Punch-ups at the polling booths! England goes to war over voter ID

LONDON — Canada, Italy, Norway, Israel and Hungary already demand it. France does too, but — naturellement — will let you use your hunting permit.

But Brits have never had to show photo ID in order to vote — until now.

Over the last 10 days, doormats across England have thudded to the arrival of 27.5 million polling letters, familiar missives alerting voters to annual local elections at the start of May.

This year’s letters, however, are twice the normal size — the extra space filled with instructions for voters to bring one of 22 listed forms of identification to their polling station, or be refused a ballot.

You may like

What sounds like a simple security step is proving hotly contentious in Westminster — and has left some election officials fearing mutiny, and even violence, at polling booths on May 4.

“Will it get a bit nasty? Hopefully not so nasty that punches are traded and police are called, but who’s to say?” said a concerned returning officer — the senior official running a local election — at one mid-sized council.

“There will be a proportion of voters who don’t behave reasonably — who might get angry about it, saying ‘I pay my U.K. taxes, I’ve been on the register for 40 years, you are denying my vote.’”

Tory ministers who introduced the new law insist voter ID is necessary to tackle perceived electoral fraud. But Labour’s deputy leader Angela Rayner has called it a “blatant attempt to rig democracy in the favour of the Conservative party.”

Like critics in those U.S. states that have introduced voter ID rules, opponents claim the laws “suppress” marginalized groups who are less likely to possess required documents. They note darkly that acceptable ID under Britain’s new rules includes pensioners’ bus passes, but not travel passes for young people, who are less likely to vote Conservative. Tories roundly dismiss such arguments, saying voter ID is backed by international election observers.

Both sides know the stakes are only going to get higher. Next month’s elections to fill 8,000 local council seats across England are essentially a trial run for the system ahead of a U.K.-wide general election next year.

All eyes will be on official figures to be published by the Electoral Commission watchdog as early as the summer, revealing how many voters were denied a ballot on May 4.

Fears of ‘irate’ voters

At the sharp end of the new laws will be polling station staff — local council workers who previously sat beside polling booths ticking off names on a register.

They will now be expected to compare each voter’s likeness to their documented photo, and decide if it’s similar enough to allow them to vote. Their duties will include asking women to remove religious headgear before one of 40,000 specially-purchased mirrors and privacy screens. A female official must be on hand at all polling stations.

“Everyone is resigned to delivering it, but a lot of people are very nervous about it,” said one senior public official who deals with multiple councils and returning officers across England.

Some voters will be “irate,” they predicted. “We hope the electorate are respectful of the fact that the staff are only doing their job. But this is another barrier that’s been put in the way … We just don’t know until we get there on polling day.”

Councils have extra funds to hire 20,000 more poll clerks, but are struggling to recruit them, the official said. Groups of local polling stations could even be combined into “hubs” to ease the burden, they suggested.

The cross-party Local Government Association (LGA), which represents local councils across the U.K., asked for the new system to be delayed.

Vince Maple, a Labour representative on the LGA Elections Task Group, said: “It’s quite clear that a number of councils are struggling with long-standing individuals who have given service in polling stations simply refusing to do so, because of the very changed role they will have to play.

“Some of the issues [for staff] are around not feeling it is the right approach. Some of it is around feeling unsafe.”

A U.K. government spokesperson said it was “working closely with the sector to support the rollout” and that Whitehall is “funding the necessary equipment and staffing for the change in requirements.”

ID-free since 1832

Though new to a whole generation of English voters, tussles over identity were commonplace before official electoral registers first began in 1832. Voters would tell the returning officer their name and might need to prove their age, property ownership, or whether they were in receipt of alms.

Opponents could then challenge their right to vote and present evidence, “with arguments dragging on for months,” said Matthew Grenby, of the Eighteenth-Century Political Participation & Electoral Culture project.

But until now there has never been a requirement to show picture ID — except in Northern Ireland, where photo ID was launched in 2003 to combat a “widely-perceived” notion that electoral abuse was a major issue.

Supporters point to that change, under Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair, as a success story. They say its launch in England will uphold electoral integrity and tackle the perception of fraud.

Critics brand it a sledgehammer to crack a nut, saying there were only 183 allegations of in-person fraud at a polling station between 2014 and 2022. Downing Street said it was guarding against “potential” wrongdoing.

The biggest objection is that nobody is sure how many voters lack the right ID — a figure estimated anywhere between 925,000 and 3.5 million.

People can apply for a ‘Voter Authority Certificate’, a free ID provided by councils. But only 50,000 people had done so as of this week, far below the number expected to apply in the scheme’s first year.

Applications are still ticking up, however, and by February 63 percent of people at least knew they needed ID, up from 22 percent in December. The LGA and government launched a joint push Thursday for people to apply for certificates “as soon as possible.”

But a “massive gap” remains ahead of an April 25 cut-off to apply, said Greg Stride of the Local Government Information Unit think tank. “Back office staff are thinking — if all these applications come in on the deadline, how are we possibly going to get through them in time?”

A spokesperson for the U.K. government insisted: “The vast majority of people already have a form of acceptable identification. We’re urging anyone who doesn’t to apply for a free Voter Authority Certificate as soon as possible.”

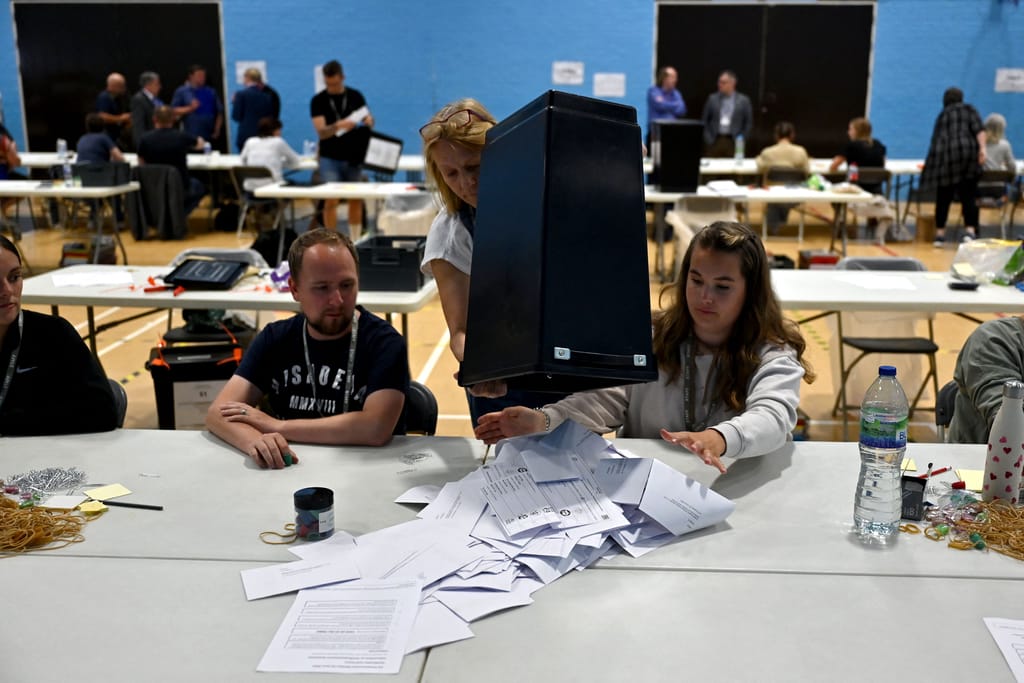

Results day

After the elections, campaigners’ focus will switch back to the U.K. Electoral Commission.

The watchdog is asking all 230 councils involved to record the number of voters they turn away for lacking ID, and the number of those who then fail to return later that day. In 10 pilot areas trialled in 2018 and 2019, the total was 740.

The commission will issue “initial analysis” in the weeks after May 4, followed by a full report in mid-September.

But there are questions about the quality of the data. Failed voters will only be recorded if they approach the desk inside a polling station, not if they retreat after seeing a poster by the door.

This is important in elections where council seats are sometimes tied, and won (and lost) on a coin toss.

Kevin Bentley, Tory leader of Essex County Council and an LGA executive member, said councils have “stepped up” in the circumstances, but warned: “Let’s say you lost by five votes, and five people were turned away … You didn’t know how they were going to vote, of course, but that could be an issue.”

Both anonymous officials quoted above said they did not expect widespread legal challenges, since “election petitions” cannot challenge the national law — only whether it was applied consistently. They must also be filed within 21 days.

Regardless of the outcome, Bentley said voter ID should be reviewed after May, in time for next year’s U.K. general election. “When you bring in a new system, whatever the subject, I think you need to evaluate it — did that go well, did it not?” he said.

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from POLITICO Europe can be found here.