Q&A on RSV Vaccine Candidates for Older Adults

This year, the Food and Drug Administration will consider several applications for vaccines and a monoclonal antibody to prevent respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, illness. The common virus causes a mild cold in most people, but infants and older adults can experience serious and dangerous illness.

The vaccines and preventive antibody are aimed at those populations.

As we reported last fall, an early surge of RSV infections led to full capacity at children’s hospitals across the country, so the disease — and finding a way to prevent it — may be top of mind for many parents of young children. But the pursuit of a safe and effective vaccine has been decades in the making, and the recent promising candidates are due to a scientific breakthrough in researching how the virus infects cells.

While these medical products have not been approved by the FDA yet — and we can’t say exactly when or whether they will be — they are moving through the application process. If greenlighted, they could be available for the next RSV season this fall.

Dr. William Schaffner, medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases and a professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, told us that with these candidates, we’re “on the threshold of being able to really make an impact on RSV both in infancy and in adults.”

We’ll go through some common questions about RSV and the potential vaccines for older adults in this story. In a second article, we’ll address the vaccine candidates for pregnant people, and the monoclonal antibody candidate for infants.

What is RSV?

RSV causes cold-like symptoms, including runny nose, coughing, sneezing, fever, wheezing and loss of appetite, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infants younger than 6 months may only exhibit difficulty breathing, irritability and a reduction in activity or appetite.

It’s typically a colder-weather virus, circulating in the fall and winter.

Throughout a lifetime, a person can be reinfected with RSV “quite often,” Dr. H. Keipp Talbot, an infectious diseases expert at Vanderbilt University, said during a presentation on RSV immunity before the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee on Feb. 28. The committee — VRBPAC for short — met over two days to discuss two vaccine candidates for older adults.

Immunity acquired from an infection “does not provide durable or complete protection from reinfection,” Talbot, who is also a member of an advisory committee to the CDC, concluded, after explaining the research from several studies. Another case of RSV can occur within two months of a person’s last infection.

For most people, the disease is mild, and they’ll recover within two weeks. But infants and older adults, particularly those with heart and lung disease, weakened immune systems, or premature and young babies are at higher risk of developing a severe infection and needing to be hospitalized.

Schaffner told us there’s a need for a lot of education on the virus and that’s particularly the case for the risks for older adults. He said the vast majority of physicians caring for older adults were taught that RSV is a pediatric virus and information on the impact on the older adult population developed over the last 10 to 15 years.

For adults age 65 and older, the CDC estimates, based on a several studies and its own surveillance data, that there are 60,000 to 160,000 hospitalizations due to RSV per year and between 6,000 and 10,000 deaths. Dr. Fiona Havers, the lead of the CDC’s hospitalization surveillance team for coronaviruses and respiratory diseases, presented this data at the Feb. 28 VRBPAC meeting, noting that the wide ranges show there’s “substantial uncertainty” about the disease burden and that the upper ranges could be higher, because RSV testing isn’t often done.

For comparison, influenza is associated with 128,000 to 467,000 hospitalizations and 16,000 to 43,000 deaths each year among adults 65 and older, according to the CDC.

There isn’t a “quick, accurate and relatively inexpensive” RSV test for use in doctors’ offices, Schaffner said. Testing is mostly done in research studies and in hospitals, where it’s expensive and done as part of a test looking for multiple viruses at the same time.

Havers said those 80 and older have much higher rates of hospitalizations for RSV, at 237 to 325 hospitalizations per 100,000 people, three to nearly four times higher than the rates for 65- to 69-year-olds, according to the CDC data, which relies on information from a network of hospitals in 12 states.

Why are there several potential vaccines now?

Scientists have been working on vaccines for RSV for decades.

In the 1960s, a clinical trial testing an RSV vaccine for infants made with inactivated virus — the same method used for the flu and hepatitis A vaccines — found that it didn’t stop infections, and vaccine recipients had more severe illness when they later contracted RSV than infants in the control group. Two infants, ages 14 and 16 months, died.

It wasn’t until scientific research published in the journal Science in 2013 that the outlook for viable RSV vaccines changed considerably. A team of scientists at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which is part of the National Institutes of Health, were able to stabilize the pre-fusion form of the virus’s F protein — the protein the virus uses to enter human cells — and determined through animal testing that immunization with variants of this pre-fusion F protein sparked highly protective antibody responses.

A December 2021 Nature story explains that the F protein changes its configuration once it fuses with cells into a post-fusion form. But targeting the pre-fusion, and less stable, form — as opposed to the post-fusion form — produced higher antibody responses, the researchers said in their 2013 study.

All of the vaccine candidates moving through the FDA approval process now target the pre-fusion F protein.

Dr. Alejandra Gurtman, Pfizer’s vice president of vaccine research and development, said during the VRBPAC meeting that the “ground-breaking structural work by the National Institute of Health elucidated that RSV F on the virus exists as an unstable pre-fusion form” — and only the pre-fusion form can bind to and enter a human cell. “Antibodies specific to the pre-fusion form are most effective at blocking virus infection,” she said, showing a graphic to illustrate how the pre-fusion F vaccine candidate produced about 50-fold higher RSV neutralizing antibodies in studies in primates than the historical candidates targeting the post-fusion F.

Some of the same scientists involved in the 2013 research on RSV similarly locked SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein into its pre-fusion form, laying the foundation for the development of the COVID-19 vaccines, as we’ve explained before.

What are the potential vaccines for older adults?

Pfizer and GSK have submitted applications to the FDA for their RSV vaccine candidates for adults ages 60 and older. These were the two vaccines discussed in the Feb. 28 and March 1 meetings of the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee.

Both vaccines are protein subunit vaccines — meaning they’re made from just a piece of the virus, in this case the stabilized RSV pre-fusion F protein. The pre-fusion F prompts an immune response but can’t cause RSV disease. The hepatitis B and pertussis vaccines are made in the same way.

Pfizer’s vaccine, called Abrysvo, employs pre-fusion F protein from RSV-A and RSV-B, subgroups of the virus. GSK’s vaccine, called Arexvy, combines the pre-fusion F from RSV-A with an adjuvant, a substance that can enhance the body’s immune response to the F protein. The adjuvant in the RSV vaccine candidate is the same, but a lower amount, as the one used in Shingrix, the shingles vaccine also produced by GSK.

Pfizer initially tested adding an adjuvant, but found “no substantial benefit” in immune response by including it, Gurtman said.

Moderna is also working on an RSV vaccine candidate for older adults, using mRNA technology, the same technology used in Moderna’s and Pfizer/BioNTech’s COVID-19 vaccines, to deliver instructions to cells to make the stabilized pre-fusion F protein to trigger an immune response. Moderna has said it will submit an application to the FDA in the first half of this year.

Janssen, a Johnson & Johnson company, is working on an RSV vaccine for older adults that also targets the pre-fusion F protein, using both bits of the protein and a harmless adenovirus to deliver instructions to cells to make their own protein. The latter is the same type of technology used in the J&J COVID-19 vaccine. A spokesperson for the company told us it was analyzing phase 3 trial data.

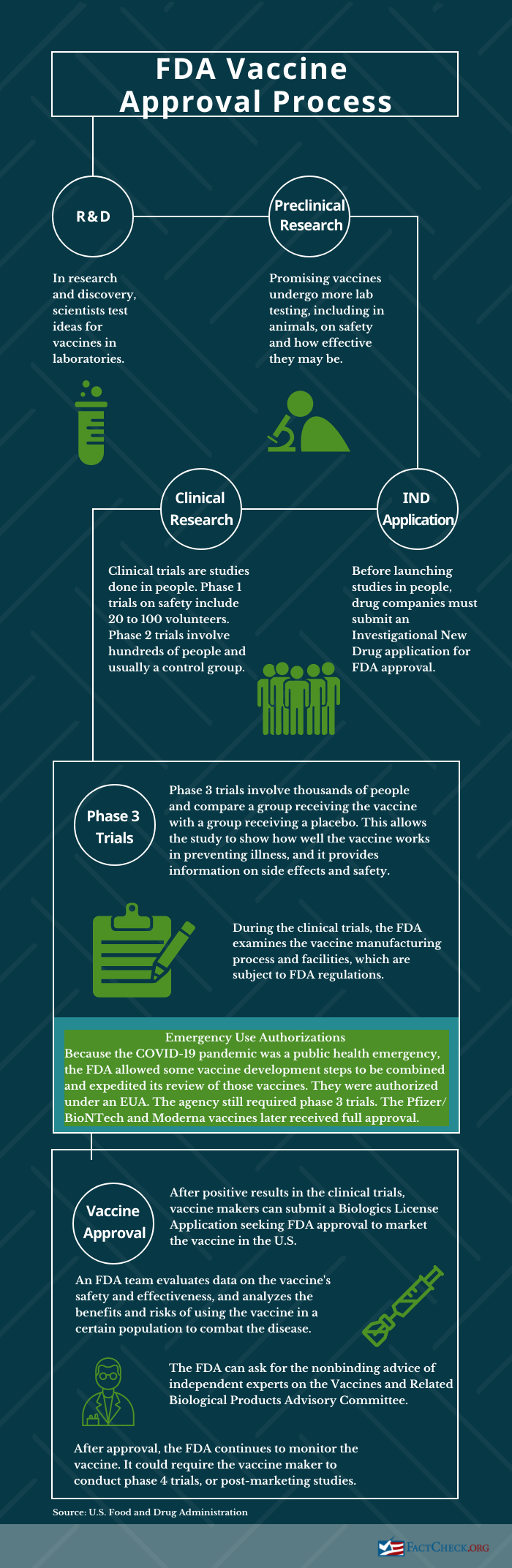

Where are they in the FDA approval process?

The independent VRBPAC experts voted that the clinical trial data supported the safety and effectiveness of the Pfizer and GSK vaccines to prevent lower respiratory tract disease caused by RSV in the 60 and older population. The votes on the Pfizer vaccine were 7-4 for both effectiveness and safety; the GSK vaccine garnered a unanimous 12-0 vote on effectiveness and 10-2 on safety.

The FDA doesn’t have to adhere to that vote in making its decision on whether to approve the vaccines. Both pharmaceutical companies say they expect a decision from the FDA in May; GSK specifically says a decision would come by May 3. If approved, the vaccines would be available for the next RSV season, starting in the fall.

Both of the applications, accepted by the FDA in November and December, are under “priority review,” which means the FDA aims to make a decision in six months, instead of the standard 10 months. The agency grants priority review for drugs that “if approved, would be significant improvements in the safety or effectiveness of the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions when compared to standard applications,” the FDA says. This doesn’t change the length of clinical trials or “the scientific/medical standard for approval or the quality of evidence necessary.”

Again, Moderna and Janssen haven’t yet submitted to the FDA for approval.

How effective are they?

We have the most information about the Pfizer and GSK vaccines that were discussed by VRBPAC, so we’ll concentrate on those. Both companies reported high efficacy in preventing lower respiratory tract illness symptoms due to RSV.

Efficacy is the relative reduction in a clinical trial in illness between the vaccinated and placebo groups. It represents a lower risk of getting sick if vaccinated.

Both companies presented trial data for one RSV season. This was the primary objective for the trials, but participants are being followed for two RSV seasons in the Pfizer study and three seasons in GSK’s. The trials are ongoing. That means the data for both companies do not yet cover the current RSV season, which saw a surge in cases and hospitalizations for older adults as well.

GSK told us it expects to have data on the second RSV season in the Northern Hemisphere in the third quarter of this year.

Pfizer. Results from the main Pfizer phase 3 clinical trial in adults age 60 and older, which began in 2021 and is ongoing, showed a vaccine efficacy of 85.7% in preventing at least three lower respiratory tract illness symptoms due to RSV, with two cases in the vaccine group and 14 in the placebo group through one RSV season, or at least six months. Efficacy in preventing at least two symptoms was 66.7%, with 11 cases in the vaccine group and 33 in the placebo. Pfizer hasn’t yet published these results in a peer-reviewed journal.

Lower respiratory tract illness symptoms included cough, sputum production, wheezing, shortness of breath and tachypnea, or rapid breathing.

The trial didn’t include enough severe illness cases — defined as lower respiratory tract illness symptoms requiring hospitalization, the administration of oxygen or mechanical ventilation — to provide an analysis on vaccine efficacy for severe disease. There were only two hospitalizations due to RSV in the trial, both in the placebo group.

The trial enrolled 34,284 people in the U.S., Canada, Finland, The Netherlands, South Africa, Argentina and Japan, with about half getting the vaccine and half getting a placebo. Participants were 60 to 97 years old, and 37.4% were 70 or older.

Pfizer said the participants were healthy or with “stable chronic conditions,” and the data show about half in both the vaccine and placebo groups had at least one high-risk condition, such as heart or lung disease, diabetes, or were smokers.

GSK. GSK’s phase 3 trial efficacy data — which has been published in the New England Journal of Medicine — showed a vaccine efficacy of 82.6% in preventing RSV-confirmed lower respiratory tract disease in adults age 60 and older, with seven cases in the vaccine group and 40 in the placebo group. The efficacy against severe disease was 94.1%, with one case in the vaccine group and 17 in the placebo.

The definition of lower respiratory tract disease was similar to Pfizer’s but slightly different. Lower respiratory tract disease was two or more symptoms or “signs,” the latter of which included wheezing, crackles, rapid breathing, low blood oxygen levels and supplemental oxygen. Severe disease was defined as at least two “signs” or an assessment by the trial investigator, or the patient needing mechanical ventilation. (See slide 27.)

The trial, which began in 2021, enrolled nearly 25,000 people in 17 countries, with half of them getting the vaccine and the rest getting a placebo. About 40% of participants were considered frail or “pre-frail,” based on a gait speed test, about 95% had at least one comorbidity and about 40% had a “comorbidity of interest” associated with severe RSV.

The efficacy in preventing RSV-confirmed lower respiratory tract disease in that population of interest was 94.6%, with one case in the vaccine group and 18 in the placebo, but there were too few cases in the frail population to determine efficacy in that group.

VRBPAC’s vote: Pfizer. The FDA advisory committee voted 7 to 4, with one abstention, in favor of the available data adequately supporting the effectiveness of Pfizer’s vaccine candidate in preventing RSV-caused lower respiratory tract disease for adults 60 and older. The experts who voted yes said that the primary outcome in the trial was met, though some noted that the trial didn’t provide evidence on the prevention of serious outcomes.

Those who voted no said they’d like to see the additional data yet to come for another RSV season, since the efficacy, thus far, was based on a relatively small number of cases — 44 total — with wide confidence intervals. As Dr. Jay M. Portnoy, a pediatrician at Kansas City’s Children’s Mercy Hospital who voted no, said, “One or two cases in the opposite direction could’ve change the results.”

A confidence interval is a statistical measure — in this case, a range of what the efficacy would be expected to be for the whole population.

There was also concern that the trial didn’t adequately study a high-risk population. Dr. Henry Bernstein, a professor of pediatrics at Hofstra University, said the vaccine should be created for the needs of “vulnerable populations, not healthy people.”

He said the efficacy against lower respiratory tract disease is “impressive,” but the vaccine “really didn’t do anything for hospitalization or death, which is one of the major things I suspect that we would want from a vaccine in protecting against or preventing respiratory disease.”

Some of those who voted no said they probably would be yes votes with the additional data to come.

VRBPAC’s vote: GSK. The advisory committee was unanimous — 12 to 0 — in saying the data supported the effectiveness of the GSK vaccine.

Several committee members noted that the data in the GSK trial were “a bit more representative of the population that’s really at risk of this disease” than the Pfizer trial, as Holly Janes, a biostatistics expert with the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, put it.

Portnoy said that while the efficacy data were similar to Pfizer’s, the confidence intervals were “narrower.”

Dr. Marie Griffin, a professor emerita at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, noted the unanimous vote would be seen as supporting the licensure of the vaccine, “and I don’t think necessarily everyone who voted yes thinks that the vaccine should be licensed at this point.” She said it was a “great study,” but “I would be more comfortable with … more years of data.”

Others echoed those comments. Dr. Stanley Perlman, a professor of microbiology, immunology and pediatrics at the University of Iowa, said he hopes the vaccine isn’t licensed for a year or two so that there are more data and “more comfort” with both safety and efficacy.

Dr. Amanda Cohn, with the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, added that in order to see the impact of the vaccine, a high percentage of older adults would need to get it. “It may be that having more robust data … that we will be getting soon may in the long run actually be better for public health than getting this vaccine out” in the upcoming RSV season.

Moderna and Janssen. We have more limited information on these candidates, since the companies haven’t submitted to the FDA for approval and VRBPAC hasn’t discussed them.

Moderna reported in January that in a phase 3 trial, its vaccine showed an efficacy of 83.7% against RSV-related lower respiratory tract disease, defined as at least two symptoms and that there were “no clinically significant safety signals identified.” For Janssen, positive results from a phase 2b trial on efficacy and safety in the over-65 population were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in February.

What do the safety data show?

Pfizer. The company said the data show its vaccine was “safe and well tolerated.” Reports of pain at the injection site were low — 10.6% among vaccine recipients — and other reactions including fatigue, headache, and muscle or joint pain were reported in low and similar percentages in the vaccine and placebo groups.

However, there were three serious adverse events that the FDA and the study investigator deemed to be “possibly related” to the vaccine: an allergic reaction or “hypersensitivity” within eight hours of vaccination; a case of Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare neurological disorder in which the immune system damages the nervous system; and a case of Miller Fisher syndrome, a variant of Guillain-Barré. The latter two conditions occurred in 66-year-olds, a man and a woman, about a week after vaccination.

While those are only two cases, given the number of trial participants, that translates to a Guillain-Barré case rate of about 1 in 9,000 people, much higher than the expected background rate of 1.5 to 3 cases per 100,000 people older than age 60 in the U.S. each year, the FDA said in its briefing document on the vaccine.

Guillain-Barré, often linked to a viral or bacterial infection, has been associated, rarely, with other vaccines, the CDC says. While the syndrome can lead to lasting nerve damage, most people recover.

There were no deaths in the trial deemed to be related to the vaccine, and the number of deaths in the vaccine group, 52, was similar to that in the placebo group, 49. Within one month of vaccination, there was an imbalance in atrial fibrillation events, or irregular heartbeat – 10 in the vaccine group and four in the placebo. The trial investigators didn’t consider any of those to be related to the vaccine. The FDA is reviewing those cases.

In an earlier, small trial in which some participants received the RSV vaccine and an influenza vaccine at the same time, Pfizer saw a trend in “decreased [immune] responses to the flu vaccine,” Gurtman said. The company is studying this in a larger trial.

GSK. The company said the data show the vaccine was “well tolerated” and had an “acceptable safety profile.” Pain at the injection site was the most common side effect reported; nearly 61% of a subset of participants who were solicited for such feedback reported injection-site pain. Fatigue, muscle aches, headache and joint stiffness were also reported at rates higher than the placebo group.

Fatalities were balanced between the vaccine and placebo groups.

There was one case of Guillain-Barré syndrome nine days after vaccination that was considered “to be related to vaccination” by the FDA and the study investigator, the FDA briefing document on the vaccine said. That would be a rate of 1 per 15,000 people. And there were two cases of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, or ADEM, a neurological disorder involving swelling in the brain and spinal cord, both in 71-year-olds in a smaller phase 3 trial, with 890 participants, studying co-administration with the flu vaccine.

In one of those cases, a man experienced symptoms seven days after vaccination and later died. The other case was a woman who experienced symptoms 22 days after vaccination and recovered. The study investigator said the cases were “possibly related” to the flu vaccine, and the FDA considered them to be “possibly related” to either the flu or the GSK vaccine.

There was also an imbalance in atrial fibrillation within 30 days of vaccination, with 10 cases in the vaccine group and four in the placebo. Dr. Peggy Webster, vice president and head of vaccine safety at GSK, said during the VRBPAC meeting that six of the cases in the vaccine group and two in placebo were in people with a history of the condition. As with the Pfizer vaccine, the FDA is reviewing those cases.

The FDA and the study investigator considered six other cases of potential immune-mediated diseases to be possibly related to the vaccine: gout, pancytopenia, Bell’s palsy, psoriasis and Graves’ disease. There was also a case of gout in the co-administration study, possibly related to the flu or GSK’s RSV vaccine, FDA said.

In the co-administration study, there is “no evidence for interference in immune responses” to the flu and GSK vaccine, FDA said.

VRBPAC’s vote: Pfizer. The VRBPAC vote on the Pfizer vaccine was 7-4, with one abstention, that the data supported the safety of the vaccine — but with only one committee member, Hofstra University’s Bernstein, voting no on both efficacy and safety.

Those who voted yes said the available data show the vaccine is safe, and more information on Guillain-Barré wouldn’t come through the clinical trial, but rather though post-approval surveillance, which would involve a lot more people getting the vaccine. The FDA has requested that Pfizer develop such a follow-up study. Some said that a potential co-administration issue with the flu vaccine was an implementation issue, not a safety issue for this vaccine.

The four no votes were concerned about Guillain-Barré and not having more data on co-administration with the flu vaccine.

Griffin, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, talked about safety in terms of benefit versus risk. She said she would be less concerned about the safety signal in a population that had a very high hospitalization risk, but that population was underrepresented in the trial. Given the Guillain-Barré concern, she said, the “benefit for relatively healthy older people … is not that great, compared to a possible high risk of a very severe outcome.”

Dr. Daniel Feikin, a respiratory disease consultant and a yes vote, said a Guillain-Barré safety signal is “potentially there.” But there were “only two cases,” which had “a potential other explanation for GBS.” Like other committee members, he said he didn’t think more data on this would be available except through a post-marketing, meaning after approval, follow-up study. While the phase 3 trial is following participants for two RSV seasons, the vaccination is only given before the first season.

Some of the experts expressed concern about potential vaccine hesitancy among the public, given the experience with the COVID-19 vaccines, particularly vaccination rates with the booster shots. Portnoy, who voted yes on the safety question, said before the vote: “I think we have to be really careful before we send the vaccine out to cover large groups of patients given the hesitancy that occurred surrounding COVID vaccine, which turned out to be a very safe vaccine.”

VRBPAC’s vote: GSK. The committee voted 10-2 that the data supported the safety of the vaccine.

Dr. Hana El Sahly, chair of the committee and a professor of molecular virology and microbiology at Baylor College of Medicine, and Griffin voted no due to concern over the ADEM and Guillain-Barré case rates. El Sahly said the inflammatory neurologic diagnoses “do rise above the average seen,” and while she agrees that post-marketing surveillance can help answer whether this is a true safety signal, “once a vaccine is licensed it is really hard to collect data given our decentralized health care delivery system. … Pre-licensure is probably where most of the effort should go when feasible.”

Griffin said the ADEM and GBS cases, versus two hospitalizations in the placebo group, made it “hard to weigh the risks and benefits,” and she also wanted to see more data on co-administering the vaccine with the flu vaccine and the COVID-19 vaccine, since that’s likely the way vaccination would be done in the public.

Perlman, who abstained on this question for Pfizer, said he was “a little more convinced” on the safety of the GSK vaccine, noting there was only one case of Guillain-Barré and that both ADEM cases occurred in South Africa among about 150 participants, raising questions about whether those were due to vaccination.

Bernstein, who had voted no on both questions for the Pfizer vaccine, also said “it’s just not clear whether or not there’s a true safety signal” with ADEM or atrial fibrillation and that post-marketing surveillance would be helpful in that regard. He added that he doesn’t think the vaccine needs to be rushed to market, “if in fact it’s at the expense” of the older population getting flu and COVID-19 shots.

Who would get them and how often?

It’s too soon to say. The Pfizer and GSK clinical trials don’t yet have data through a second RSV season to answer the question of how long vaccination would provide protection — though the VRBPAC members talked about it potentially being an annual vaccine, like the flu shot.

After the FDA approves vaccines for use, the CDC, drawing upon recommendations from its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, issues guidelines on who should get the vaccines and how frequently. However, RSV “work groups,” which include ACIP members, presented the available data on the Pfizer and GSK vaccines and information on RSV in a late February ACIP meeting. The work groups make recommendations to the entire ACIP, but then the work groups do not vote on the final guidance.

The majority opinion of the adult RSV work group was that both vaccines should be recommended for those 65 and older, but not those 60 to 64. Also, there was “a substantial minority opinion” not to recommend the vaccines based on the available data, the CDC’s Dr. Michael Melgar, the lead of the adult RSV work group, said, due to concern about risk-benefit balance and “underrepresentation” in the trials of adults older than 80 who are most at risk of severe illness from RSV.

A CDC spokesperson, Katherina Grusich, told us in an email that “[n]o votes were taken,” at the February ACIP meeting, “but the discussion – which included robust deliberation around available safety, cost and effectiveness data, and potential clinical considerations – will help inform future ACIP policy recommendations” if the vaccines are approved by the FDA.

Editor’s note: SciCheck’s articles correcting health misinformation are made possible by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The foundation has no control over FactCheck.org’s editorial decisions, and the views expressed in our articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundation.