefs [23], and the same holds for those who believe that it is not worth voting in a general election [22]. Moreover, conspiracy theories appear to be linked to lower trust in government and a perception that governments and politicians are either hiding information(r = 0.28, p < 0.01) [24], or being dishonest about their ‘true’ intentions, in order to achieve political aims or introduce a system of total surveillance [30, 58]

With respect to scientific reasoning, analytic thinking and trust in science the results showed that these factors were inversely related to conspiracy theories (Pearson’s r = − 0.134, p < 0.001)[18, 19, 30, 36, 40, 42, 56]. People with greater trust in science were less likely to consider conspiracy narrative statements to be highly plausible (AOR = 0.20, 95%CI = 0.12–0.33) [18]. One study, however, found no relationship between trust in doctors and conspiracy theories [30]. Results from one study showed that belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories was positively correlated with faith in intuition (r = 0.206, p < 0.001) [39]. Furthermore, reduced knowledge about COVID-19 was positively correlated with conspiracy beliefs [40]. Also, people who reported higher scepticism were less likely to believe people close to them would die from COVID-19 (AOR = 4.2, p < 0.01), and those who were more sceptical about COVID-19 were also more likely to believe the conspiracy theory that China purposefully spread the virus (AOR = 6.38 p < 0.01)[33].

Another important factor that emerged to be associated with conspiracy thinking was the source and quality of information about COVID-19. One study showed that better quality of information around COVID-19 was related to fewer conspiracy theories (Pearson’s r = 0.414, p < 0.001) [30]. Adding to this, several studies highlighted that use of social media as source of information on COVID-19 was related to higher levels of conspiracy thinking (95% CI (0.62–0.67, p < 0.001) [19, 29], (Pearson’s r = 0.134, p < 0.001) [8, 22, 30, 36, 43, 58]. At least three studies found that YouTube is one of the sources of information mostly associated with conspiracy beliefs [22, 29, 45]. Furthermore, one study indicated that mainstream TV news play a larger role than other news media in not legitimising COVID-related conspiracy theories [8] and similarly another study showed that use of legacy media (i.e. print media, radio broadcasting, and television) as source of information for COVID-19 was negatively associated with conspiracy theories (95% CI (0.42–0.48), p < 0.001) [29]. However, reliance on conservative media was positively related to endorsing conspiracies [8]. Moreover, information related to coronavirus from family and friends was associated with higher levels of conspiracy theories (95% CI (0.57–0.63), p < 0.001) [22, 29], while participants who endorsed conspiracies reported less trust in information coming from governmental institutions and people like Anthony Fauci [19].

Finally, one study examined the role of social dominance orientation/traditionalism and found that people with high social dominance orientation and low traditionalism were less inclined to share COVID-19 conspiracies and miscellaneous COVID-19 misinformation claims [50]. Interestingly, another study showed that people who hold COVID-19-related conspiracy beliefs were more likely to endorse positive statements about the outcomes of the pandemic [22]. These findings are summarised in Table 3 and details provided in Additional file 1: Table 3

Consequences and repercussions of conspiracy theories

Several studies within this systematic review reported a negative correlation between conspiracy thinking and complying with public health recommendations and public health and government measures [8, 22, 24, 29, 34, 42, 54, 55]. For example, people who reported increased belief in conspiracy theories at any wave tended to report less social distancing at the following wave [55], whereas those who endorsed the statement ‘Coronavirus is a bioweapon developed by China to destroy the West’ were much more likely to also not adhere (defined as less than most of the time) to ‘stay at home’ recommendations (OR 14.34, 95% CI 11.26–18.25) [22]. Greater scepticism was also strongly associated with reduced engagement in COVID-19 prevention behaviours, including confinement at home to prevent coronavirus (AOR = 0.33, p < 0.01) and frequently wear a mask outside (AOR = 0.44, p < 0.01) [33]. However, three studies showed that conspiracy beliefs were unrelated to adherence to safety guidelines [19, 31, 39]. Regarding attitudes towards the -then upcoming- vaccines there were similar findings. Results from eight studies showed that beliefs in conspiracy theories were associated with negative attitudes towards future vaccination [49] and negatively affected the intention to receive a vaccine once one became available [8, 19, 22, 37, 40, 42, 43]. Similarly one study found that believing in the natural origin of the virus significantly increased the odds of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance [38]. Details per study are presented in Additional file 1: Table 3.