Counting Through Conspiracy Theories in Arizona’s Midterms

The board of supervisors, which Gates was elected to six years ago, generally handles bureaucratic miscellany: zoning, animal control, paving dirt roads. The board used to be “sleepy—important, but kind of sleepy,” Gates said. The gig was ostensibly part-time. (He also works as a lawyer for a golf company.) In elementary school, Gates had made a passionate speech extolling Gerald Ford to his classmates, and as a teen-ager, he’d founded his school’s Republican Club. His love for the Party was a central pillar of his identity, and he understood himself to be a member of the state’s G.O.P. establishment. Then the Party changed beneath his feet. Trump zeroed in on Arizona early in his first Presidential campaign, and his rowdy populism played well here. Gates voted for Trump in 2016. He found the former President rude, bordering on offensive, but liked the judges he appointed and the giant tax cut he passed.

In 2020, Arizona went for Joe Biden, and votes in Maricopa were what pushed it over the edge. Amid allegations of fraud, the county commissioned one audit after another; all of them upheld the outcome. Gates was alarmed when some of his Republican colleagues, people he had considered friends, began to echo false claims about the election being stolen. It seemed to him that they were feeling heat for losing, and were trying to find somewhere else to place the blame. “But we, as a board—we don’t have any choice,” Gates said. “We ran the election, we certified the election. We couldn’t try to fob this off, or tell people what they wanted to hear.” On January 6, 2021, as rioters stormed the Capitol in D.C., a group set up a guillotine outside Arizona’s capitol building, and issued a statement demanding additional election audits and investigations. “We pray for Peace, but we do not fear war,” it concluded.

In February, all of Arizona’s sixteen Republican state senators called for the board to be held in contempt and its members arrested. Gates filmed a sort of hostage video in his office, saying, essentially, “If you’re watching this video, I’m in jail.” He wanted the American people to see how out of control things were getting. He thought, If they want a perp walk, I’m going to give them a perp walk. At the last minute, one Republican senator bucked his colleagues, and the arrests were averted. The senate then hired an inexperienced, partisan firm called Cyber Ninjas to conduct yet another audit of the Maricopa ballots, a process that was roundly derided. It took place in Arizona’s Veterans Memorial Coliseum, which Gates could see from his office window. He never visited. “There were multiple signs up over there about, you know, doing harm to the board of supervisors,” he said.

Gates and Richer (who is also a lifelong Republican) had tried to remain above the political fray. As the audit unfolded, they decided they needed to make a stronger statement. They held a press conference, where Gates walked in front of a phalanx of cameras and said, “I’m Bill Gates. I’m the chair of the Maricopa County board of supervisors, and Joe Biden won Maricopa County.” It didn’t have the impact he’d hoped for. “We stood up, and we hoped that there would be a lot of others who would stand up,” he said. “And other than a few, it really hasn’t happened.” The Cyber Ninjas audit confirmed Biden’s victory. Less than a year later, a wave of election-denying candidates won the state’s Republican primaries anyway.

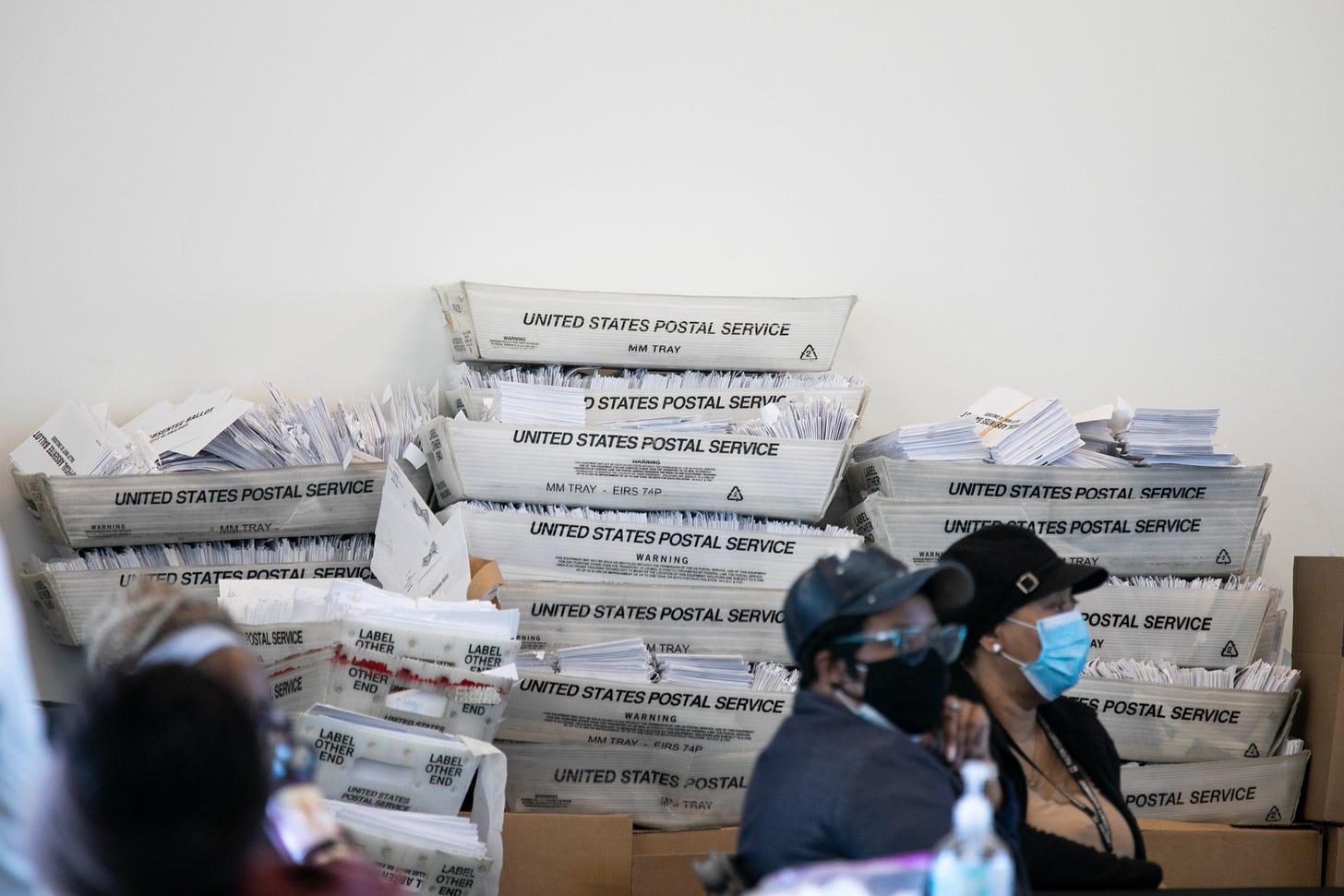

Trump’s allies continued to scrutinize the 2020 election, and Gates understood that the level of attention on this year’s contest, and on him personally, would be intense. He and Richer pledged to run the most transparent election possible. There was already a twenty-four-hour live feed, with multiple angles, of the ballot vault and the rooms where voter signatures would be verified. They added more cameras to the feed. The tabulation itself would take place in a secure room, also covered by multiple live feeds. Even the wiring of the tabulator machines was exposed, so observers could clearly see what was connected to what. They posted YouTube videos that explained, in Spanish and English, the security features of the machines.

Arizona has a decades-long history of mail-in voting, and most of the state’s voters cast their ballots that way. Recently, some Republican candidates have begun to call mail-in voting untrustworthy. (Mark Finchem, the Republican candidate for secretary of state, has pushed to restrict the practice and to end early voting, although he has reportedly voted early twenty-eight times since 2004.) Leading up to Election Day, Richer was concerned that more in-person voting would lead to longer lines, even though the county had increased the number of polling places. The evening before the election, he led me through the hallways of Maricopa County’s tabulation and election center. The building, in downtown Phoenix, was encircled by security fencing, in anticipation of protesters. Richer’s hair was frazzled and he had dark circles under his eyes, but he spoke quickly and precisely. He stopped in front of a wall covered with large maps. “These show where people voted in past elections,” he said. “We try to make our decisions based on past data. Unfortunately, voting behaviors are changing these days.”