Why conspiracy theorists and the Kremlin echo each other’s disinformation

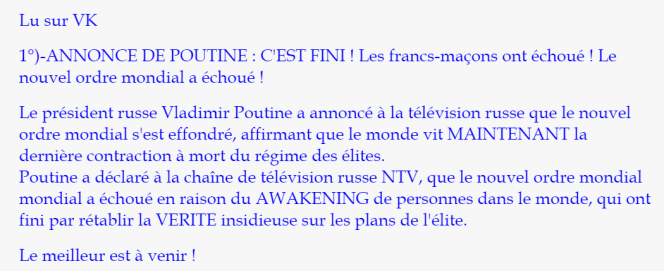

“Look at what they’re doing with their own people!” In his address to the nation on February 21, Vladimir Putin accused the West of having made pedophilia “the norm.” A wild attack typical of the Kremlin leader, but one which resonated with the most far-out conspiracy circles, such as the QAnon community which spreads disinformation about pedophile elites in the White House.

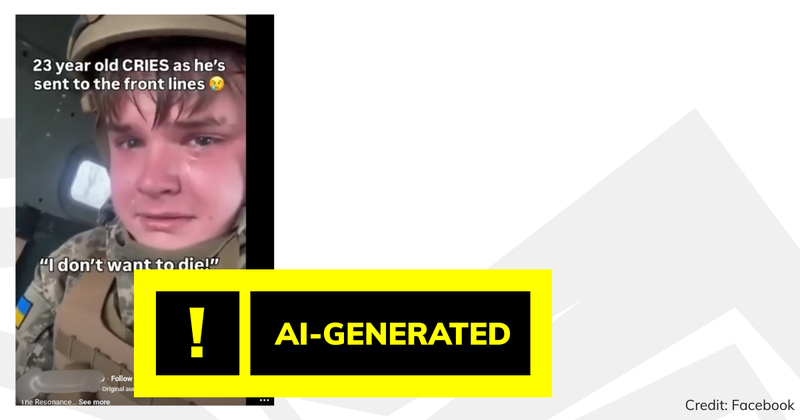

This was just one of many such claims, along with the denunciation of the alleged “Ukronazis,” rumors of American biological weapons hidden in Ukraine, and accusations of staging every massacre of civilians by the Russian army. For the past year, since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, there are only a few delirious notions that have not been taken up by either the Kremlin’s influencers or Western conspiracy theorists.

The convergence has reached the point where the two circles now feed each other, in an incessant back and forth. “What is difficult,” observed Pierre-André Taguieff, political scientist and author of several books on conspiracy, “is to distinguish between propaganda manufactured by Kremlin strategists and the multitude of Russian and French conspiracy circles that gravitate to them and can be manipulated.”

Dredged up by the Kremlin

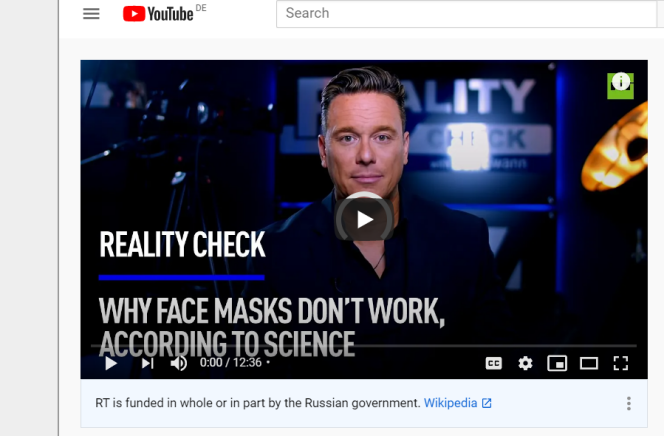

Putin’s Russia has long been attracting communities of protesters convinced of a conspiracy, particularly through its state media, RT and Sputnik, since the annexation of South Ossetia in 2008. “RT was already distributing Russian disinformation and networking the conspiracy scene, even though it was less structured than today,” noted Rudy Reichstadt, founder and director of the Conspiracy Watch website.

Since then, true to their motto “Dare to question,” Russian state media have cozied up to France’s Yellow Vest protestors, and then to Covid skeptics during the pandemic. A report by the Russian investigative website in exile Meduza showed that in 2021 RT adapted its message to each specific country, even if that meant expressing opposing views.

Its editor-in-chief, Margarita Simonyan, called Russian vaccine skeptics “anti-vax morons” and “murderous fools” while promoting anti-vaccine activists and conspiracy theorists in its foreign editions. The conspiracy influencers returned the favor, largely defending Russia since the beginning of its invasion of Ukraine.

This is good news for Moscow, which knows the value of amplifying local dissident voices. “It is essential to use as much as possible fragments of segments by the popular Fox News host Tucker Carlson,” a memo to the Russian media recommended in March 2022. The memo was published by the online news magazine Mother Jones, and went on to note that Carlson “sharply criticizes the actions of the United States [and] NATO,” and the “defiantly provocative behavior from the leadership of Western countries and NATO towards the Russian Federation and towards President Putin, personally.”

A statement in line with the Kremlin’s narrative. “The idea that the Western world is plotting against Russia is a constant theme of Russian propaganda,” Taguieff commented. But it is better served when it is an American or French voice that expresses it.

The strategy of Soviet ‘sharp power’

Although it is not the only one to do so, Russian diplomacy has a long tradition of stirring up foreign public opinion. As early as the end of the 19th century, the Czarist government had an office for publishing false articles in the Parisian press, as historian Andrei Kozovoï writes in Les services secrets russes: des tsars à Poutine (“The Russian secret service: From Tsars to Putin”, 2020).

During the Soviet era, the USSR financed the publication of several books attributing the assassination of J. F. Kennedy to an American conspiracy, and then, in the 1980s, spread the rumor that HIV was an artificial virus created by the United States. Behind this subversive approach is a strategy that international relations researchers now call “sharp power,” a venomous counterpoint to the more benevolent and sunny “soft power.”

“When you can’t subjugate people using the appeal of your own model, you have to undermine the allegiance of the citizens [of foreign countries] to their own system,” Rudy Reichstadt explained. And the conspiracy scene, this machine for hating existing elites and democratic institutions, is a perfect channel.

Seen in this way, the novelty lies less in the originality of the process than in the scale and systematization of the phenomenon, facilitated by the polarization of political life, the acceleration of transmission of information through social media, and the possibility of easily flooding these sites. In 2018, Twitter identified nine million tweets linked to Russian disinformation, while in the fall of 2022, Facebook announced the dismantling of two Russian and Chinese disinformation networks.

A shared worldview

However, to reduce the Kremlin to a simple manipulative agent would be to miss the fact that, like conspiracy theorists themselves, the highest Russian authorities maintain an ambivalent relationship with the paranoid theories they disseminate. “You have to understand that before using a theory for strategic purposes, the Russian political-military elites are often convinced of its veracity,” confirmed Dimitri Minic, a specialist in Russian military thought and researcher at the French Institute of International Relations (IFRI). “For example, it has happened that the KGB itself fabricated evidence of conspiracies, while not doubting for a moment their existence, although they were still too well hidden, as they thought.”

Conspiracy theories and fake documents are common in Russian political and military literature, like with one of the most influential Russian ideologists today, the ultranationalist Alexander Dugin. “He is both a conspiracy theorist and a conspiracy theoretician – he believes in a number of conspiracy narratives,” Taguieff emphasized.

Even at the highest level of the Russian government, the synergy with conspiracy communities is deeper than it seems. Like them, Putin shows disgust for sexual minorities, often presented as perversion or pedophilia. He expresses the same rejection of the Atlantic policy, perceived as threatening and warlike. Finally, he relies on the same mystical reading of the way the world works, which is threatened by “Satanism.” The term didn’t originate from a QAnon fan or Kremlin troll but from Putin himself.