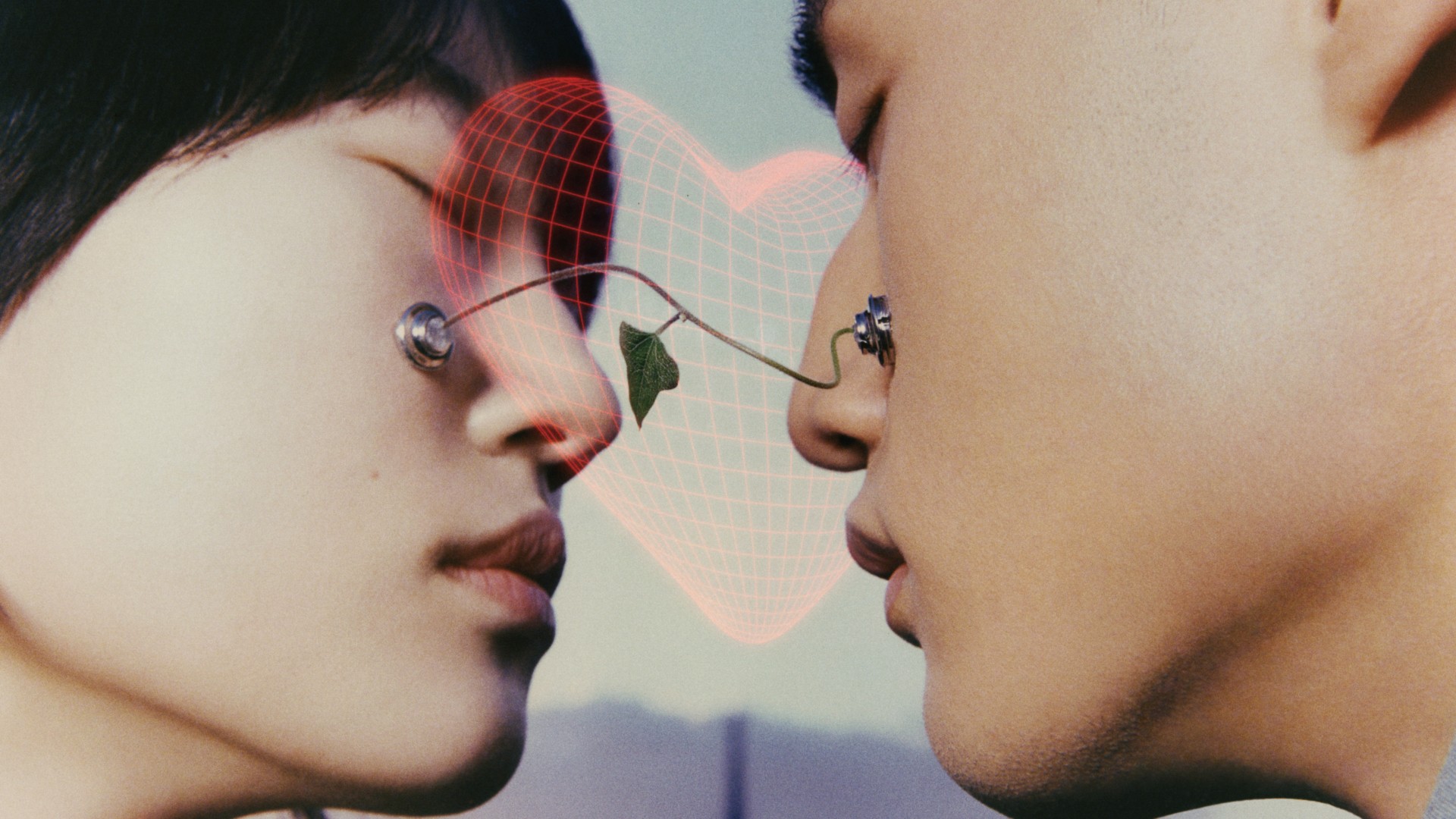

Climate Love (And Lies) on Dating Apps

Roses are red, violets are blue, can I talk about climate change denial with you?

Tinder is the Instagram of casual sex, short-term flings, as well as the promise of long-term love. And as with any self-declarative venture, dating apps like Tinder, Bumble, and Hinge welcome users to articulate their values either in their bios or on their profiles, so that possible matches can know what they stand for right away.

In an increasingly polarized world, shared values matter—especially when it comes to finding a potential mate. Someone with a badge declaring “Stop Asian Hate,” “Environmentalism,” “Vaccinated,” and “My Body My Choice” might do well to scroll past someone whose opening photo is them flexing their state’s right to openly carry firearms. Conversely, the language in someone’s Tinder bio or the cultural savvy in their prompt-selection on Hinge can help garner interest from like-minded individuals. Badges and catchy bios make it easy to judge a book by its cover, and in a fast-paced, scroll-centered world, these apps are designed to encourage just that.

These buzzwords and phrases can act as a sort of “fishing rod” with prospective matches in that they signal a similar sense of humor or a shared understanding of niche cultural references, according to Dr. Siân Brooke, a researcher in computational social science at the London School of Economics whose work covers self-representation on dating apps among other topics. In keeping with Dr. Brooke’s analogy, a person might cast a line out about, say, veganism as a form of climate activism, and any tugs on said line are likely to be from people who are either vegans themselves or who respect the practice.

There are chances of a third possibility, however, where someone swipes with more contrarian intentions. Unlike social media and chat forums where a person can post about their beliefs without a guaranteed response, dating apps offer a more direct route to private, one-on-one conversations, in turn attracting those who want to mansplain that the presence of winter storms negates the possibility of global warming. And the number of people who believe in conspiracy theories isn’t small: 60% of Britons say they believe in conspiracy theories, while 40% of Americans are sure of a secret group of world rulers. It’s why the last few years have seen the launch of dating apps like The Right Stuff or Awake Dating designed with conservatives and conspiracy theorists in mind.

But according to Dr. Brooke, many users still offer up one liners, such as “the Earth is flat” or, “9/11 was an inside job,” on mainstream dating sites in the hope of finding someone who agrees. And if it doesn’t land? “They have a get-out-of-jail-card,” Dr. Brooke says. “All they have to say is, ‘Oh, I’m just joking! Don’t you get it?’” But then, of course, there are the folks who aren’t kidding at all.

60% of Britons say they believe in conspiracy theories, while 40% of Americans are sure of a secret group of world rulers.

Liana DeMasi

Christa, aged 30, wears their heart on their sleeve in her Tinder bio—and with good reason. Part of her bio states they’re a “queer fat afab nonbinary ENM/polyamorous leftist.” Their decision to be forward about those intersectionalities is a matter of both pride and safety. “I am pretty open about my intersecting identities and that I’m progressive in my profile,” Christa told Atmos. “I have no interest in discussing anything with people who hold views that want to see my intersectional identities not… alive.” Like many others who are open about their values, beliefs or identities on dating apps, Christa assumed their bio would ward off any folks with significantly different views. So, when she matched with a climate change denier and conspiracy theorist, she was caught off guard.

“I don’t necessarily recall if he had [his political views] in his profile,” Christa said, calling attention to information that can be easily missed if you’re swiping too quickly. “But I do remember [that] our conversation started with him commenting on my profile and my politics.” He went on to tell her that the climate crisis was “less stressful than the media made it out to be,” and that chemtrails were to blame. The chemtrails conspiracy suggests that the contrails—those white, puffy streaks of water vapor and soot left behind by planes that have crystallized into ice at high altitudes—are actually government-funded methods of social control. Folks who follow this conspiracy believe that chemtrails are responsible for everything: from mind and population control to the spread of COVID-19 to climate change. The theory on the latter is that planes are releasing chemicals to purposely trap heat in the atmosphere in order to simulate a fake climate crisis that would increase government control over all aspects of our lives, from driving our cars to the legal size of our carbon footprint. (It’s true that planes are harming the planet with the amount of carbon dioxide they pump into the atmosphere, but crucially humans are worsening a climate crisis that, according to 97% of scientists, is in fact, real.)

Dr. Brooke is clear that the insistence on truth hiding in plain sight is a symptom of an even broader psychological phenomena: the pursuit and presentation of intellectual superiority. Climate deniers and those who engage in conspiracy theories generally have this air about them that Dr. Brooke describes as: “Aren’t you a bit stupid if you think the world is just as it appears?” Their emphatic belief in climate conspiracy theories push forward the idea that they know more than climate change scientists, activists, or believers; that they’re reading between the lines to see the subliminal truth.

“Media personalities like Joe Rogan, Jordan Peterson, and Andrew Tate talk about how climate change isn’t real, and then in the same breath, they talk about gendered romantic relationships.”

Dr. Siân Brooke

researcher, London School of Economics

It’s not that the interest in conspiracy theories is completely unfounded. The government has lied time and again. Consider the Bush Administration in 2002 stating there was “no doubt” Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction, or President Barack Obama pretending to drink the water in Flint, Michigan in 2016. Another example is how the U.S. government and Big Oil did in fact hide the truth about climate change in order to channel more money into fossil fuel infrastructure among other factors. Distrust in the government is legitimate, but when independent scientists, weather patterns, and climate disasters are all pointing toward the Anthropocene, it’s hard to ignore the facts. Of course, some folks still do, and this kind of rhetoric makes for a precarious online dating experience for those on the receiving end of declarations that the Earth is flat.

But what if you’re aware that conspiracy beliefs aren’t attractive in popular dating spaces? Take Justin, aged 26, who was raised a climate denier to think that most citizens were “brainwashed sheeple,” a fate that he was able to overcome through education and distance from his family. Now, Justin lives in New York City, where his first job out of college was in the green energy sector. No longer under the thumb of his father, he was able to see the truth for what it was, but previously he was on dating apps as a conspiracy theorist—albeit with a degree of self-awareness. “I just knew not to talk about it,” Justin says. “Unpopular opinions are going to be unpopular, and I had no interest in shoving my own [perceived] intellectual superiority down someone else’s throat.”

It’s possible that the acknowledgement of one’s beliefs as unpopular might spark a kind of introspection that could lead to the truth. But it could also drive one to a community that’s built on those “unpopular” lies, validating them and normalizing them to the point of truth. The latter is not uncommon. High-profile personalities like Joe Rogan, Jordan Peterson, and Andrew Tate have built whole personas and amassed millions of followers for being mouthpieces for contrarian theories. “[These media personalities] talk about how climate change isn’t real, and then in the same breath, they talk about gender roles, dating, and gendered romantic relationships,” Dr. Brooke says, referencing Tate’s frequent mentions that “women belong to men,” and Rogan and Peterson’s conversations surrounding climate denial and the “crisis in masculinity.” This rhetoric positions misogyny at the core of many conspiracy theories and internet movements, a growing number of which are related to climate denial.

It goes without saying that those who aren’t already climate change skeptics are likely to find conspiracy theories and their rhetoric a turn-off—rather than a turn-on. Even so, the potential harm of spreading lies on topics related to the climate crisis and environmental justice cannot be understated, especially as the world struggles to grapple with the consequences of more frequent natural disasters and instances of extreme weather year on year. Despite the facts, it seems that, when Mother Earth is considered, some climate change deniers would much rather swipe left.

The image by Cho Gi Seok first appeared in Beyond the Human as part of Atmos Voume 06: Beyond.

Keep Reading

60 Seconds on Earth,Anthropocene,Art & Culture,Climate Migration,Black Liberation,Changemakers,Democracy,Environmental Justice,Photography,Earth Sounds,Deep Ecology,Indigeneity,Queer Ecology,Ethical Fashion,Ocean Life,Climate Solutions,The Frontline,The Overview,Biodiversity,Future of Food,Identity & Community,Movement Building,Science & Nature,Well Being,