How Republicans Are Echoing Climate Change Conspiracy Theories

Climate change denial is nothing new, and nor is criticism of policies designed to address it. However, as even previous opponents increasingly accept the scientific consensus, those still skeptical of global warming have turned to a new weapon to voice their disapproval.

They are increasingly embracing political rhetoric echoing conspiracy theories that global warming is a hoax by world leaders designed to subdue or impoverish their populations.

Largely—but not exclusively—confined to the right of the Republican Party in national politics, this kind of language centers on several key themes, such as the so-called “new world order,” “globalist politicians,” and “government control.”

While such claims may not stand up to scrutiny, how effective is such language in rousing popular support against climate change policies? Newsweek has spoken to experts in climate change policy and communication, who have charted what might lie behind it, and where it might be going next.

‘Climate Change Is a Globalist Agenda To Control People’

Getty

One assertion is that concerns about climate change and policies aimed to curb it are part of a global agenda designed to control people’s choices and limit their freedom. Some conservative Republicans are increasingly tapping into this kind of language.

Dan Bishop, a North Carolina GOP congressman, wrote in July 2022 that “Biden’s ‘climate crisis’ is just the latest excuse for the Left to abuse executive power to push an anti-American, anti-freedom agenda.”

Georgia representative Marjorie Taylor Greene has said the Green New Deal and “climate lies” are a “SCAM that waste trillions of taxpayers’ dollars and only serves the Liberal World Order enriching Klaus Schwab and those like his [World Economic Forum] frat boys.”

Colorado representative Lauren Boebert has said that policies like the Green New Deal and the Paris Agreement “work for globalist career politicians but they do not work for everyday Americans.”

Andy Biggs, a congressman for Arizona, said in September 2022 that California was “essentially imposing climate change lockdowns,” adding: “This is all about control (again).”

For him, the Green New Deal was “yet another power grab” even as “government control never leads to anything good.”

Newsweek has contacted Bishop, Greene, Boebert, and Biggs for comment.

While such criticism is often apparently based on genuine fears for people’s jobs or excessive government regulation, the language echoes conspiracy theories about climate change. These theories often center around the notion that policies to tackle global warming represent a mechanism for control.

For example, a post promoted by the Redpill Project, an online conspiracy theory outlet, described climate change as “just a scare tactic” and a “long-term justification to enforce the agenda.” It also claimed: “There have been carbon footprint scores/measurements assigned to EVERYTHING, even children and the number of them a family has. What a way to control population!”

The post appears to perpetuate one of the most common conspiracy tropes surrounding the growing global population and the impact it is having on the planet. The world’s population is expected to peak at around 10.4 million in the 2080s, the U.N. estimates.

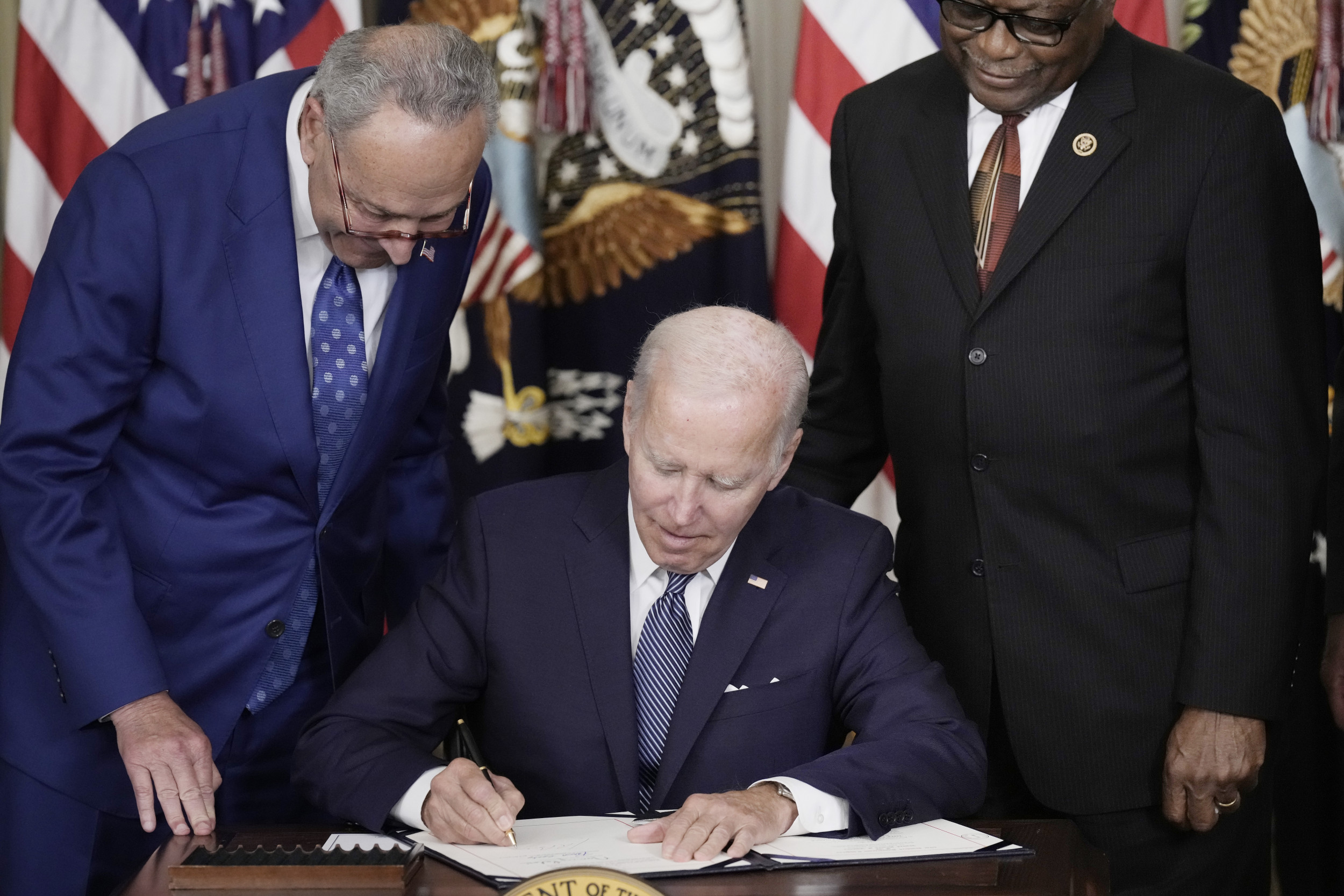

‘America First’

Win McNamee/Getty Images

“Most sort of climate change skeptics and deniers represent climate change not necessarily as a made-up story, but rather as an exaggerated story, which has been exaggerated by the so-called liberals in order to legitimize a big state controlling everybody,” Tim Forsyth, a professor in environment and politics at the London School of Economics, told Newsweek.

“It’s all to do with one’s attitude to regulation and rules, rather than necessarily whether the facts about climate change are believable or not.”

However, Forsyth noted that those on the left who want to see more state intervention on other issues, such as social welfare or women’s rights, “will also coalesce around true claims about climate change, because that’s also a convenient way to make the point about the need to do something.”

For Barry Rabe, a professor of public policy and environment at the University of Michigan, the claim is a reaction to the U.S. not being able to resolve the issue on its own, often having to be just one voice among many nations.

“It also collides with what I would call a kind of energy nationalism in the United States,” he told Newsweek. “That the U.S. is kind of an island: it can produce lots of energy, and largely set its own course. And so why are you going to worry about these relationships?”

Rabe agreed that the kind of language increasingly used, on both sides of the political spectrum, echoes an appeal to American isolationism.

“It’s sort of reflected in some of the more nationalistic or even America First rhetoric we’ve seen in recent years—and really, within both parties,” he said. “Even things like the Inflation Reduction Act are designed to encourage development and investment within the United States, as opposed to sharing resources or wealth and new technology with other nations.”

The antithesis is a “hard political sell,” Rabe said, as one of the “huge challenges” of climate change was trying to sell near-term actions for which the benefits will only be seen in the long term.

Forsyth said discussions about climate change were being “twisted” to address “older, tribal debates” to engage people in the issue. Any viewpoint tended to translate climate issues “into languages and themes which pre-exist and which people are more worried about.”

In terms of confronting rhetoric about a globalist agenda, Rabe said he did not want to defend “fancy conferences at Davos.” However, he said that polling suggested “growing numbers of Americans recognize this as a significant problem.” When it comes to a solution, “do you want the U.S. to just sort of sit on the sidelines, or hide from the rest of the world—or do you want it to engage constructively?”

A poll by the Pew Research Center in May 2022 found there was broad agreement on several specific policies to address climate change, such as planting more trees to absorb carbon emissions and offering tax credits for companies to develop carbon capture and storage technology. Both policies were backed by a majority of Republicans and Democrats alike.

However, President Joe Biden’s approach to climate change has proved far more polarizing, with 79 percent of Democrats saying it is taking the country in the right direction, and 82 percent of Republicans saying it is taking the country in the wrong direction.

‘Climate Legislation Is Aimed at Limiting Freedom and Culling Jobs’

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Echoing fears about population control is not the only rhetorical device that climate change deniers or skeptics are using. Another narrative increasingly used by those skeptical of the current administration’s approach to climate change connects the “new world order” with fears for Americans’ financial security.

According to the Redpill Project, in a “new world order” apparently being sought by Biden among others, environmental metrics “will affect [people’s] employability, credit worthiness, as well as other constitutional rights.”

Lawyers have indeed questioned the constitutionality of these metrics. However, their effect on creditworthiness is limited to companies and, according to one study, they actually improve employee satisfaction.

A January 27 blog post by the free market e-newsletter Economic Prism—reposted by the libertarian news site Zero Hedge, among others—states that in a “centrally planned economy, decisions are not made between individuals” but “by politicians and bureaucrats through policies of mass market intervention.”

“The elites pass down their edicts,” it added. “‘Thou shall not use gas burning stoves,’ for example. Or ‘thou shall burn corn in their gas tank.’”

To some extent, this politicization of the climate change debate, and the language around it, sees reactions split firmly along partisan lines. The notion of a political elite eroding people’s freedoms is frequently repeated.

Greene wrote in December that the “climate cult […] will force you to drive an [electric vehicle].” In February 2022 she said Americans “want to buy whatever kind of vehicle they decide without politicians telling them what they can and can’t buy. They want freedom.” Greene added: “They want Comrade Uncle Sam to stay out of their vehicle purchasing options.”

The Pew polling from May 2022 showed a majority of Americans are in favor of electric vehicle incentives.

‘Job-Killing Executive Orders’

Rhetoric around threats to people’s jobs—whether those fears are justified or not—also echoes and repeats certain key narratives.

The Pew polling shows a narrow majority of Americans, 53 percent, say stricter environmental controls are worth the cost, compared with 45 percent who say they will cost too many jobs and harm the economy.

However, the proportion of those who are worried about the cost of such policies is rising on both sides of the political spectrum, up by 12 percentage points since 2019. This includes about three-quarters of Republicans.

These genuine fears are reflected in the kind of language some Republicans are using, which often touches on certain key phrases.

“Biden’s relentless insistence to go green will stop nothing short of seizing control of your home thermostats,” Boebert wrote in September 2022. In 2021, she claimed that 10 million jobs were “at risk as a result of Biden’s job-killing executive orders.”

Biggs and Paul Gosar, an Arizona congressman, have said various climate-related policies will “kill American jobs.” Bishop wrote that the “far left expects you to lay your job down at the altar of climate change.” Newsweek has contacted Gosar for comment.

There is some basis for such fears, at least in certain industries. According to a World Economic Forum report, globally 3 million jobs will be lost because of the transition to greener economies by 2030, although these will be offset by the 13 million jobs the renewables sector will create. Researchers have also suggested that climate policy is less likely to have an impact on the fossil fuels sector than market responses to cheaper natural gas alternatives.

Forsyth said it nonetheless illustrated how debates about the climate are “twisted according to older worries, older debates, and therefore get distorted.”

Alex Wong/Getty Images

In the U.S., there have already been “significant shifts” in the energy sector from coal to natural gas and renewables, Rabe said.

“With that comes both economic disruption, but also some really significant economic opportunities,” he added. “So the challenge becomes taking advantage of those emerging developing technologies, where the U.S. has so much capacity, and building on it to try to really develop a more robust and diversified economy going forward.”

Speaking from Detroit—”where tens of thousands of people’s livelihoods are based on internal combustion engines”—he said that, understandably, part of resistance to the transition came from “those who see themselves as losers in this,” and there was uncertainty about how the transition to a green economy will be managed.

Mark Maslin, professor of earth system sciences at University College London, noted that there are around 10 million people employed in the U.S. green economy, compared with around 40,000 in coal.

“So if you want to boost employment and you want people to be happy, you boost the green economy,” he said.

Forsyth argued that scientific reports on climate focus on how it is changing, and conversations about how to improve the economy and retain jobs “need to sing through more loudly,” as climate deniers or skeptics seek to “stop that debate from happening or frame it in ways which already point to the outcome they want.”