He Ran the Pentagon’s UFO Unit—and Says the Government Is Withholding the Truth

The RV was parked inside a mouse-infested hangar at the edge of a horse pasture. It was a 38-footer—a plausible amount of space for Luis “Lue” Elizondo, his wife, Jen, and their two German shepherds, Hercules and Paris. But this was no KOA, with handy sewer and water lines.

The drinking water from the spigot made them both sick before they realized it was best left to the livestock. Every week or so, Elizondo humped out the 20-gallon black-water tank to dump into the sewage tank they’d put in the ground. There was no air conditioning, and flies were incessant. It was, in other words, not the kind of arrangement you’d expect for the star of a newly launched History Channel show. Still, Elizondo figured it wasn’t so bad, trudging across the pasture, sidestepping horse patties.

This was 2018, more than a decade after he’d served as a counterintelligence officer in Afghanistan under far more precarious conditions. Here in rural Southern California, the hazards were entirely of the mind. Elizondo had to embrace his decision to forgo his corner office at the Pentagon, with its steady and reliable paycheck; he had to avoid giving mental energy to vindictive employees within the Department of Defense who were furious about his departure and his new life in the public eye. In a nation both ravenous for and divided by conspiracy theories and pseudoscience, he had to block out threats and character attacks emanating from the nether regions of the internet. And he had to reassure Jen when she was perturbed with him, which was often, because more than two decades into their marriage she felt obligated to point out the ways in which their circumstances had taken challenging turns. Such as, most people don’t live 15 feet from their own waste.

Elizondo understood that this was on him. This was his self-appointed mission as a Pentagon whistleblower: to compel the U.S. government to own up to the public about what it knew—to share what he’d seen in his Pentagon days—about UFOs, which have been rebranded UAPs, or unidentified aerial phenomena. He viewed this as a necessary sacrifice.

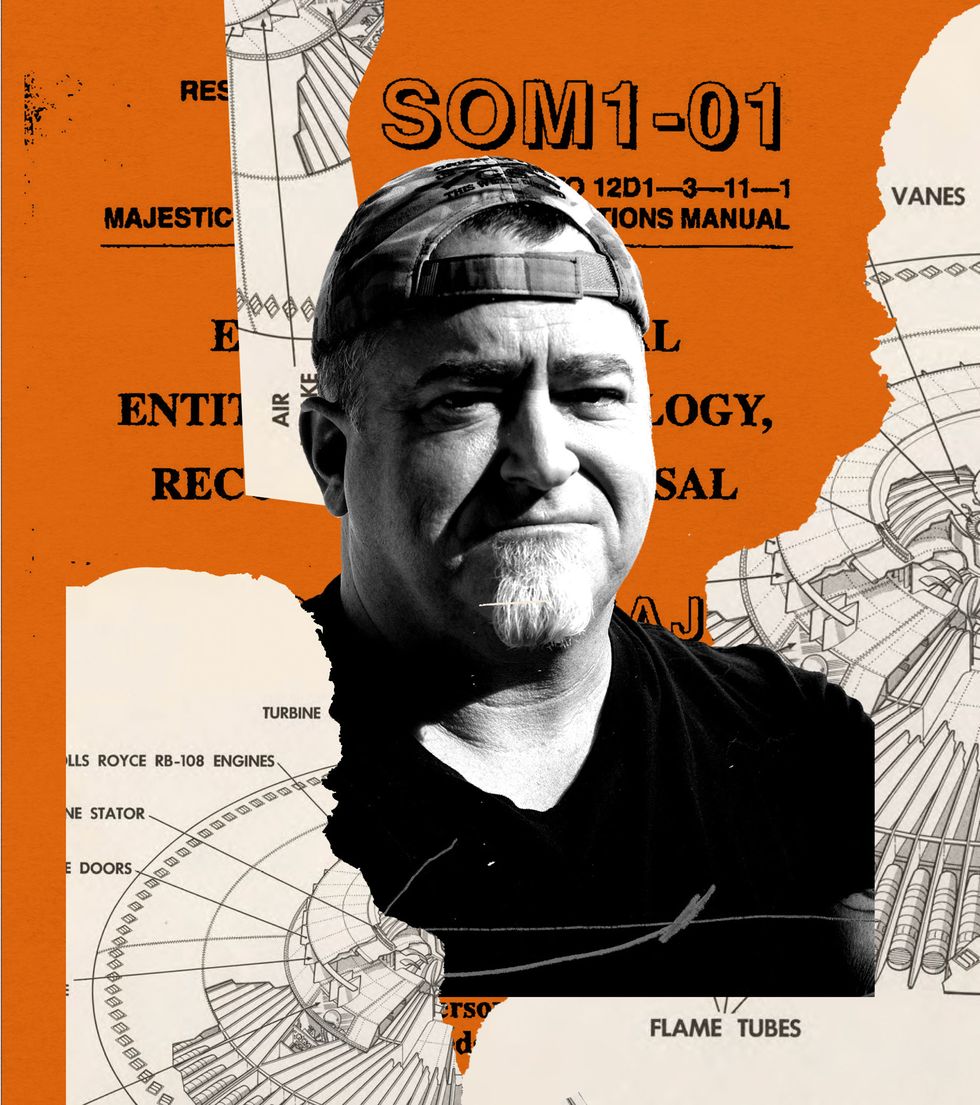

The irony was that to the outside world, it looked as if Elizondo had launched a glamorous new life, as if he had jettisoned an anonymous job deep in the folds of the military-industrial complex to launch his star turn in the infinite sunshine of California. He and his billy-goat soul patch were costarring on the TV series Unidentified: Inside America’s UFO Investigation. His name was on the front page of the New York Times. He was a talking head on cable news. He had triggered a bidding war for a UAP book that will highlight “profound implications for humanity,” according to his publisher, HarperCollins imprint William Morrow. He could be heard on a dozen different podcasts at once.

It seemed as if he had arrived—except that Elizondo had long operated in the shadows, and that was how he preferred it. He was doing all of this because it was the only way, as he saw it, to make people grasp that the government was hiding important truths about what was happening overhead. He was, in his mind, working to prevent another September 11 or Pearl Harbor–type calamity. He was doing it with the notion—far-fetched though it seemed in the moment—that someday Congress might revolutionize the government’s approach to UAPs, and a president might sign it into law.

If there was ever a stray doubt, it stemmed from a buddy—a longtime colleague with whom he’d served in Afghanistan and on the UAP issue, and whom Elizondo respected explicitly—who had tried to talk him out of this. “My advice to Lue was, ‘Don’t do this,’ knowing how difficult it would be,” says the retired career intelligence official who requested anonymity to avoid poking the nest of murder hornets that is the UAP community. He estimated Elizondo would have a 5 percent shot at pulling it off—“and later I revised that down to a 1 percent chance of success, because I knew what he was up against.”

Elizondo himself now had a pretty good idea.

UFOs have hovered at the fringes of America’s collective imagination for nearly eight decades. In the summer of 1947, a private pilot named Kenneth Arnold reported a formation of nine shiny objects flying past Mt. Rainier at two or three times the speed of sound. When this was widely published, it created a full-blown cultural phenomenon. The term “flying saucer” geysered from newspaper headlines into the public lexicon, and in the following six months, at least 850 similar observances were reported, according to one tally. About 50 percent of the nation believed in UFOs in the second half of the 20th century.

From the first reports, a scattering of scientists and military personnel sought to apply data and deeper research to the question, but the U.S. government waffled on how to respond. Members of a classified 1948 study, Project Sign, were divided on whether various reports indicated “interplanetary” phenomena or erroneous sightings—the celestial version of eye floaters. Thousands of sightings continued to pour in, and in 1952, Maj. Gen. John Samford, the Air Force director of intelligence, called a news conference to try to calm a rattled nation. Between 1,000 and 2,000 reports had been analyzed, he said, and in most cases, the military had determined they had nothing to do with aliens or spaceships. “However,” he allowed, a number of them “have been made by credible observers of relatively incredible things. It is this group of observations that we now are attempting to resolve.” From 1947 to 1969, the Air Force secretly filed such reports to Project Blue Book, a program set up to investigate and debunk UFOs. But Blue Book, and similar government and military programs in subsequent decades, made no headway on the question, at least publicly. And the lack of answers, or even acknowledgment, fueled widespread fascination and frustration.

As one of the leading mainstream journalists investigating the phenomenon over the past 20-plus years, Leslie Kean shares this enduring vexation. She began reporting on the issue in 2000, and in 2010 published the bestseller UFOs: Generals, Pilots, and Government Officials Go On the Record, widely considered a seminal book on the subject. For years, she advocated for the creation of a federal agency to openly address the topic. “We need government involvement here, because the civilian organizations are not equipped to deal with these phenomena,” she tells me. “And the government was just ignoring them—or making up stories about them.”

A key inflection point in the struggle for greater government transparency came in December 2017, when Kean and two other reporters published a piece in the New York Times about the existence of a secret Pentagon unit—the Advanced Aerospace Threat Identification Program (AATIP)—that had been working on the UAP issue under Lue Elizondo’s leadership. The sensational story came embedded with two videos recorded by military personnel, apparently showing aircraft flying without any visible means of propulsion and making maneuvers that seemed to defy physics. (A third video was later released.) Navy pilots expanded on these visuals with eyewitness accounts.

When the Times story on AATIP was published, Sean Cahill was riveted. In November 2004, he was a naval officer stationed aboard the USS Princeton off the coast of San Diego. He was standing watch on the bridge one night when the chief petty officer called to ask him to change navigation, letting slip that there was an anomaly they were looking into. Cahill made a joke about UFOs, but then, he says, “I just took the information, put my guys to work, steered the ship on certain courses, and ordered my lookouts to report anything they see.”

A couple of days later, Cahill, back on the bridge, received another call from the same officer. “He told me what he wanted me to do and where he wanted us to look, and he was really adamant about it. He was like, ‘Sean, I really need you to take this seriously.’”

He went outside and scanned the horizon with binoculars. Several thousand feet up “were five to seven lights—very bright white lights. No color, no blinking… And they were all moving in a circular pattern towards the center of this pattern,” he says. “Suddenly, one by one, when they reached the center of the circle, they disappeared.” It was as if they all passed through a funnel.

Cahill turned to a lookout nearby and said, “Did you fucking see that?” The lookout nodded.

The next day, in one of the most notorious incidents in UAP history, two crews in Navy FA-18F Super Hornets from the nearby USS Nimitz carrier investigated an object that had been detected on the Princeton’s radar and dropped 80,000 feet in an instant.

One of the people flying that day was Alex Dietrich, a strike fighter pilot from the VFA-41 “Black Aces” stationed on the Nimitz. Dietrich, who retired in 2021 as a lieutenant commander, earned a Bronze Star and an Air Medal in combat and had 1,250 hours of flight time. In November 2004, she was flying one of the two jets that were rerouted by air traffic controllers from their scheduled flight plan. “We argued with them, because we were supposed to go to a different working area that we had pre-briefed, but they said, ‘No, this is a real-world contact we need you to check out,’” she recalls. En route, a colleague speculated that a drug runner was headed up the coast in a Cessna. “That’s when somebody in the flight looked down and saw this disturbance in the water.” They observed a long, white oblong craft moving randomly at the water’s surface. The crews saw no exhaust coming from any visible source of propulsion. When Dietrich’s flight partner descended to take a closer look, the object rose toward his plane then abruptly disappeared. Later that day in a separate encounter, another flight crew recorded video on the so-called “Tic Tac” incident.

She wasn’t ordered to keep the event confidential, but she chose not to say anything publicly while on active duty. Four years passed after the incident before the Office of Naval Intelligence interviewed her about it. It wasn’t until 2021—when she had retired and the timing felt right—that she shared the story.

On a raw, drizzly night in Crystal City, Virginia, the exterior of the Kebob Palace is lit up like a neon fever dream, and the windows peer in on exuberant displays of Turkish art and vast quantities of tender meat on a stick. A thinly bearded man huddles cross-legged under a sliver of awning, spare-changing passersby. He looks vaguely alarmed when a man with an Abrams-tank physique suddenly looms over him.

“Hey, brother,” Lue Elizondo says. “How about a meal?” The man nods numbly, and Elizondo heads inside. It’s now February 2022, and more than four years have passed since he was a regular during his Pentagon days, but he knows the Kebob Palace will do a man right. He’s also aware that chicken biryani is not likely his new friend’s fix of choice. “But sometimes,” Elizondo says, “you have to give people what they need instead of what they want.”

He walks the extra plate back outside, then settles into a booth behind a hillock of rice, salad, bread, and seasoned chicken, seeming oblivious to the larger metaphor at hand. This question—of what people want versus what they need—has become a central mobilizing force of his life. Many Americans are happy to go about their lives, ignoring the possibility of UFOs. Elizondo says this is no longer a viable strategy.

While working for seven years on AATIP, he saw hard evidence that entities unknown to the Pentagon are using technology the United States cannot match or reproduce to have their way with the nation’s restricted airspace and sensitive nuclear sites. From a national security perspective, this was an existential threat. Yet the government has refused for decades to officially acknowledge it.

And so here he is. On TV, he’s a casting agent’s dream: an articulate, thoughtful, no-nonsense public speaker who happens to rock creative facial hair, a buzz cut, and a natty assortment of baseball caps and T-shirts. Pulling up photos on his phone from his time in Afghanistan, he jokes about his “sausage fingers,” leaving unmentioned his ferociously gnawed-off fingernails. One of the tattoos on his heavily inked oak-trunk arms reads Acceptum painetio—Latin for “accepted with regret.” It refers to his service during the war in Afghanistan. “There’s things that I’ve done in my life,” he says, by way of explanation, “that I wish I didn’t have to do.”

Elizondo approaches the emotionally charged UAP topic with a stubbornly phlegmatic disposition, addressing it in a way that’s forceful yet deliberate, calm, and measured. All of these traits seem to make him ideally suited to reach across America’s sociopolitical and geographical chasms. He’s flown to the nation’s capital from his home in Wyoming, where many of his neighbors are similarly desirous of personal space, or are a little paranoid, or both. He’s been up for 30 straight hours due to overlapping travel and work schedules, but over the next few days he’ll attend a series of meetings with individuals from the Department of Defense and Capitol Hill. Elizondo visits roughly once a month, disseminating data points, forging new alliances, and generally serving as a thread that weaves together the UAP narrative. His job, as he describes it, is to move between vastly disparate quadrants of government, informing the left hand that the right exists. “I’m just simply here,” he says, “to offer assistance in helping them understand the intricate nature of this topic.”

And the stakes, he says, are unmistakably high. “We know they”—unknown extraterrestrial beings—“are conducting some sort of ISR—intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance—on our military weapons systems and our nuclear technology, globally. That’s not up for debate, because we have declassified reporting to prove it.”

What remained to be seen was whether the government could be convinced to do something about it.

Elizondo was born into a family of Cuban activists. His father, Luis Sr., was 16 years old when he boarded the USS Houston to take part in the Bay of Pigs invasion. When the operation went sideways, he hid on a farm and swapped out his uniform for the farmer’s clothes, but Castro’s troops identified him by his boots. He was held for two years as a political prisoner in Cuba, more than a year of which he spent in the notorious Isle of Pines prison.

When he was released, he joined the rest of his family in exile in Miami. There he started a series of businesses, including a high-end restaurant in Sarasota. By the time Luis Jr. arrived, in 1972, the family lived comfortably but remained faithful to the cause. For the Elizondos, one of the era’s geopolitical saddle burrs took on stark real-life dimensions—strangers showing up at their home, his father hosting late-night meetings with the house surrounded by armed guards. There were death threats, and Elizondo remembers security sometimes picking him up at school in dark sedans. “I didn’t know it was politics; I just thought it was reality,” he says. “It was kind of weird growing up—most kids were playing G.I. Joe; we were kind of living it.” His parents had a troubled marriage—intense passion interspersed with china-shattering blowouts. “It was a very difficult relationship,” Elizondo says. Their divorce, when Lue was 10, carried catastrophic financial consequences. He lived with his mother, who was suddenly destitute; the bank foreclosed on their home and she had to hock her possessions to keep them housed. Lue recalls selling some of his clothes at a local flea market. He left a private school to attend far larger public schools, where he faced bullying.

“That’s when my life changed irrevocably,” he says. “I made a lot of dumb, dumb decisions as a kid…trying to get attention from anybody that would listen.”

His salvation was the ROTC. “I went in voluntarily, probably because I was pissed and probably because I was looking for a sense of purpose,” he says. “They were my parents and my mentors and my teachers when nobody else would be.”

He took out loans to attend the University of Miami, where he majored in microbiology and immunology as a pre-med, inspired by his grandfather, a well-known dentist in Havana. By then, he was a regular weightlifter and martial arts practitioner, and he worked as a bouncer, partly to take out his aggression on drunken miscreants. After graduating in 1995, he returned home to Jen one day—they were living together at the time—and said, “I have something to tell you.” He had joined the Army.

“I realized I didn’t want to look at test tubes for the rest of my life,” he says. “What I really wanted to do was serve—to get back to that feeling of being part of something bigger than yourself.”

After basic training, he eventually found his way into counterintelligence, with which he immediately connected. The work involves protecting the military from the opposition’s intelligence-gathering apparatus, and it might involve harvesting information and conducting activities to prevent spying, sabotage, or other disruptive actions. “It’s kind of like medicine,” he says. “You’re trying to figure out cause and effect on what makes a country do something, using the scientific method and deductive reasoning.”

Elizondo was deployed to Afghanistan not long after the war started in 2001. His assignment was to coordinate counterintelligence teams across the southern part of the country. His former colleague, the now-retired intelligence officer, says that in Kandahar, Elizondo was also de facto senior intelligence officer and “right-hand guy” for General James Mattis. During Mattis’s morning intelligence briefings, Elizondo often sat to his right. “Anytime there was anything questionable, Mattis would look at Lue for either confirmation or not,” the intelligence official says. (Mattis declined through a spokesman to comment, citing a “longstanding practice not to discuss questions related to intelligence matters or intelligence officers.”)

Elizondo “had a very direct and very broad knowledge of literally everything that was happening in the country, especially in southern Afghanistan,” the former intelligence official says. “Mattis trusted him implicitly, and Mattis is a brilliant guy. He’s not one who would put a stock in anyone who was fly-by-night.”

When the intelligence official returned to the U.S., he began working in an advisory capacity on AATIP. Run by the Department of Defense’s Defense Intelligence Agency, the program was created in 2007 at the behest of then Senate majority leader Harry Reid, who harbored a deep fascination with UFOs. In a 2009 letter requesting designation as a special access program, or SAP, which confers a high level of secrecy, he wrote that AATIP’s mission was to “assess far-term foreign advanced aerospace threats to the United States.”

The intelligence officer recommended Elizondo for a role, and a Pentagon official asked him for his opinion on UFOs. Elizondo said he’d never given them a thought. “I never had the luxury to do that,” he says. “I was too busy chasing bad guys.”

That was apparently what they were hoping to hear. He says he was “voluntold” to join AATIP in 2008, and by 2010, he was in charge. “He was basically a perfect fit,” the intelligence official says. “He had the CI background, but he also understood tech, especially how you protect and operate in support of what is colloquially referred to as black programs—classified technology programs.”

Elizondo had seen plenty in Afghanistan and elsewhere. But what he learned in the first months in AATIP shocked him.

The afternoon after the Kebob Palace meeting, I walk into the Lebanese Taverna in Pentagon City to find Elizondo and two men sitting in a semicircle at the back of a near-empty dining room. Flanking Elizondo are his lawyer, Daniel Sheehan, and a Pentagon employee who asks to remain anonymous. Sheehan is a legendary attorney with a storied history of clashing with the government; a Watergate burglar and the Black Panthers were among his clients. He is a burly man with an unruly tumble of curly gray hair who has spoken in public about alien encounters. Elizondo says he thinks of Sheehan as his flak jacket.

The three men agree that it’s a fraught time. The Pentagon employee looks grim-faced when the topic turns to internal tension over the UAP issue. Everyone orders lunch except for Elizondo, who only wants Turkish coffee, then grazes on the bread basket. Today he’s adopted an inner-Beltway look: blue dress shirt and suspenders, a navy suit jacket hanging on a nearby hook. His trademark baseball cap is gone, revealing a Brillo of dark hair. The conversation wends to the Pentagon’s default binary response to any threat: either extend a hand or point a weapon. The table’s consensus is that more options need to be available for potential intergalactic visitors.

With time to kill before the afternoon’s Capitol Hill meetings, he drives us around Pentagon City to the unremarkable buildings where he worked. There’s a walkway outside one of them, during his AATIP days, where he’d join a friend for a breather and they would shake their heads in disbelief at what they’d just seen, he says.

We next stop by the Pentagon’s 9/11 memorial, which happens to be temporarily closed. Standing at the fence, Elizondo recounts the hijacked airplane’s trajectory and collision with the building’s west side. He gazes at the scene for a long time, and an air of wistfulness passes over him. But when we head to the Capitol and he takes a call from a high-ranking member of the military about UAPs, he brightens.

Elizondo’s military indoctrination remains an inextricable element of his persona; his conversations are sprinkled with 10-4s and rogers. In rare windows of free time, he hunts deer—though he’s quick to point out that he uses the whole animal for sustenance. (“I’m not a trophy hunter,” he says. “I don’t like the act of killing.”) He restores old vehicles, especially military jeeps; one dates to the Korean War. “I have a bit of a workshop,” he says, “for when I just want to get away and play some rock and roll music and smoke a cigar while turning wrenches.”

Over near Capitol Hill, he ditches the car on a side street, 10 minutes away—a reminder of how much his life has changed since his corner-office days. His group heads into the Longworth Building for a session with Representative Tim Burchett, a Republican from Tennessee and lifelong devotee of the UAP issue. As a Christian, Burchett says, “I’ve always been curious about the unknown.”

Burchett also has long harbored a “genuine distrust of government”—going back to his boyhood, listening to his father’s stories about his World War II service in the Pacific and one mission in particular: “They told him it was going to be a mop-up kind of thing, and it was the bloodiest battle in the entire war,” he says.

This history sharpens his suspicions around UAPs. He believes the government has covered up important information about the phenomenon from Roswell through the present—and the only way to gain transparency is if regular Americans demand it. So when he flipped on the History Channel one evening and caught Unidentified, he was riveted.

Over the course of several meetings, Burchett has come to think of Elizondo as a friend and “kindred spirit”; Burchett, in turn, has become an agitator within Congress. “Dad-gum it, [people] need to talk to their own representatives and just say, ‘We need total disclosure—what we know about what this is. And stop with all the nonsense and release the videos—everything they’ve got.’”

Almost immediately after he joined AATIP in 2008, Elizondo says, he learned that UFOs were not the imaginary conjurings of the tinfoil-hat crowd. “I realized within a couple of meetings that there was something to this,” he says, “that this was real, and there were things coming into our controlled airspace affecting our military pilots, and we had no understanding of what it was.”

He and his team took a scientific, data-driven approach to the investigation, much like a counterintelligence officer would tackle it. “He didn’t jump to conclusions,” the intelligence official says. “He let the facts and evidence speak for themselves. And we came out of that with some very unexplained things and some inescapable conclusions—not the least of which is, we’re vulnerable.” This focus on science extends to Elizondo’s own UAP sighting. He doesn’t share details “because it is important that my personal observations do not get in the way of valid data collection and analysis—keep the data clean. We need to remove any type of confirmation bias. And that even includes myself.”

In 2016, Elizondo met Chris Mellon, who had been invited to an AATIP meeting by a mutual CIA acquaintance. Mellon had 20 years of experience in the intelligence field; he’d served as deputy assistant defense secretary for intelligence and advised members of Congress from both parties. The meeting’s topic was reports of regular intrusions in restricted airspace by unidentified aircraft. “These had been going on for two years at that point,” Mellon says, “and I was absolutely flabbergasted—horrified—to discover that nobody was doing anything about it, except for Lue.”

As Elizondo and Mellon began sharing connections and intelligence, they became increasingly alarmed. Over the past 76 years, the military has documented UAPs encounters with alarming frequency around U.S. nuclear assets. In one notorious instance in 1967, a UFO seemed to shut down nuclear-armed missiles at the Malmstrom Air Force Base in Montana.

AATIP was also documenting encounters at sensitive military installations, and with carrier strike groups training for deployment, in some cases as they crossed the Atlantic. “We’ve had military exercises canceled because there were unidentified aircraft on the training range, and they were afraid of midair collisions,” Mellon says. “These are aircraft that don’t have transponders, and haven’t filed flight plans, and nobody knows what they are.” The numbers of these encounters spiked in 2014 and 2015, to the point that former Navy pilot Ryan Graves said in a 2021 interview with 60 Minutes that sightings were a daily occurrence.

Just as shocking? No one at the Department of Defense (DoD) seemed interested. UAPs are a complex topic, and for all its elite war-making capabilities, the Pentagon is not an engine for processing nuance. The various branches and services are diffuse and siloed. Intelligence, no matter how useful, is generally hoarded.

In 2010 and 2011, Alex Dietrich served on the ground in Afghanistan as an engineer. She was struck by the degree to which the government operates on an information hamster wheel. “I kept being reminded that [the American military] hadn’t been there for 10 years—we had been there for one year 10 times… With each personnel upcycle there’s learning the projects, there’s figuring out the security situation, and there’s actually trying to get something done. And then it’s time to go home. Any program in the Pentagon has a similar turnover of leadership, and similar cycling.”

So it was with UAPs—only at the Pentagon, it wasn’t just bureaucratic churn; some people there didn’t want the information. Because of the little-green-men stigma, some bureaucratic substrata insulated their bosses from any involvement—including General Mattis, who by then had become Secretary of Defense, Mellon says. And several stymied AATIP efforts because the possibility of extraterrestrial life runs counter to their religious beliefs.

For others, by countenancing UAPs, the intelligence official says, “they have to admit that there actually is a legitimate, validated national security threat that they can’t do anything about.” Pentagon officials “always want to control the narrative, and if they can’t, their instinct is to kill it.”

Complicating things further, Elizondo felt compelled to exclude his boss, Garry Reid, from briefings, because he had a reputation for playing favorites and treating people poorly, including a case involving one of Elizondo’s reports. (In 2022, the DoD inspector general concluded an investigation determining that Reid, a now retired career military officer and career civil servant, had “created a widespread perception of an inappropriate relationship and favoritism” with a female subordinate.) Elizondo says his stance was: “‘I’m not going to tell you what I’m doing because I can’t trust you’… And that pissed a lot of people off.” (Reid did not respond when I reached out for comment.)

As political winds shifted, AATIP funding officially dried up in 2012, forcing Elizondo to bootstrap the program. “At that point,” he says, “we had to get very clever.” Because the program was never officially disbanded, he siphoned funds from other programs he was running.

“It was kind of his sheer force of will and personality that even kept it alive,” the intelligence official says. The problem was, the nation’s military leadership and elected officials didn’t grasp the urgency of the matter—and neither Elizondo nor anyone else in AATIP could do anything about that. At least, not while they were cloistered inside the Pentagon.

Running out of options to keep AATIP afloat as autumn 2017 arrived, Elizondo grew increasingly frustrated. He and his team knew that once they disbanded, the UAP issue would likely blink out. Gathered in their SCIF—Secure Compartmentalized Information Facility, a room where classified activities take place—Elizondo and his colleagues spitballed strategies. Elizondo could have leveraged his old relationship with Mattis and just walked into the Secretary’s office—but “he wasn’t going to do an end run and do it the wrong way,” the intelligence official says.

Mellon knew two direct reports to Mattis, and he too tried to work the chain of command. His impression was that aides surrounding the Secretary were worried that someone might use the issue to try to discredit him. “It finally became clear that nobody was going to do anything serious about this,” Mellon says. Elizondo couldn’t accept the idea of doing nothing. “I don’t think that we should keep this conversation quiet,” he says. “It hasn’t worked for [76] years. Let’s have a conversation.”

As he saw it, his only remaining play was to “take it to the streets.”

On October 4, 2017, Elizondo sent his resignation letter to Mattis. He cited “bureaucratic challenges and inflexible mindsets” that prevented Pentagon leadership from evaluating “unusual aerial systems interfering with military weapon platforms and displaying beyond next-generation capabilities.”

He and Mellon had plotted his next steps by analyzing where they and others had failed before and how they might avoid similar mistakes. They pieced together a five-point approach: legislative outreach; executive branch-level engagement; international engagement; media appearances; and public engagement (which included Unidentified and social media). Mellon focused on matchmaking pilots and other military personnel who had UAP experiences with members of Congress. Elizondo met with members of the Trump and Biden administrations to open a channel to send UAP information directly to the White House without the bureaucracy of the DoD or intelligence community.

The day after leaving his job, Elizondo talked with Leslie Kean. She recalls being stunned when she read Elizondo’s resignation letter. “It was historic that he was actually saying what he was saying to the Secretary of Defense,” she says. “It was a really big moment.”

Still, all of this shaped up as an extraordinarily difficult bank shot. Elizondo would try to accomplish what others had failed to do for nearly 80 years: convince the intractable and infinitely heterogenous United States government to finally, fully spill on the topic of UFOs.

His old ally in intelligence wished him well. “If anybody in the world can actually make this work, it’s you,” he told Elizondo. “But you’ve got to be prepared for what’s gonna come.”

Joseph Overton had an engineering degree, so when he took a job at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, he decided to apply his science background to answer a central question of American life: How do politicians decide which issues to support? To answer it, he built a model, and learned that elected officials zero in on policies that are accepted by society as valid—policies that fall within what’s now known as the Overton Window. Most officials avoid issues that lie outside that window, for fear that a fringe issue will be the career equivalent of stepping on the third rail.

What fits in the Overton Window fluctuates—not driven so much by prominent leaders or public figures, but by the complex and ever-shifting sands of community values and norms. Generally, policies come to be important based on societal consensus. For decades, the problem for those who cared about the UFO issue was that it fell outside the Overton Window. It was too out-there for people to take seriously. That was now Lue Elizondo’s challenge—and with his letter of resignation, it was also his burden. He soon realized no one was going to make it easy on him, either: The day after he submitted that letter, he received a call from his old boss, Garry Reid, who, as Elizondo later recounted in a formal complaint, “was clearly upset with me.”

Reid told Elizondo that if he continued on with what he was doing, he would “tell people you are crazy, and it might impact your security clearance,” according to Elizondo. In the month that followed, Elizondo received a number of calls from former colleagues warning him that Reid—furious for being excluded from AATIP briefings, among other reasons—was “coming after me” and insinuating that he was a fabricator.

In February 2018, Elizondo was told that his DoD computer had been confiscated in an attempt to determine whether he’d taken any unauthorized material when he left. That same month, he learned that the Air Force Office of Special Investigations had opened a probe into the release of the videos in the Times story, Elizondo says. The implication was that he had violated his security oath, but investigators found in 2019 that the videos were never classified. And in 2021, seemingly for good measure, he was again investigated and cleared.

Allies told Elizondo that Reid had even tried to revoke his access badge at the Pentagon, and security clearance. Though Elizondo was no longer working there, he was still meeting with DoD folks on the UAP issue. “I think they were literally watching his appearances, his social media, his press, his show, looking for any nugget they could use to go after him,” the intelligence official says. (Elizondo still retains his high-level security clearance.)

After the Times published its blockbuster, the story became global news. Many media outlets simply amplified the same report, but some were skeptical, questioning the existence of AATIP and Elizondo’s role in it—germinating seeds of doubt planted by ongoing hostility from some within the Pentagon. In 2019, for example, The Intercept quoted a Pentagon spokesman who said that Elizondo “had no responsibilities with regard to the AATIP program.” In 2020, a second spokesperson echoed these claims.

Some issues resolved quickly; Senator Harry Reid wrote an open letter affirming “as a matter of record Lue Elizondo’s involvement and leadership role in this program.” (The Senator died in 2021.) Elizondo tried to move on with his life. He relocated to California to be the head of security for To the Stars Academy of Arts & Science, the entertainment and research company created by Tom DeLonge, the former Blink-182 frontman and paranormal enthusiast. His presence there led to the starring role on Unidentified.

But by 2021, Elizondo was no longer playing defense. He retained attorney Daniel Sheehan and that year filed a 64-page complaint with the DoD Office of the Inspector General (OIG) alleging “malicious activities, coordinated disinformation, professional misconduct, whistleblower reprisal and explicit threats perpetrated by certain senior-level Pentagon officials.” A day later, the OIG announced an investigation “to determine the extent to which the DoD has taken actions” on UAPs. (Pentagon spokesperson Susan Gough referred questions about Elizondo’s allegations to the inspector general’s office. And Megan Reed of the OIG’s office said that as a matter of practice, the Inspector General “doesn’t provide status updates on Administrative Investigations.”)

Elizondo says that when challenged by people in the Pentagon, his mindset was: “I will go to the hilt. On speed dial right now, I can be in front of 40 million people in 10 minutes if I want to, and tell the people what I know. I don’t, because I’m trying to let the system work… I don’t want to break it; I want to fix it”—that is, cajole the government into holding itself accountable.

Meanwhile, he increasingly finds himself alternately embraced or vilified by various UFO subcultures—the conspiracists, the debunkers, the religious adherents, the profiteers, among others. Mick West runs an online forum called Metabunk, which is dedicated to unwinding conspiracies; over time, it has become focused on offering alternative explanations for purported UAP sightings. The soft-spoken Brit says that Elizondo is “a difficult person to read,” but he “thinks that aliens are real” and is trying to raise alarms about them. “That’s my charitable assessment of what he’s doing,” West says.

The uncharitable version? “He’s making stuff up for some nefarious reasons—like either he’s running a covert operation for the government, to cover up some kind of black operation, or it’s something else… but I always tend to go with the more charitable interpretation.”

Other critics feel aggrieved that Elizondo has elevated the issue—at the expense of government resources—without tangible, public proof that aircraft are capable of doing what various witnesses have described. Elizondo understands that frustration, to a point.

“Unfortunately this involves classified information,” he says, “but there absolutely is precedent for how these things move and it’s not just stories or eyewitnesses. There’s historical radar data, and some of those things are moving at 13,000 miles an hour in the 1950s. We have more than 70 years of data.”

On the three groundbreaking UAP videos, West argues that the “glowing aura” in one clip is “an artifact of the infrared camera.” In the other two, the pilots were working with recently upgraded radar and other systems. “So the most likely explanation, without knowing anything else,” he says, “is that they were not picking up mylar balloons before, with their old radar.”

West concedes that it’s a national security issue if military pilots encounter things that they can’t make sense of and are forced to abort missions. And Sean Cahill, the officer on the Princeton, says that West and his fellow skeptics might not realize that analytics crews on those ships immediately considered the same possibilities. After the 2004 sightings, he says, “They discussed everything the debunkers and everybody else thinks they haven’t figured out. These were highly educated tacticians. They talked about everything from temperature inversions to seagulls to these software glitches.” Nothing provided a plausible explanation. And none of the critics have access to classified Pentagon information that undoubtedly adds layers of detail and data.

By contrast, other factions of the UAP community are angry that Elizondo hasn’t released more data and videos—regardless of whether doing so violates his security clearance. For some devout ufologists, this perceived reticence has turned him into the skunk at the garden party. One Reddit thread titled “As time goes on, the more skeptical I get about Luis Elizondo” drew 697 comments such as “If Luis Elizondo stayed in his lane, I think he would feel way more trustworthy. But his appetite for speculating things that are unknowable is too big.” In another, a commenter described thinking that Elizondo was “the light leading us out of the darkness, now I’m convinced he’s a CIA plant.” Others assert that he is simply trying to cash in. Elizondo says the opposite is true: Leaving his job has created enormous financial stress for his family.

Elizondo concedes that the attacks have hurt. “It has been so tough on my family,” he says. (The Elizondos have two daughters; one is nearly finished with a bachelor’s degree and the other is in graduate school.) “It’s terrible. It’s been so bad, this whole journey… My wife is always asking me, ‘Why are you doing this? These people who don’t give a shit, who don’t appreciate your sacrifice?’ And I try to tell her all the time, ‘Look, I’m doing it for our kids. I’m doing it because it’s the right thing to do.’”

Especially after the attacks on Paul Pelosi and Salman Rushdie, he’s wary. “I’m way more worried about [UAP-related death threats] than I ever was about Al Qaeda or ISIS,” he says. Since 2021, he has stockpiled a small personal armory at home, and acquired two more German shepherds.

Despite these challenges, something remarkable has happened: The UAP issue has gradually moved inside the Overton Window. In May 2022, a House Intelligence subcommittee held its first public hearing on UFOs since the 1960s. Rep. Tim Burchett is not a committee member, because he won’t keep the government’s secrets on the topic, he says. He attended nonetheless, but left frustrated after being denied the chance to ask a question.

But what may not have been apparent in the moment was the extent to which the hearing amplified the conversation, lending the issue its own gravitational reality. Since then, senators who have taken up the UAP mantle include a presidential candidate from each party: Democrat Kirsten Gillibrand and Republican Marco Rubio. (Both declined to comment, through spokespeople.) Prominent past and present public figures in government have acknowledged the issue, including NASA administrator Bill Nelson; director of national intelligence Avril Haines and her predecessor, John Ratcliffe; former CIA director James Woolsey; even former Presidents Obama and Clinton. “Reporters are finally coming out saying, ‘Hey, that guy just said that—we need to report it, whether we think it’s kooky or not,’” Elizondo says.

The military’s long-term UAP freeze-out is also showing signs of thawing. In April 2019, the Navy revised its official guidelines for pilots and other personnel, encouraging them to report UAPs without fear of internal blowback.

Beginning in 2020, AATIP was reconstituted several times, under different names, and Elizondo served as an advisor and aide-de-camp with each, helping advance their work. In July 2022, the Pentagon announced its latest iteration: the All-Domain Anomaly Resolution Office. Significantly, AARO’s mission is to synchronize efforts across the DoD and with other departments, which in theory will end the siloing of information. And in October, NASA announced the creation of an independent study team focused on UAPs, comprised of scholars, scientists, a former astronaut, and a Federal Aviation Administration official, among others.

Elizondo’s efforts with the executive branch helped lead the Biden administration to create an interagency team to study the broader policy implications for the detection and analysis of UAPs—an initiative announced on February 13, days after the U.S. shot down several aerial objects over its airspace.

Amidst much of this, Elizondo pulled back from public view, extracting himself from social-media squabbles. He departed To the Stars in 2019 and wrapped Unidentified after two seasons, then left California for the wilds of Wyoming. Elizondo and his book editor are finalizing his manuscript, which he says will be “a very eye-opening read.” He is considering a future run for Congress. He believes the nation is ready for full disclosure on the UAP situation.

Elizondo’s crowning achievement to date came on December 23, 2022. That day President Biden signed the National Defense Authorization Act, which includes numerous far-reaching UAP provisions. One requires the government to own up to whether it’s been concealing physical evidence of alien spacecraft. “That was stunning,” Mellon says. “There was bipartisan support, and the reason is because they received credible sourcing and credible testimony indicating that that may, in fact, be the case.”

The law also requires the Pentagon to create a secure mechanism for government and defense employees to report UAP sightings. AARO will now provide regular reports, analyses, and briefings on UAP activity to Congress, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence must provide an unclassified version. It must also develop an in-depth “science plan” to explain UAPs that “exceed the known state of the art in science and technology,” and deploy field investigations of incidents. Intelligence services from each military branch must send a liaison officer to AARO, and the agency head will report directly to top DoD and intelligence brass to avoid bureaucratic obfuscation.

There’s more: For the first time, the U.S. will use the intelligence community’s multibillion-dollar technical apparatuses, which include spy satellites, weather balloons, and the most powerful radars in the world, to track UAP activity in real time. “There’s nothing that compares to the assets the U.S. intelligence community has. That power is now being harnessed to help answer [UAP] questions,” says Mellon.

And whistleblower protection—informed by Elizondo’s experiences—will help ensure that no one fears retribution for calling out any failures to implement these new policies.

Meanwhile, the former intelligence official says that an army of more than 1,500 volunteers within the intelligence community now meets on classified networks where they analyze UAP videos and data. This group includes “literally everyone—CIA to the [National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency] and everyone in between.”

The legislation figures to end the Pentagon’s gnomish, decades-long silence. Leslie Kean, the longtime UAP journalist, sees a “radical change,” all of it stemming from Elizondo’s decision to go public. “Everything that’s happened since then really stemmed from his resignation,” she says. “It’s like a snowballing effect… It gave permission, in a sense, for Congress to do this without having to worry about the stigma anymore.”

Through all of this, sightings and reports continue to flow in. “They’re happening all the time,” Elizondo says. This January, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence reported that 366 new UAP incidents had been reported to U.S. intelligence agencies since March 2021.

The numbers are such that Sean Cahill, for one, is frightened that humans are “about to get steamrolled by something.” But, he says, “I have really high hopes because we’re having the discussion in the public eye.” Maybe the amplified UAP conversation will prove to be pivotal for humanity, or maybe Mick West will be right, and all of the phenomena will finally be explained away. Maybe the military and NASA will uncover what Leslie Kean calls the ultimate goal: providing “some level of proof…that establishes the reality of this being a nonhuman, non-manmade technology or phenomenon.” Either way, Elizondo and his allies made it safe for the public to have a conversation about it, and for the government to have a conversation with itself. The window is now open.

Elizondo is not yet ready for a victory lap. His life is still frayed and diffuse. For income, he’s now employed by a Washington-based software company that does work with the federal government. There is still information to be disseminated, research to be done, science to be conducted. And of course, there is still the question of what is up there, in the skies, causing so much tumult down below. “I’d love to say ‘mission complete,’” he says, “but we’re not there yet. There’s still more work to be done.”

And yet. The day Biden signed the historic defense bill, Elizondo walked out onto his front porch and allowed himself a quiet 10 minutes. His mind drifted back across the past five years: the meetings, the phone calls, the character attacks, the tweets, the travel, the arguments with both allies and detractors, the TV shoots and re-shoots, the requests to take his picture at random restaurants, the hefting of black-water tanks, the efforts to soothe his wife’s frustration with the unforeseen radical detour that their lives had taken—all that went into the single-handed and collective pushing of the boulder up the hill, over and over, every day, until finally, finally, it stopped rolling back down.

As he stood there, all of those years of work, and all that might still happen, felt at least for a short time as far off as the Wyoming horizon. He inhaled the mountain air and gazed into the immense sky. The calendar had just flipped past the winter solstice, and the days were crisp and abrupt. In a blink, the sky would be full of stars.

David Howard has written for many national publications and is the author of two nonfiction books, most recently Chasing Phil: The Adventures of Two Undercover Agents with the World’s Most Charming Con Man.

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from Popular Mechanics can be found here.