Grief and conspiracy collide in Russia’s ‘Council of Mothers and Wives’

When Vladimir Putin announced the partial mobilization of reservists to bolster his war in Ukraine, thousands of people of fighting age fled the country. Protests broke out on the streets, and on the internet. For a brief moment, it appeared Russia might begin to see a unified anti-war movement.

But just like at the start of the invasion, physical resistance to mobilization soon began to fade. Russian resistance to the war today is mostly an online operation, and Telegram has become its central platform. With Facebook and Instagram banned under an “extremism” law, and Russian social media giant VK under almost direct control of the Kremlin, Telegram has offered a relatively safe harbor where one can find Russians expressing grief, anger and frustration about the war. But this comes right alongside political narratives and disinformation from across the spectrum and plenty of tall tales from the twisted world of conspiracy theories. It is from these foundations that an organization called the Council of Mothers and Wives has sprung into existence.

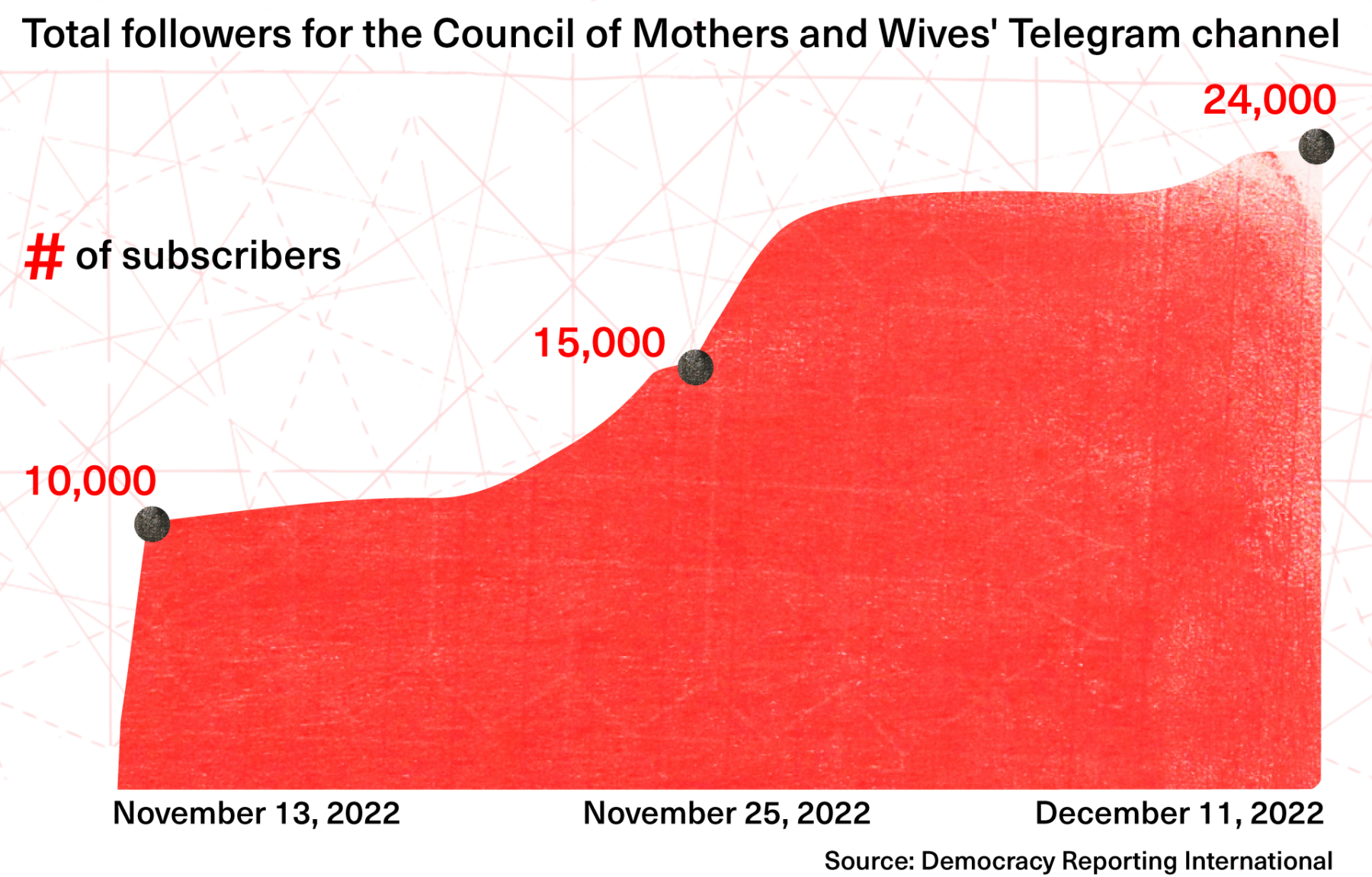

The Council launched its Telegram channel on September 29, just days after Putin instituted the partial draft, and now has more than 23,000 followers. Behind it is Olga Tsukanova, a 46-year-old mother who had a brief moment in the limelight when a video she posted on VK went viral. In the video, Tsukanova spoke of how her son was pressured on two separate occasions to sign a contract to be “voluntarily” sent to the front. “I address all Russian mothers,” she said into the camera. “Stop winding snot on your fist and crying into your pillow. Let’s band together.” After her video touched the hearts of mothers across the country, she decided to create the Council.

When I first sat down to read through the channel, I found testimony about conditions on the front and stories of families’ difficult experiences after their loved ones were drafted. In its second post, the Council demanded practical information about the deployment: How much training would draftees receive? What winter clothing would they be issued? How would food be organized? All were reasonable demands, given the news that Russian troops were hugely under-equipped for war. Pictures of supporters across the country, mailing their demands to the authorities, right up to the office of President Putin, followed.

But then another side of the channel began to emerge. Again and again, when I clicked through the links shared, I found myself on the page of another organization, the National Union of the Revival of Russia (OSVR). Established in 2019 to restore “the destroyed state of the USSR,” the OSVR looks longingly at the bygone days of the Soviet Union. It also fosters conspiracy theories on the coronavirus and 5G. According to the OSVR’s manifesto on partial mobilization, which was shared by the Council on Telegram, the war in Ukraine was “started by Chabad adherents” to build a “new Khazaria” on the territory of Russia and Ukraine — an antisemitic conspiracy theory that is grounded in the geography of the medieval Khazar empire and has prospered since the invasion. The OSVR is led by Svetlana Lada-Rus, a conspiracy theorist who believes that a third force is committing atrocities in Ukraine and has claimed that dangerous reptiles from the planet Nibiru would fly to earth and unleash chaos.

The OSVR’s influence on the Council is not an accident. Tsukanova spoke at an OSVR meeting in October and was a member of the now-defunct Volya party that Lada-Rus once led. Tsukanova told a reporter from Novaya Gazeta that the OSVR helped her to create the Council: “A lot of effort is needed for this, without the support of like-minded people, it is difficult to do this. The movement itself supported me.” Both women hail from Samara, a small city near Russia’s border with Kazakhstan.

“Internationally there has been a slight misinterpretation, or at least a superficial understanding, of this [Council] movement that is not to be confused with the more long-standing Soldiers’ Mothers of Russia,” Jaroslava Barbieri, a doctoral researcher on Russia at Birmingham University, told me. “If you look at Olga Tsukanova’s social media prior to the announced [partial] mobilization there is not so much talk about the so-called military operation, actually you will find content about conspiracy theories, a rogue government,” she said. “That is a bit more emblematic of a broader political stance of the members of this Council of Mothers and Wives.”

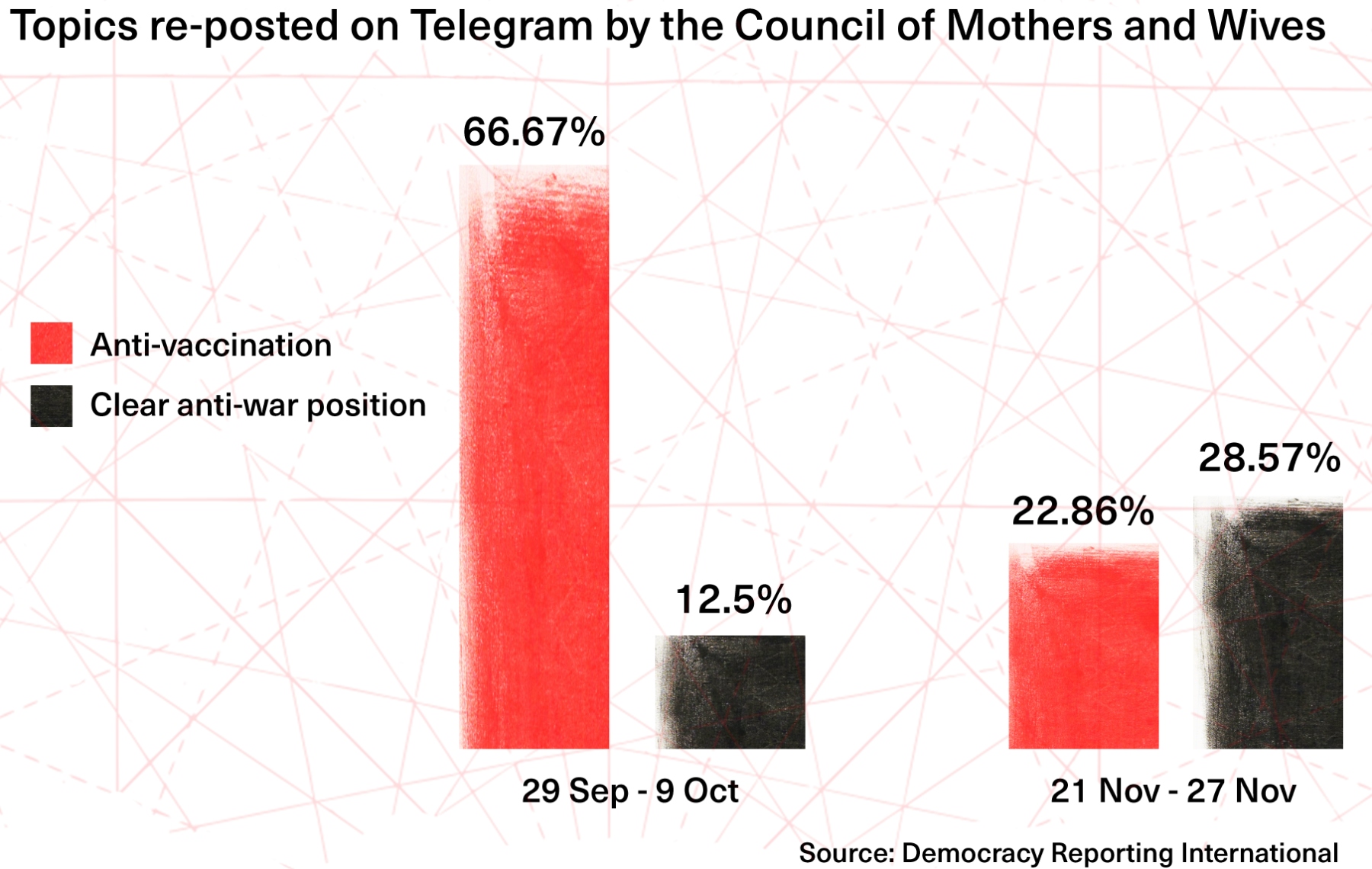

In addition to promoting OSVR materials, the channel also features a not-so-healthy dose of anti-vax propaganda. Coda Story’s partners at Democracy Reporting International ran an analysis of the channel and found that more anti-vaccination content was reposted in the first week and a half of its existence than content that could be described as clearly anti-war.

This peculiar cocktail of quackery, conspiracy and seemingly genuine grief about the war maintained a steady beat until mid-November, when the Council staged a public demonstration. On November 14 and 15, 2022, members of the group picketed the Western Military District headquarters in St. Petersburg where they demanded the return of mobilized troops from the Belgorod region near the border with Ukraine. Eager to get media attention, the group stressed on their Telegram channel that “no anti-war statements” were made, only a wish to open “dialogue with officials” about “specific shortcomings.” After the event, the Council got some national media coverage, which they hailed as a success.

Several days later, Putin announced plans to meet with a select group of soldiers’ mothers on the outskirts of Moscow. Handpicked for their association with pro-war NGOs, or for their outright support of the so-called special military operation, these were the women the Kremlin wanted to use to calm fears around mobilization. “This is a sensitive topic for [Putin],” said Maxim Alyukov, a research fellow at the King’s College Russia Institute. “The government perceives this issue of mothers and wives as a more dangerous issue than some kinds of political criticism, because it is something which can resonate with the public, and that’s why [the Kremlin] ran their own council of mothers and wives,” he told me.

For Tsukanova and her followers, the roundtable was a snub. They duly took to social media to air their grievances. “[Putin] wants to declare real mothers and wives extremists and agents. CIA?”, one Telegram post read. International media also took note. The BBC ran clips of Tsukanova saying that the Russian authorities were “absolutely” afraid of women. Democracy Reporting International’s modeling for Coda Story shows that, in the midst of these events, the Council’s Telegram channel saw a significant increase in followers.

Soon, the Council’s VK page was blocked on orders from the Prosecutor General’s office and a car carrying Tsukanova was stopped in Samara under the pretext of a drug search while the passengers were questioned. But while thousands have been arrested for their anti-war activism, and others subjected to exile, the Council has been able to continue its work weaving concerns about mobilization with the world of conspiracies. Pro-Kremlin media have been quick to point out links to the OSVR, and Russia’s pro-government, anti-cult organizations have also taken pains to call out the Council and accuse them of being provocateurs. The Center for Religious Studies, led by Alexander Dvorkin, also accused the OSVR of being financed by Poland and Ukraine, a common tactic used to undermine anti-war individuals and groups in Russia.

For Jakub Kalensky, a senior analyst at the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats, criticism from these corners is not surprising. “This might be very beneficial for you [as the Kremlin], if you have an anti-mobilization organization that is headed by questionable characters,” said Kalensky. “You can use their background to discredit the anti-mobilization position as a whole, this is a hypothesis we could work with,” he told me.

In this landscape, Russia’s anti-war activism has become ever more fragmented. Years of authoritarian rule have hollowed out the country’s civil society and stripped people of the ability to express dissent without serious repercussions. More than 2,300 people have been arrested in anti-war street protests since the partial mobilization was announced. In March 2022, legislation was introduced imposing prison sentences of up to 15 years for spreading “fake news” about the so-called special military operation. The war has only made the stakes higher, no matter which side you’re on.

Motivations for subscribing to Telegram channels undoubtedly vary — from a desire to stop mobilization to an outright anti-war, anti-Putin position. Groups that gain traction are quickly branded as extremist by the authorities. Those that aren’t often attract suspicion as having some nefarious link to the FSB, Russia’s security service. “There has been a history of infiltration of different opposition movements by the FSB either directly by speaking to members of those movements or most probably trying to send different messages to make them less appealing to different audiences,” Kasia Kaczmarska, a lecturer in politics and international relations at Edinburgh University, said. “This can sometimes work via multiple channels which the FSB is capable of organizing.”

“It’s important to highlight these more complex networks and the processes of how certain institutions came about, to not conflate them with genuine anti-war movements,” Barbieri, the Birmingham University doctoral researcher, added. “We also need to start thinking about how these disinformation narratives could also work as a coping mechanism for people so as not to face the reality of how the war in Ukraine began.”

Meanwhile the Council of Mothers and Wives continues to grow. As the full-scale invasion approaches its one-year anniversary, the channel blasts out condemnations of the mobilization alongside the wholesale promotion of conspiracy theories. It’s clear that the channel offers solace for some people, a place to vent their frustrations with a war they didn’t want in their lives. But for its leaders, it may be better understood as a vehicle for bringing an organization on the fringes of society to a new, and much more influential, audience.

This story was produced in partnership with Democracy Reporting International