Despite Stigma, UFO Survey Finds 19% of Academics Say They’ve Had Strange Sightings

Last week, an independent NASA panel reported that the lack of quality data on the phenomena, as well as negative public opinions about whether the research should be pursued, are the two biggest barriers to knowing more.

Bethany A. Bell, an associate professor in School of Education and Human Development at the University of Virginia, is one of the academics who is open to asking questions.

Bell joined primary authors Marissa E. Yingling and Charlton W. Yingling of the University of Louisville on their quest to know what scholars might be thinking about UFOs, but not willing to say out loud.

“My decision to join the team was mainly curiosity and interest in helping move a historically ‘taboo’ topic into intellectual spaces,” said Bell, who chairs the Department of Education Leadership, Foundations and Policy.

In light of the NASA report, which now uses the government-preferred term “unidentified anomalous phenomena,” the professors’ May 23 publication of findings in the journal Humanities and Social Science Communications couldn’t have been timelier.

The Survey and the Stigma

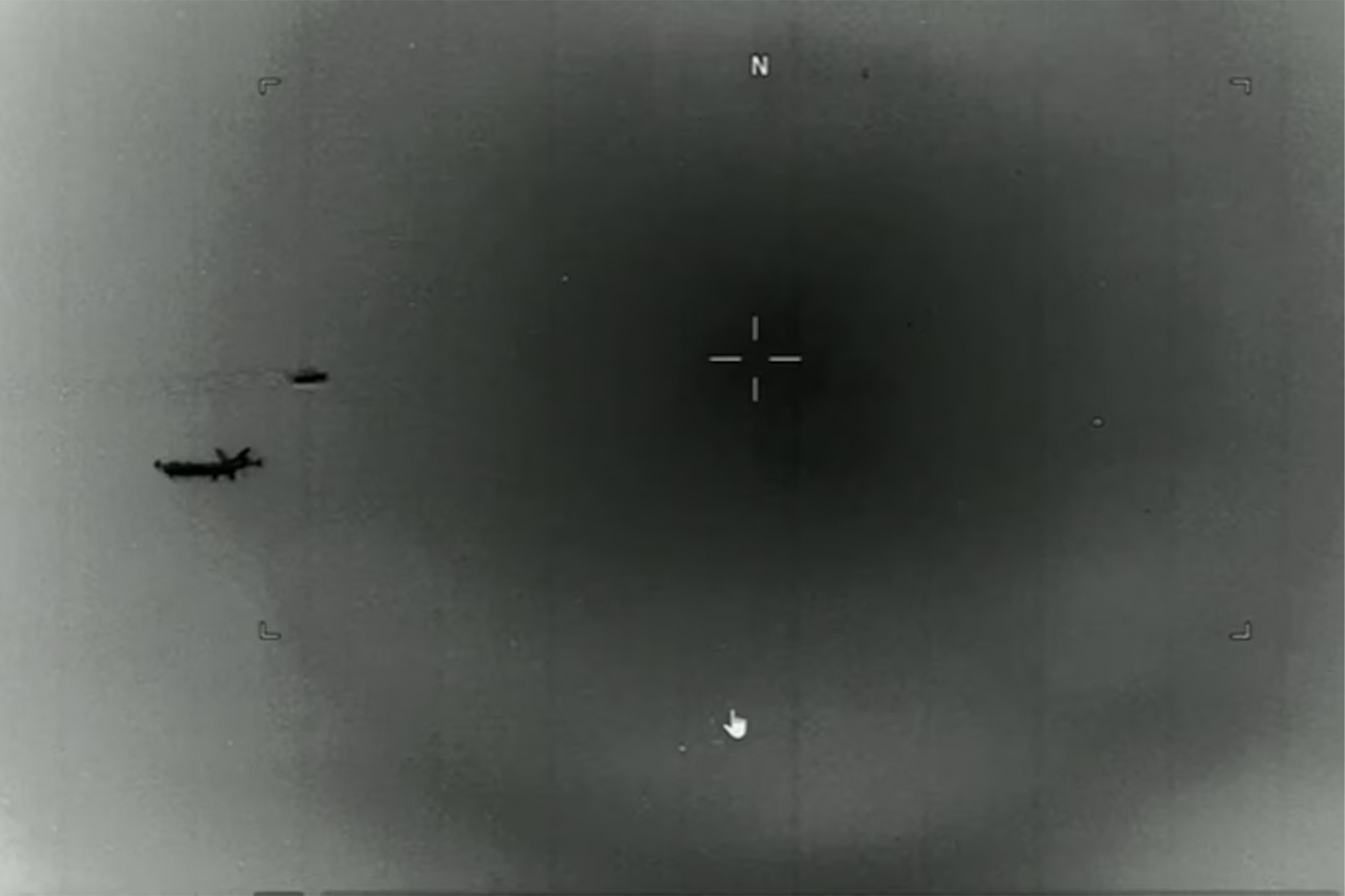

Hard to document, much less replicate for further study, the mysterious sightings often occur quickly, remotely and at night.

Those who choose to report an encounter do so at their own risk. Society has long been trained to respond with skepticism, if not outright hostility. Given the stigma, serious-minded people such as academics have learned to keep unexplainable encounters to themselves.

“Universities are institutions within the larger society – they are influenced by societal and cultural norms,” Bell said. “It seems that historically, when the topic of UFOs began to appear, UFOs became synonymous with extraterrestrial beings – something that the majority of people consider in the same realm as Bigfoot or ‘ghosts’ and other paranormal phenomena.”

But ever since the government added its imprimatur to investigate with last year’s congressional hearings, the first on the topic in 50 years, the three university professors wanted to take the temperature of their fellow academics.

The team sent their survey to tenured and tenure-track faculty in 14 disciplines at 144 U.S. doctoral universities classified as conducting “very high research activity” by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education.

In addition to the types of academics one might expect, such as astronomers and physicists, the researchers wanted to hear from faculty in the social sciences, humanities and arts.

The team asked the academics how curious they were about the topic, how aware were they of related news developments and how interested they might be in conducting research, among other questions.

Even though the survey allowed for anonymity, the response rate was relatively small. Of the nearly 40,000 academics who received the email, only 1,549 returned answers.

Many of the professors apparently thought the survey was spam. After all, who asks about such things?

Some reacted unkindly. One wrote, “Tenure might be tricky for you – good luck.”

Surprising Findings and Next Steps

In all of the instances in which the survey asked about awareness of news developments, most people said they were “not at all aware” – perhaps pointing to the taboo of discussion and sharing of the subject matter within their circles.

Curiosity was the biggest driver for those who said they had kept up with the news.