The Smiley Face Killers Conspiracy Theory Died Down. Then Came TikTok

Don’t take rides from strangers. It’s a simple edict ingrained into kids from a young age. But after a TikTok user posted a video about being offered a late-night ride outside a Chicago bar, an eager comments section and TikTok’s sleuthing machine set off a chain reaction — one that resurfaced one of the longest-running serial killer conspiracy theories in the country.

On March 9, TikToker Ken Waks posted a video encouraging his followers to avoid what he called a “terrifying” encounter. “This has happened to me 2x in the last 6 weeks,” he wrote in the caption, describing how he was offered a ride home by a strange car that then sped off. “People have been going missing all [year] after leaving a bar or party at night and are never heard from again.” But instead of chalking the experience up to a strange encounter, Waks’ mind went in a much more sinister direction — this was the work of a serial killer.

After people filled his comments section with their own stories of being approached late at night, Waks began posting that the unsolicited car rides were the missing link that connected a string of fatal drownings in the Chicago River to a serial killer. Though the Chicago Police Department ruled all the deaths accidental, each of the people found in the river were last seen leaving Chicago bars. Blaming unexplained deaths on serial killers is a common move on social media, but Waks used his experience (and overflowing comments section) to theorize that the alleged killers were getting their victims while offering them rides late at night and then drugging them. “I know how they’re going missing. I know how they’re all connected,” he said in a TikTok, confidently describing how easy it would be for young, strong men to be overpowered by strangers while they were drunk. “I know why the cops and the media are not doing anything or covering it. And I know what we can do about it.”

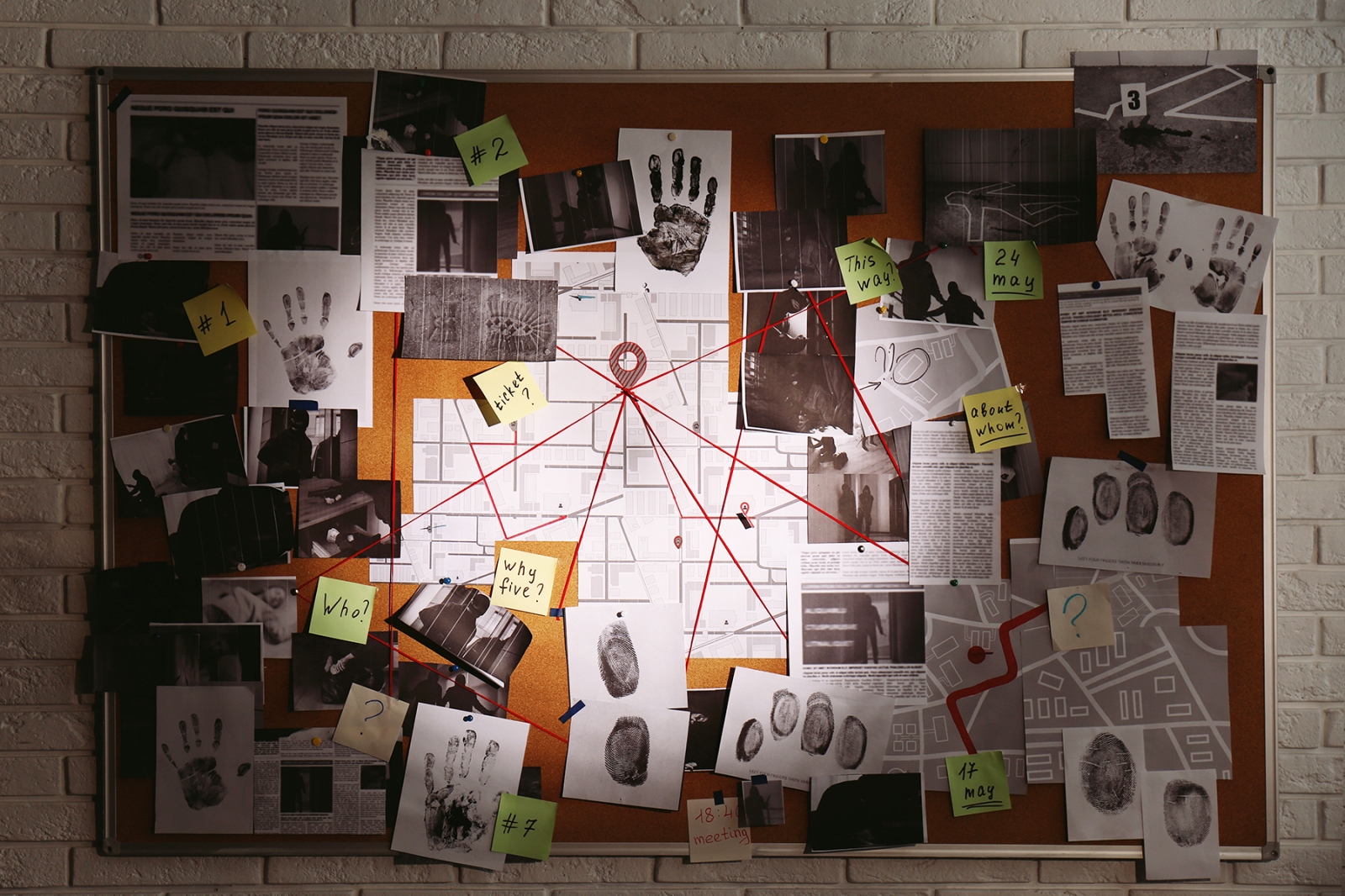

Over the course of seven weeks, Waks shared his findings on TikTok, posting homemade maps charting each death, and expanding his research to major cities across the country. “This is bigger than just Chicago or Austin,’ Waks wrote. “Nationwide, men are going missing under the same circumstances and found days or weeks later.” The creator went from posting the occasional video to actually visiting the police station IRL with what he thought was vital information. When they didn’t listen, he turned to his ever-growing TikTok followers. “If the police and the news aren’t going to do anything to increase public safety about this and raise awareness, I’m going to do it myself.”

It’s a trope in countless shows and movies about serial killers. Before the handcuffs, before the convictions, there’s usually a person trying desperately to be believed. That’s probably why Wak’s videos, which had previously focused on startup culture, started drawing millions of views and thousands of comments. But there’s another reason why Waks’ theory got so much traction: people have believed it before.

In 1997, Fordham College student Patrick McNeill left a Manhattan bar after a night out to head back to campus. It was the last time the 21-year-old was seen alive. After a month of intense searching, police discovered McNeill’s body floating in the East River near the 65th Street Pier. According to the autopsy report, there were no signs of foul play and McNeill’s death was ruled an accidental drowning under the belief the student had simply been too drunk and fallen into the water. New York Police Department Detective Kevin Gannon, one of the investigators on the case, disagreed. And for the past 20 years, Gannon, who’s now retired, has dedicated his life to proving that McNeill’s death — and the drownings of hundreds of men across the country — are not accidental, as authorities have ruled, but the work of a ganglike group of clandestine killers.

Alongside former New York Police Department detective Anthony Duarte and criminal justice professor Lee Gilbertson, Gannon is one of the loudest proponents of the Smiley Face Killers Theory. The theory hinges on the idea that smiley face graffiti found near the scenes of the crimes link hundreds of accidental drownings in the U.S together. It’s been continually derided, first by the FBI in a 2008 statement, then by dozens of crime experts, and a detailed paper by Minneapolis’ Center for Homicide Research. But that hasn’t kept Gannon and his colleagues from continuing their work, including publishing a book in 2014, and a recent six-part Oxygen series Smiley Face Killers: The Hunt for Justice.

Gannon did not reply to an interview request or requests for comment. But in a 2019 interview, he told Rolling Stone he was determined to prove his theory and get justice for the alleged victims. “When we put out who’s doing this and why, I don’t think [the FBI] will have any option but to get involved,” he said. “We have to do something to bring the individuals responsible for this to justice. And I’m telling you, we won’t stop until we do.” And he appears to have kept that promise. On April 26, Waks shared a TikTok video saying he and Gannon were now “teammates” and working together to use his data. “My team has officially joined his as they open their investigation into the Smiley Face Gang,” wrote in the caption. “With all of [us] working together (our teams and everyone who sends me information) we will finally be able to bring these people to justice and get answers for those families. Welcome to the team y’all, let’s get to work.”

There’s nothing new about people’s interest in true crime — and social media has put it in front of people’s eyes in real-time. (Think the disappearance of Gabby Petito or the Idaho Murders.) But while advocates for the medium say online interest helps solve cases, the overwhelming thirst for serial killer content can cause its own harm. According to Cal State Fullerton professor Adam Golub, the speed at which citizen journalism — and sometimes misinformation — spreads on TikTok means that it’s more than likely that the app will become a launching pad for reviving other old or previously debunked true crime theories.

“When we have this new fear and fascination with some kind of serial killer case, it makes sense that Tik Tok is going to become the place where everyday people propose their theories,” Golub says. “I think that’s inherently problematic, but this has been a really mixed bag when it comes to citizen journalism and armchair investigators. On one hand, people are contributing to reopening cold cases and potentially exonerating people who have been accused of crimes. But there’s such little ethical supervision and regulation that it opens the door to speculation, generating false hopes, and exploitation through monetization.”

It was a perceived monetization that turned Waks from a potential hero to TikTok controversy. In at least two videos promoting his investigations, Waks mentioned Foresyte, a calendar app startup where he worked as Chief Marketing Officer. And in a now-deleted Linkedin post, Foresyte’s CEO Stephen Eddy celebrated an increase in downloads that he linked to Waks’ viral attention. Soon after, though, hundreds of followers accused Waks of pursuing the investigation and virality to give his app more buzz. “He is profiting off of people’s tragedies,” user Meredith Lynch said. “This type of content is dangerous,” added creator Justin Burnett.

When initially reached for comment, Foresyte told Rolling Stone that Waks’ mention of the app was “misguided” and not part of a marketing strategy. Following continued backlash, Forsyte announced Waks had “parted ways” with the company. “While Ken brought energy and ambition to our team as CMO, the unrelated developments that have unfolded in his private life… require both parties to move forward in other directions,” a spokesperson for Foresyte says. Waks declined requests for additional comment, but posted on TikTok that he wished them “all the best as we move forward separately.”

In one of two apology videos posted on TikTok, Waks said mentioning the app alongside his research was “insensitive” but called it an honest mistake. “I frankly got a little bit lost in the sauce over the story,” he said. Waks announced he wouldn’t stop the research, but he would cease to publish his findings on TikTok.

Waks declined to be interviewed by Rolling Stone, but he said over email that his plan is to hand over his findings to the proper authorities “who can commit the time required to pursue these cases alongside the detectives with whom I was in contact.” And he says that his videos created a sense of connection for those who saw them. “So many others have either experienced similar incidents to my own — cars approaching them late at night with unsettling interactions — or have been closely connected with the missing persons of interest,” Waks says. “Several people came forward with information relevant to the cases and it created a real sense of community.”

But Golub adds that as true crime becomes more centered on content and keeping people entertained, it’s often at the expense of victims and their memories.

“The serial killer has become a stock character in popular culture, and in that sense, we feel like we know how to solve the case because we’ve seen it solved so many times. But TikTok is operating as this ethical wasteland. There seems to be no regulation or consequences for this stuff,” Golub says. “True crime neglects the victims and talks about the perpetrator. And in this weird way now, the creator and his attempt to create this narrative, has become the center of the story, instead of the victims.”