Can the Great Reset really create a gentler, more equitable capitalism? | CBC Radio

Ideas53:59The Great Reset

*Originally published on May 24, 2023.

When Marc Benioff, the co-founder and CEO of the software giant Salesforce, arrived at the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in January 2020, he didn’t look like the other billionaires gathered there.

Instead of a cashmere sweater vest under a smartly tailored blazer, Benioff was wearing a dark suit and a black tie.

Asked to explain his wardrobe choice, Benioff replied, “I’m at a funeral for capitalism here in Davos.”

But Davos is probably the last place you’d expect to see capitalism laid to rest.

Some of the most successful capitalists in the world attend the annual get-together, and Benioff is among them.

The software company he co-founded in 1999 is currently valued at about $190 billion US, and his net worth is estimated at about $7 billion.

He’s also part of a growing number of the super rich who say the system that worked so well for them has led to environmental destruction, income inequality and social dysfunction.

That system has outlived its usefulness, according to Benioff, and needs to be replaced by a “new kind of capitalism that’s not just about making money.”

From shareholders to stakeholders

This new kind of capitalism is known as “stakeholder capitalism.”

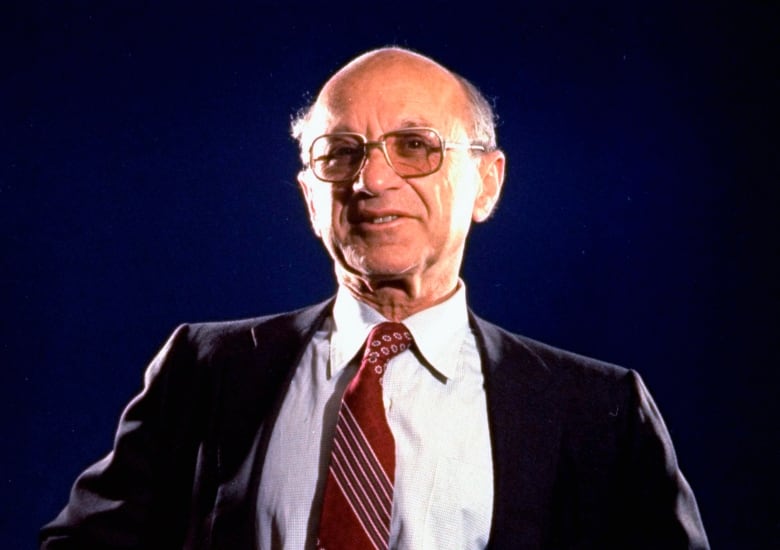

Klaus Schwab, the founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum (WEF), coined that term in response to a September 1970 essay in the New York Times by Nobel Prize-winning American economist Milton Friedman.

Friedman attacked business leaders who talked about their companies having a “social responsibility” to deal with issues like poverty and the environment.

Instead, Friedman extolled the virtues of “shareholder capitalism,” where the primary responsibility of corporations was to their shareholders. People running corporations weren’t there to solve society’s problems, but to increase profits, resulting in greater prosperity for all.

Schwab countered that CEOs shouldn’t ignore shareholder needs for a healthy return on investments, but should also consider the needs of other “stakeholders,” including workers, suppliers, customers, civil society and communities.

They all had to work together to solve world problems.

“Multi-stakeholder partnerships,” he argued, would be the way of the future.

Stakeholder capitalism was a compelling idea, and many CEOs were happy to pay lip service to it, but they were ultimately rewarded for maximizing shareholder returns, not saving the world.

Turning point

For most of the past 50 years, Friedman’s ideas dominated corporate boardrooms. But there are signs the tide has started to turn.

After years of stagnant wage growth, job losses, low social mobility, a growing climate crisis, rising income inequality and political threats from the anti-globalization policies of Donald Trump on the right to the socialist democratic ideals of Bernie Sanders on the left, CEOs like Benioff have concluded it’s time for a re-think.

“If your orientation is just about making money,” he told a Davos audience in 2019, “I don’t think you’re going to hang out very long as a CEO or a founder of a company.”

That same year, the U.S. Business Roundtable, made up of the country’s top CEOs, issued a statement about the purpose of the corporation. After 50 years of insisting corporations existed to serve shareholders, they now fully embraced a capitalism that served stakeholders.

In June 2020, the WEF launched its Great Reset initiative, proclaiming “now is the time to set the reset button on capitalism.”

They warned of an urgent need for global stakeholders to co-operate in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis. The WEF said the Great Reset would be a rare opportunity to build entirely new foundations for economic and social systems while addressing global challenges like income inequality and climate change.

But critics say their version of stakeholder capitalism could just as easily be used to entrench the power of the corporate elite and influence and undermine democracy.

In 2021, many of Canada’s most powerful business and industry associations joined former federal cabinet ministers Lisa Raitt and Anne McLellan to form The Coalition for a Better Future to promote stakeholder capitalism.

“Capitalism as we’ve known it isn’t going to work any longer,” McLellan declared.

Beyond the bottom line

One of Canada’s biggest proponents of reinventing capitalism is Guy Cormier, chairman and CEO of the Montreal-based financial services co-operative Desjardins Group, which manages over $91 billion in assets.

“We have built capitalism in a way where we use resources with a mindset where they will always be available and there is no price for these resources,” Cormier argued in a recent interview. “But now we know that with too much consumption, too much capitalism, there is more inequality and more pollution.

“We’ve seen some people who are losing faith in institutions, in democracy, so when you put that all together, maybe there’s something that we must change in capitalism.”

Benioff believes corporations can think beyond the bottom line.

He likes to boast about the hundreds of millions of dollars Salesforce gives to support public schools, to cut carbon emissions, to feed the hungry and to house the homeless.

He refers to his employees as his “ohana,” the Hawaiian word for family, all while providing impressive shareholder returns.

But in 2022, those returns became less impressive. Salesforce was still making healthy profits, but costs were up, revenues were down and the stock dropped nearly 50 per cent. Activist investors started buying up shares, looking to make changes in the company. Some complained it was too “woke.”

Benioff responded by firing 10 per cent of his “ohana,” cutting costs and buying back billions of dollars of Salesforce shares. The plan worked. The stock climbed about 40 per cent in the first quarter of 2023.

Cleary, these were not the actions of a man who thought shareholder capitalism was dead. The market spoke, he answered. Despite all the lofty talk of focusing on the needs of stakeholders, business was still about making money.

Still, Cormier of Desjardins Group, believes change is possible.

He says younger investors want financial returns, but they’re also concerned about the impact of their returns on the environment.

“I feel in the next five, 10 years, returns will be important, but not necessarily the No. 1 factor.”

Who chooses the stakeholders?

Even if that turns out to be true, there are other important questions about stakeholder capitalism — like who chooses the stakeholders, and how much power will they have?

Businesses will want a seat at the table, but the corporate elite that flock to Davos every year represent only a small part of the business community. Will other voices be heard?

Workers are important stakeholders, but not, apparently, if they belong to a union. Many corporations, including Starbucks, Amazon, Apple and Alphabet, Google’s parent company, are waging fierce campaigns to prevent them from unionizing.

Then there are all the civil society groups — including relevant NGOs, community organizations and charities — who may have legitimate claims as stakeholders, but who don’t necessarily agree on solutions to big problems like the climate emergency.

Who chooses whose voices are heard? In a democracy, the obvious answer is that elected representatives should be at the head of the table choosing who else will be there.

But that’s not how Benioff and other CEOs at Davos see things.

“We have to take action,” Benioff told a virtual meeting of the WEF in 2021.

“And we can’t just say that government is going to take action, because we know that government is mostly not very effective today.”

For Benioff, the pandemic proved that governments simply weren’t capable of solving global problems. Only business could do that.

“It was CEOs in many, many cases all over the world who were the heroes,” he said. “They are the ones who stepped forward with their financial resources, their corporate resources, their employees, their factories, and pivoted rapidly — not for profit, but to save the world.”

Global corporate elites like Benioff are convinced that corporations are currently the only fully functional organizations in society, and believe they have to take the lead in any kind of partnership with government and other stakeholders.

Potential harms

Steven Globerman, a senior fellow with the Fraser Institute, finds that a very disturbing prospect.

“If you’re going to concede that, you’re basically saying democracy doesn’t work,” he said in a recent interview. “We might as well just have a bunch of autocrats deciding what’s socially important and what’s not.”

Globerman is a free market economist. The idea of limiting government involvement in decision making would normally appeal to him, but when it comes to the version of stakeholder capitalism being advanced by the WEF, he thinks we should be very wary about billionaires bearing gifts.

There’s an important distinction to be made between limited government and no government at all, he says.

“There’s the potential for a lot of harm being done if government essentially is a partner with business, where the business leaders in a sense, get to set the social agenda.”

*This episode was produced by Ira Basen.