Fact Check: COVID-19 Vaccines, PCR Tests Do NOT Make People ‘Magnetic’

Do COVID-19 vaccines or PCR tests make people “magnetic”? No, that’s not true. There is no evidence that either of them can increase what is perceived as “magnetism.” But theatrical glue, oily skin or body cream can do the trick of making objects stick to skin without fundamentally altering the properties of the human body, which is not known for magnetic qualities.

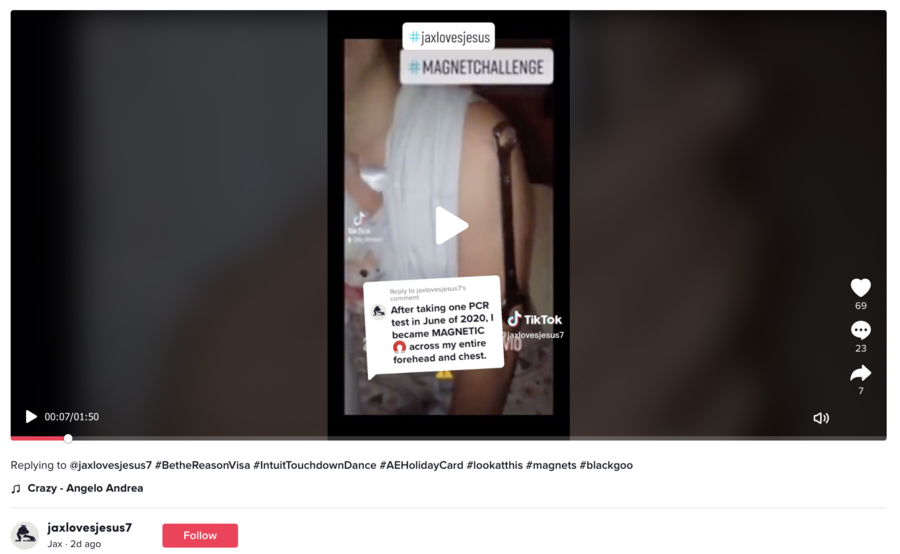

The claim appeared in a video (archived here) posted on TikTok on November 21, 2022. The original audio was recorded in French, but the video opened with an English-language text graphic:

After taking one PCR test in June 2020, I became MAGNETIC across my entire forehead and chest.

When the caption disappeared, the video showed the following text:

2E DOSE VACCIN ANTI COVID

The English translation is “2nd DOSE ANTI COVID VACCINE.”

Here is what the video looked like at the time of the writing of this fact check:

(Source: TikTok screenshot taken on Wed Nov 23 16:07:12 2022 UTC)

The video shows a woman placing wrenches of different sizes on the bare skin of her arm and chest. The wrenches appear to stick to the skin. The video opens with the woman noting in French, “No glue,” but viewers never see the backsides of the wrenches that go into direct contact with the skin. The video does not provide any additional information about whether preparations were made before the recording.

Though the dialogue is partly covered by music, French-speaking Lead Stories staff could hear no discussion of a COVID-19 vaccine or a PCR test.

There is another scientific explanation, too, but it does not involve magnetism, either.

The Encyclopedia Britannica defines magnetism as:

[a] phenomenon associated with magnetic fields, which arise from the motion of electric charges.

That occurs in some metals, including iron, nickel and steel. However, COVID-19 vaccines do not contain metals or traces of them. Thus, the shots cannot give people any additional magnetic powers.

PCR tests have been widely used throughout the pandemic to determine whether a person has been infected with the coronavirus or not. However, this technique does not involve any injections. Instead, it does the opposite by removing a tiny sample of a person’s mucus or saliva:

The testing process begins when healthcare workers collect samples using a nasal swab or saliva tube.

Therefore, the act of testing cannot alter the properties of a human body in any way.

A scientific explanation of the phenomenon observed in the video rests on two natural laws: the force of friction and the act of balance.

The latter explains why metal objects may appear to be glued to the skin if one places them, for example, on a half-bent arm. The former, the force of friction, gives a more detailed understanding of how some people may appear to be “magnetic” without having this quality.

A physics textbook posted on the website of the University of Iowa says:

Friction is a force that opposes relative motion between systems in contact.

If two systems are in contact and moving relative to one another, then the friction between them is called kinetic friction. For example, friction slows a hockey puck sliding on ice. But when objects are stationary, static friction can act between them; the static friction is usually greater than the kinetic friction between the objects.

In other words, when one places a still object with a relatively flat surface (e.g. a metal spoon) on the skin instead of rubbing it against it, the static friction may hold them together if there is enough surface area to interact between them.

Liquids such as water and oil can change how objects behave toward each other. For example, the right amount may increase the interaction area without making the spoon slide down.

Human bodies naturally produce sebum, an “oily, waxy substance” protecting the skin. When people with oilier skin place metal items on their open body parts, those objects may stick to the skin. The same effect may be achieved if a person applies some oily cream to their skin. In the first seconds of the video, the woman is shown rubbing her arm.

Had it been real magnetism, it would work through the clothes as it works through a piece of paper when we attach a postcard to the fridge using a magnet. But it doesn’t.

If there were a magnetic field around the woman as she attaches objects to her skin, that could have been easily verified by showing the needle of a compass rotating like in the case of an actual magnet located nearby. However, there is no compass in the video.

Additionally, the application of baby powder that does not affect the magnetic qualities of metals will nullify what is perceived as a “magnetic” effect in humans resulting from oil on the skin, as shown here. The trick will not work effectively on hairy body parts because hairs decrease the surface of interaction.

Cases of real magnetism in humans are extremely rare, and involve foreign objects under the skin, as Lead Stories explained in a 2021 fact check:

In 2011 a doctor wrote up a case report about using an ordinary magnet to find a piece of metal which had somehow become embedded under his patient’s skin. The article, published by Reuters with the title “Metal under the skin? Find it with a magnet: doctor” includes a dramatic photo of the magnet pulling at something under the skin. In contrast, the videos circulating on social media do not show anything of the sort, not even the slightest tug of resistance at the skin’s surface.

Just like similar videos about vaccine-related “magnetism,” the TikTok clip doesn’t demonstrate that metal objects make the skin pull toward them.

Lead Stories has debunked numerous posts falsely claiming that COVID-19 vaccines and tests contain substances other than regulated, approved medical ingredients. Those fact checks can be seen here.

Other Lead Stories fact checks about COVID-19 can be found here.