Adam Selzer: Conspiracy theories have long been part of Chicago politics. Consider the 1899 mayoral election.

Wild conspiracy theories have always been a part of elections. Hours after this year’s Chicago mayoral election ended, talking heads on fringe cable channels were claiming that a “cartel” of teachers would be using voter fraud to elect Brandon Johnson. Ubiquitous boogeyman George Soros was said to be bankrolling them.

But this has always been a part of politics, and nothing this year is likely to approach the levels of absurdity seen in our mayoral election of 1899.

Advertisement

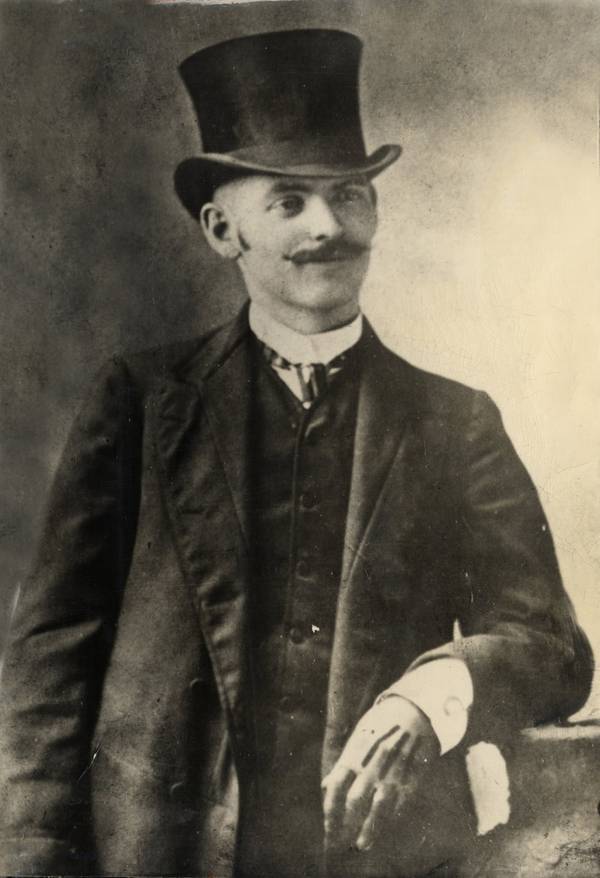

That spring, the incumbent Carter Henry Harrison Jr. squared off against Sanitary Board member Zina Carter, with former Gov. John Altgeld as a third-party spoiler. The Chicago Daily Inter Ocean’s coverage made Harrison sound like a regular Batman villain, with daily stories accusing him of fraud, blackmail, kidnapping and even murder, all aided by men with names like Nobby Clark, Cocoanut Morrisey, and Tommy the Clock. For a week, their pages were dominated by headlines that screamed “Murder For Harrison,” “Mayor’s Thugs Riot,” “Vice and Crime Reign” and “Shall the Scum Triumph?”

The most important part of Harrison’s “evil plan,” they said, was to “colonize” the levee district with thousands of imported vagabonds, pickpockets, tramps and thieves who would vote for him illegally. Most of this would be paid for by extracting ever steeper “assessments” from “every all-night saloon, gambling hell, policy shop, swindling museum, lottery shop, house of ill-fame, thieves’ resort, massage parlor, opium den, assignation-house, poolroom, and low dive in the city.” Other fundraisers took the form of secret orgies held by “the offscourings of society.”

Advertisement

As mayor, Harrison was famously lenient on the city’s vice districts and really was supported by notorious Aldermen “Bathhouse John” Coughlin and “Hinky Dink” Kenna. But the Inter Ocean ran daily lists of other “harpies” of crime and vice it claimed were part of Harrison’s cabal — men with names such as Sly Teddy, Ugly Pat, Knocker O’Fallon, Sixteen Mule Pete, Kid Roach, Seven-Up Jim, Sassy Bill, Lumpy Johnson, Farmer Brown and the Medicine Kid.

During the week before the election, hardly any crime was committed that the Inter Ocean couldn’t tie to Harrison. When James Kinahan, a minor underworld character, was killed in a shootout on Wabash Avenue, it was minor news in most papers. The Inter Ocean insisted on its front page that Kinahan had been murdered — on Harrison’s orders — due to rumors that he’d squealed about the “colonization” plot to the newspaper’s reporters.

Days later, a Wilmette constable was found dead at Hotel Bremer, a victim of poisoned wine administered by two women who’d lured him there to rob him. The Inter Ocean blamed that on Harrison too. “The Harrisonian carnival of crime produced its daily victim yesterday,” they wrote. “Hard pressed by the extortion of the Harrison campaign managers, the criminal classes are driven to desperate straits to pay the required blood money and live.”

Of course, elections in those days always got a little bit rowdy. When the election board met to revise the voter rolls, there were fistfights in the corridors of City Hall. One man, Richard Hardiman, claimed that Coughlin had choked him. Coughlin was briefly arrested, and when Inter Ocean reporters couldn’t find Hardiman, they asserted that his friends “never expect to see him alive.”

When Harrison won the election handily, the Inter Ocean simply claimed that it had thwarted his fraud attempts, so he’d won fair and square, after all. Its coverage of the various killings and beat-downs it had pinned on him largely stopped. It only briefly mentioned that Hardiman had turned up alive.

All papers openly backed one candidate or another, and most made a few accusations of electoral shenanigans, but none of the others came close to the Inter Ocean’s level of sensationalism. Indeed, the Inter Ocean itself had been known as an upscale, literate paper for most of its existence. It hadn’t covered an election this way before and never would again.

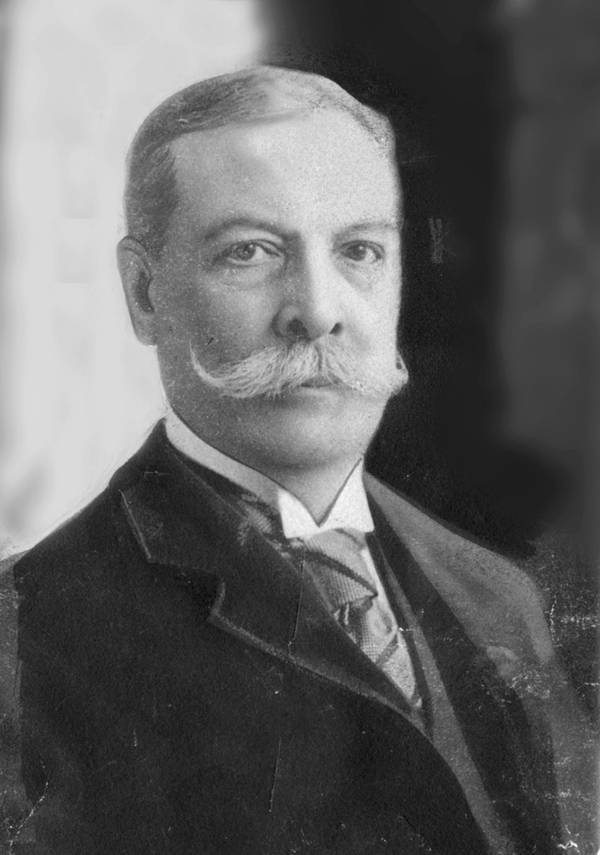

The reason for its anti-Harrison fervor was personal. In late 1897, the paper had been bought by financier Charles Tyson Yerkes. His franchise on using the city streets for his street cars and tracks was set to expire soon, and besides using the paper as his own personal bullhorn, he was using bribes, blackmail and every other dirty trick at his disposable to get a 50-year extension. Yerkes believed that slow, overcrowded cars were the most profitable, and Chicagoans loved to hate him.

Harrison knew that letting “Baron Yerkes steal the streets,” as he put it, could cost him his job, and he opposed the extension, even though Yerkes bluntly asked him how much of a bribe he wanted. Coughlin and Kenna were offered cash for their support as well, but they decided that staying on the mayor’s good side would be more profitable in the long run. The franchise extension ordinance was crushed just a few months before the election. In the Inter Ocean’s breathless claims that Harrison would force criminals to rob and kill every decent person in Chicago, Yerkes was simply engaging in petty revenge.

Advertisement

Most of the outlaws the paper named had never been mentioned in the press before and never would again. With the newspaper tasked by the boss with being as inflammatory as possible, one can imagine that a couple of reporters probably had a lot of fun dreaming up those nicknames. They probably assumed that no reasonable person would believe the stories anyway.

If conspiracymongers must make up wild stories about Johnson and Vallas this year, can they at least throw in some characters like Kid Roach and Tommy the Clock?

Adam Selzer is a historian, tour guide and author of the recently published book “Graceland Cemetery: Chicago Stories, Symbols, and Secrets.”

Submit a letter, of no more than 400 words, to the editor here or email letters@chicagotribune.com.

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from Chicago Tribune can be found here.