What to do when someone you love gets sucked into conspiracy theories

Tanya’s* brother had always been interested in outlandish theories and legends – mostly harmless stuff like “aliens and abandoned cities”, she says. But during the 2020 lockdown, he went from perusing random urban myths to wholeheartedly believing a range of Covid-related conspiracies.

“He would still wear a mask, but thought it was a form of control,” Tanya recalls. “He once showed me a video of a guy from New Zealand talking about nanobots being put in medical masks. The idea was essentially that Covid nose swabs would compromise the blood-brain barrier, and the nanobots in the mask would then be able crawl from the mask up through your nose and get to your brain.”

“I, of course, find it ridiculous and want to laugh at it all,” Tanya says. “But it is worrying how much he really believes it.”

Conspiracy theories are nothing new. In ancient Rome, many believed that the emperor Nero, who committed suicide in 68 AD, had actually faked his own death and was in hiding, plotting his return to power. In the aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot in 1605, some suggested that the whole thing was fake, masterminded by the Secretary of State, Robert Cecil, to make King James I look powerful and whip up hatred for Catholics. In the late 60s, there was a popular theory that Paul McCartney had died in a car crash in 1966 and was subsequently replaced by a lookalike, with the surviving Beatles weaving clues that the real Paul was dead into their albums.

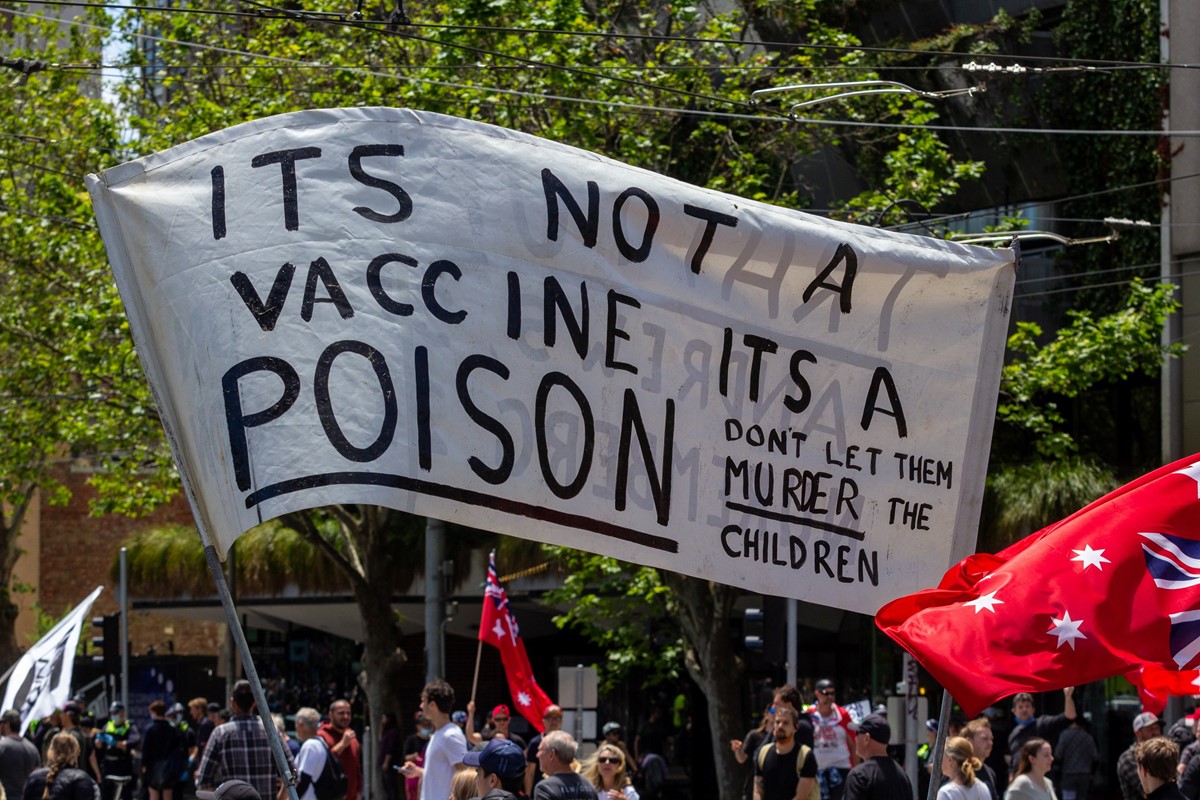

In recent years, however, it seems as though conspiracy theories are popping up with alarming frequency. Climate change is a hoax, a satanic paedophile ring is running the world, the powers that be are poisoning us all via chemtrails. Perhaps most obviously, there were a number of theories that spread in 2020 during the pandemic: some thought the lockdown was a government ploy to arbitrarily restrict our freedom, some thought the vaccine was actually implanting microchips in people, some, like Tanya’s brother, thought that masks contained nanobots. Some thought all of these things.

Dr Daniel Jolley is a social psychologist whose research focuses on the psychology of conspiracy theories. “People are attracted to conspiracy theories in an attempt to satisfy three psychological needs. They want more certainty, to feel in control, and maintain a positive image of their self and group,” he explains. “During times of crisis, such as the COVID pandemic or rapid political change, these needs are more frustrated and people’s desire to make sense of the world becomes more urgent. In essence, people believe in conspiracy theories to make sense of a complex and changing world.”

“During times of crisis, such as the COVID pandemic or rapid political change […] people’s desire to make sense of the world becomes more urgent” – Dr Daniel Jolley

He adds that while social media has allowed conspiracies to spread further and faster than ever before – he says the shift is like witnessing “conspiracy theories on steroids” – it’s likely that only those who find these theories and start believing in them are “already susceptible” to doing so. Evidence backs this up, and thankfully, belief in conspiracy theories is not on the rise. Instead, it’s more likely that the small minority of people who do believe in them are incredibly vocal, and are able to share their opinions more widely since the advent of social media. “These same people may have hunted for such explanations for world events, even without the internet placing the explanations at their fingertips,” he says. “So [conspiracy theories] certainly appear more popular and they spread quickly, but evidence suggests that beliefs have remained the same.”

Even so, the fact remains that the number of people who do believe in conspiracies is still worryingly high (one in five Brits believe Covid was deliberately created and spread by the Chinese government). It’s easy to be dismissive of conspiracy theory believers – especially when so many are so ridiculous – but worryingly, conspiracy theories appear to be developing an ever-more dangerous, harmful edge. Much of the misinformation circulating today seems to push people towards political extremes or incite hatred towards marginalised groups such as the LGBTQ+ community. And while it was probably a bit grating for Paul McCartney to have to continually affirm that, yes, he was actually alive, nobody died as a result of the ‘Paul is dead’ theory – but people did die for believing the Covid vaccine contained formaldehyde; we will all die if we don’t start taking climate change seriously.

Ultimately, it’s worth trying to talk people round if they start talking about how Bill Gates is tracking their every move, rather than merely rolling your eyes at them. “These conversations are difficult, but they are crucial. It will likely need to occur over a period, where the trust and conversation builds,” Dr Jolley continues. “But these conversations are needed to ensure that the individual can feel that they are part of a community. In essence, reassure the person if they feel uncertain, make them feel more in control if they are worried or powerless, and help them make social connections if they feel isolated.”

“I really miss my brother sometimes. It literally feels like he is a different person when he goes off on a tangent” – Tanya

It can be especially confusing, painful, and maddening when a loved one gets sucked in by misinformation, as Tanya found out firsthand. Ben* also tells me his mother began to believe in conspiracy theories at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020. “It was when the death toll went up by thousands every day – she just didn’t believe it. She watched something on TV where a funeral director said he’d quit his job because they were putting deaths down as caused by Covid when they weren’t,” he recalls (there is ample evidence that Covid death counts have not been inflated). “She also thinks the vaccines aren’t there to help you get better, they’re there to kill you or harm you.”

“This impacted me a lot,” Ben continues. “She was constantly watching things on her phone, on the internet, constantly going on about it to me. It was very stressful, very frustrating.” Tanya had a similar experience with her brother. “It makes me not want to pick up the phone most of the time, because it is very draining and boring to hear about,” she says. “It honestly makes my whole body deflate if he starts speaking about anything conspiracy-related […] I wish he just dropped it so we could have a normal catch-up, as I really miss my brother sometimes. It literally feels like he is a different person when he goes off on a tangent.”

Evidently, it’s not always as simple as blocking and ignoring that Twitter guy who keeps posting “fake news!!!” under news stories about climate change. Sometimes that person is your dad or your best friend. Or, in Tanya’s case, it was her sibling; in Ben’s case, his mum. And when it comes to speaking to a loved one about conspiracies, Dr Jolley has some sage advice. “Conversations with those who believe in conspiracy theories are difficult. However, there are some conversation starters that could be useful,” he says.

“First, take an open-minded approach, which starts with asking questions and listening. You want to build understanding with that person. Second, be receptive and seek to build a connection,” he says. “Third, affirm the values around critical thinking, such as redirecting critical evaluation skills towards a deeper examination of the conspiracy belief – such as encouraging them to consider all pieces of evidence. Fourth, you encourage a much forward-focused approach and inspire them to think about areas of their life that they have control.”

There’s no quick trick to coax someone out of a rabbit hole, and it’s imperative you keep calm and patient throughout the process – Dr Jolley says it’s vital to use an “empathic, understanding, and open-minded approach”. And as frustrating as these conversations can be, it’s also important to lose hope. “Conspiracy theories can impact the smooth running of societies, from impacting vaccine uptake and climate action to inspiring violent reactions,” Dr Jolley adds. “Developing interventions that can tackle the negative consequences of conspiracy theories is an important endeavour.”

Basically, when it comes to challenging conspiracy theorists in your personal life: listen to their concerns, be patient with them, and above all, don’t give up.

*Name has been changed