QAnon ideas proliferate in 2022 midterms, raising continued concerns of violence

David DePape had the tools he believed he needed to send a message to members of Congress: a hammer, zip ties and a plan to break House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s kneecaps “if she lied.”

He later told authorities that if he had executed his plan, “she would then have to be wheeled into Congress, which would show other members of Congress there were consequences to actions,” according to an FBI report. San Francisco prosecutors have since said other leaders were in his sights.

DePape, 42, faces federal and state charges after authorities say he broke into Pelosi’s home and violently beat Pelosi’s husband with a hammer. Nancy Pelosi, long a top target of threats and misinformation, was in Washington, D.C., during the Oct. 28 attack. Paul Pelosi is recovering from a fractured skull and other injuries; he was released from a hospital Nov. 3.

Before the invasion, DePape espoused some ideas associated with QAnon, a conspiracy theory invoking pedophilia and a Democratic cabal that the FBI has long warned could lead its adherents to commit violence.

QAnon rhetoric provided some of the fuel for the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol. Rioters then similarly called out for Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., as they ransacked congressional offices, giving air to the false idea that the 2020 presidential election was fraudulent.

Days from the Nov. 8 elections, the Pelosi attack reinforces how threads of the false narrative have woven themselves into the midterm mindset, heightening the potential for violence. Numerous political campaigns sprung from Q-aligned concepts like election denialism, with former President Donald Trump amplifying these fantastical ideas on his own Truth Social platform.

Despite some platforms’ high-profile efforts to eliminate QAnon content, references to deep state conspiracies, stolen elections and more QAnon themes continue to appear on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, TikTok and Twitter.

DePape attorney Adam Lipson told reporters his team will explore how these ideas might have affected DePape: “There’s been a lot of speculation regarding Mr. DePape’s vulnerability to misinformation, and that’s certainly something we are going to look into.”

The link was clear to Mia Bloom, a Georgia State University communication and Middle East studies professor and international security fellow at New America.

“This attack on Mr. Pelosi was a movement from consumption of radical content to actually engaging in violence,” Bloom said.

Violence and threats linked to QAnon beliefs

DePape told San Francisco police officers he viewed Pelosi “as the ‘leader of the pack’ of lies told by the Democratic Party. On Facebook, he had shared videos that falsely claimed the 2020 was stolen. He posted links to websites that claimed COVID-19 vaccines are deadly. And he shared transphobic images, CNN reported. On blogs linked to DePape, PolitiFact found posts titled “Take the Red Pill,” “Q,” “Gamer Gate,” “No evidence of election fraud,” and “Fall of the Cabal.”

A police officer rolls out more yellow tape on the closed street below the home of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and her husband Paul Pelosi in San Francisco, Oct. 28, 2022. (AP)

His example should not be seen in isolation.

On the same day DePape attacked Pelosi, a man in California was found guilty of murder in a QAnon-inspired plot to kill sex offenders.

Other cases have connected QAnon beliefs and mental health issues with familial violence.

-

In Michigan, police said Igor Lanis shot his wife, his eldest adult daughter and the family dog Sept. 11. Police killed Lanis during a subsequent armed standoff; only his daughter survived the attack. After the attack, his younger daughter told news outlets her father was a QAnon believer.

-

A California man confessed to the 2021 killing of his two young children with a spear gun. He told an investigator he had been “enlightened by QAnon and Illuminati conspiracy theories,” and feared his children had serpent DNA, The Associated Press reported.

-

Colorado mother Cynthia Abcug was involved in planning a raid to kidnap her son from foster care in 2019. Her teenage daughter said the plot emerged after Abcug began associating with QAnon adherents.

Threats against election officials and members of Congress and the judiciary have increased sharply since Trump’s 2016 election.

In September, a man who was arrested after an incident at a Dairy Queen restaurant in Pennsylvania told investigators he had a loaded gun in his pocket to protect himself from drug traffickers and that he “intended to kill ‘Democrats and liberals’ and wanted to ‘restore Trump to president king of the United States,’” according to local news reports. His online presence included posts and videos featuring QAnon phrases such as “the deep state.”

DePape repeatedly told officials investigating his attack that he’d been “fighting against tyranny without the option of surrender,” according to a federal criminal complaint.

During the attack, Paul Pelosi reportedly asked DePape why he wanted to see Nancy. According to state court filings, DePape said: “Well, she’s number two in line for the presidency, right?” When Paul Pelosi agreed, DePape “responded that they are all corrupt and ‘we’ve got to take them all out,’” said the court document.

That document also said DePape repeatedly said he had more targets than Pelosi, including “a local professor, several prominent state and federal politicians” and their relatives.

Despite repeated warnings about the growing threat of political violence, popular Republican figures including Trump, members of Congress and candidates continue to allude to QAnon conspiracy theory narratives — or, in some cases, invoke the theory outright.

Trump, other conservative figures continue to amplify QAnon narratives

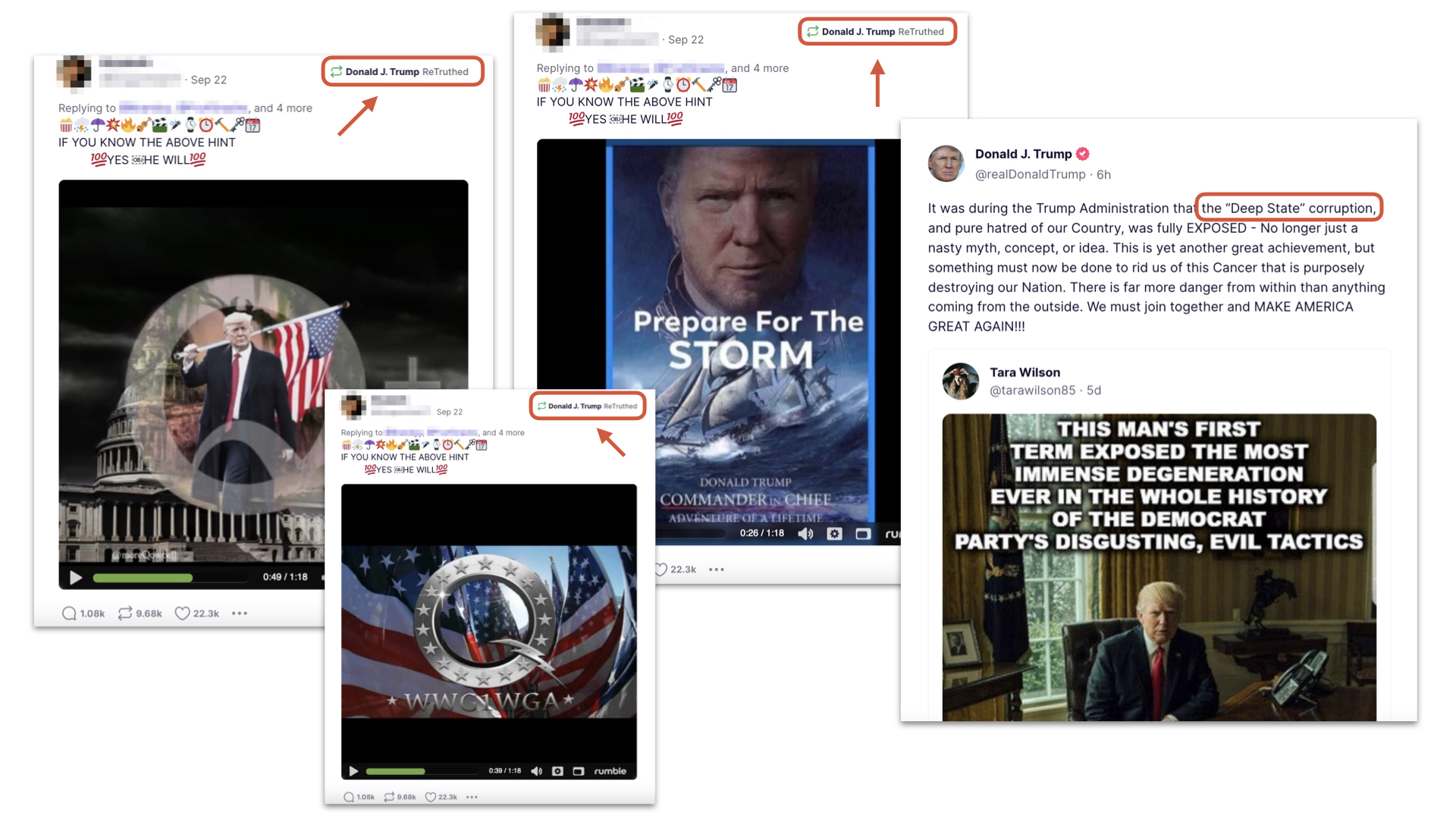

Trump has embraced QAnon imagery on Truth Social, his social media site. On Sept. 22, he reshared a video of QAnon phrases including the “storm” and the “WWG1WGA” sequence, as well as a photoshopped image of himself inside a “Q+” symbol. Many QAnon proponents call Trump “Q+.”

Of nearly 75 accounts Trump reposted on his Truth Social profile from mid-August to mid-September, more than a third promoted QAnon by sharing the movement’s slogans, videos or imagery, according to the AP.

Examples of imagery or phrases that Trump has reshared or written himself on Truth Social. (Screenshots from Truth Social)

In QAnon communities there are “millions of people who are committed to a certain idea that is pro-Republican and pro-Trump,” said Heidi Beirich, co-founder of the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism. “Why not tap into that — either by sort of dog whistling to QAnon, or being more overt like Trump is being?”

Trump’s recent public embrace of QAnon may signal that if he is not treated as he believes he should be, he can call on an army of dedicated followers, said Bloom, who co-authored the book, “Pastels and Pedophiles: Inside the Mind of QAnon.”

Despite moderation efforts, QAnon-linked conspiracy theories remain online

In October 2020, Meta, YouTube and TikTok all announced plans to crack down on QAnon-associated content.

Meta said it would remove QAnon Facebook pages, groups and Instagram accounts, even if they contained no violent content. Thousands of QAnon-linked profiles and pages have been taken down, it said.

YouTube announced it would prohibit videos that target people with “conspiracy theories that have been used to justify real-world violence,” such as QAnon. It deleted more than 10,000 QAnon videos and hundreds of channels, it said.

TikTok said it banned all content or promotion of videos that advance QAnon conspiracy theory ideas.

Months later, after the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, Twitter removed more than 70,000 accounts that promoted “harmful QAnon-associated content.”

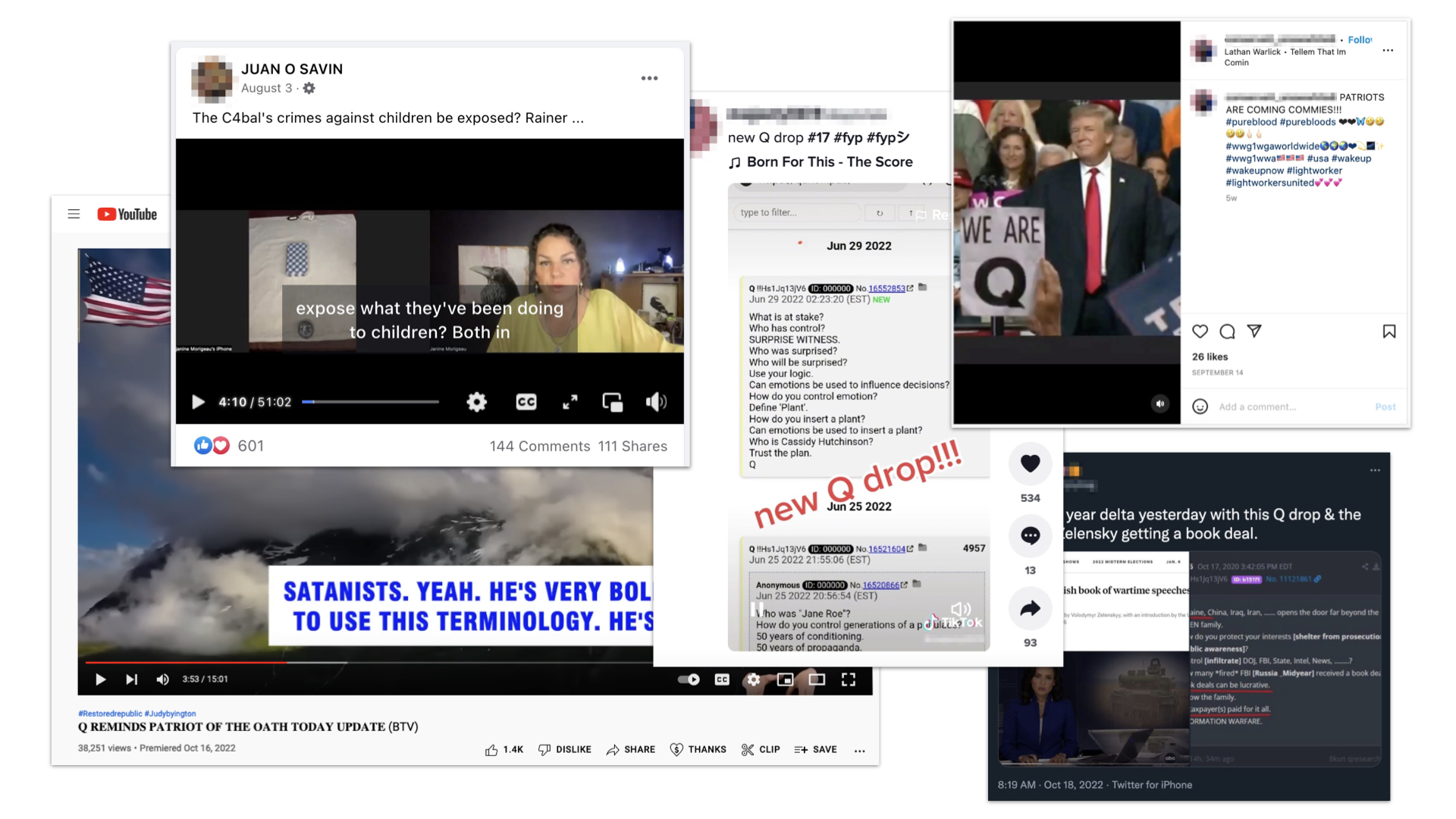

But QAnon-linked claims and narratives persist. In some cases, it’s because the creators have evaded moderation by using coded language or because QAnon adherents simply moved to platforms that were more hospitable to false information.

Even overt QAnon language and rhetoric persists on widely used social media platforms. The above examples were pulled from YouTube, Facebook, Tiktok Instagram and Twitter in October 2022. (Screenshots from respective platforms)

Some networks turned to alternative tech platforms. This includes sites such as Gab, a cross between Facebook and Twitter that brands itself as a “free speech social network”; Truth Social; Telegram, an encrypted messaging app that grew by millions of users after Jan. 6, 2021; and Rumble, a video platform that markets itself as being “immune from cancel culture.”

Pew Research Center on Oct. 6 published findings showing that seven of such platforms — BitChute, Gab, Gettr, Parler, Rumble, Telegram and Truth Social — feature prominent accounts that commonly share QAnon related content.

There are so many QAnon narratives and ways to make claims without using “traditional QAnon language,” that it presents a challenge for mainstream social media platforms that have tried to crack down on QAnon content, said Beirich of the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism. “AI systems have to constantly be retrained with new phrases, new ideas.”

Some conservative politicians have embraced this approach, alluding to QAnon narratives in ways that are less blatant. That’s political strategy, Bloom said.

For example: Kristina Karamo, the Trump-backed Republican candidate for secretary of state in Michigan, advanced one of the most outlandish QAnon ideas, that elites are tied to child sacrifice, in November 2020. While running for statewide office, she has tried to distance herself from QAnon beliefs despite speaking at events organized by QAnon proponents.

Leading up to the election, Karamo has repeatedly made unproven claims about election fraud in apparent nods to QAnon-linked narratives: “Systemic fraud in our system has gone on for years,” she wrote on Twitter Oct. 19. “Everyone in Michigan knows it. Everyone in Michigan feels it.”

‘Stop the steal’ QAnon rhetoric expected to intensify surrounding midterms

A QAnon believer speaks to a crowd of President Donald Trump supporters outside of the Maricopa County Recorder’s Office where votes in the general election are being counted, in Phoenix, Nov. 5, 2020. (AP)

When QAnon first emerged in 2017, its anti-pedophilia focus called adherents to “save the children” and stop the deep state cabal. The narrative hinged on the false idea that Trump was working behind the scenes to bring those in the cabal to justice.

Election denialism was folded in after 2020 and remains a key element, said Beirich. A coalition of Republican election deniers — some of whom could still win statewide positions following the Nov. 8 election — endeavored to take control of elections offices in swing states like Nevada, Arizona, Michigan and Pennsylvania. An influential QAnon conspiracy proponent formed that coalition.

When a Category 4 hurricane hit Florida, one former Republican candidate with QAnon ties suggested it was a plot by “the deep state” to take out conservative-leaning communities just weeks before the election.

In QAnon ideology, all things that negatively affect the theory’s proponents are attributed to the “deep state cabal,” said Bloom. So, if QAnon supporters’ favored candidates lose midterm elections, “stop the steal” language could return even more forcefully.

“They’re refocusing on the election and Trump,” Beirich said. “It seems to me, they’re sort of revving up for 2024, right? It’s not just the midterms that are coming.”

PolitiFact reporter Gabrielle Settles and researcher Caryn Baird contributed research to this report.

RELATED: Election officials, lawmakers in Congress have faced increase in threats

RELATED: Misinformation fuels false narratives about attack on Paul Pelosi

RELATED: QAnon, Pizzagate conspiracy theories co-opt #SaveTheChildren

RELATED: What is a MAGA Republican?