Tarnished Brand

There is a strange dramatic irony that comes with rewatching Russell Brand’s infamous Newsnight interview from October 2013. The dynamics—Brand’s brashness, Jeremy Paxman’s dismissiveness, the ideas being batted around—almost trigger a wince. Despite being roundly mocked for his views, and for admitting he did not vote, Brand’s critiques of power—who really has it and how you get it—ring sharply true to modern politics. At the time, his thinking was treated as outrageous, or at least fringe; now it is a regular feature of mainstream debate.

“I’m just asking you why we should take you seriously when you’re so unspecific,” Paxman says at one point. Brand replies: “I don’t mind if you take me seriously. I’m here just to draw attention to a few ideas—I just want to have a little bit of a laugh.”

This ethos appeared central to Brand’s streak of political success and almost inescapable presence from the early 2010s until the end of the 2015 general election (he was notably absent from the political chaos of 2016). Throughout, his focus was on changing people’s minds about ideas and policies—from representative democracy to climate change mitigation and addiction treatments—rather than their views on parties or politicians. During this period, he became as much an icon as a punching bag, his name synonymous with an idealist style of left-wing thinking and a set of beliefs that have since only grown in popularity-—all the while maintaining his global comedy fame.

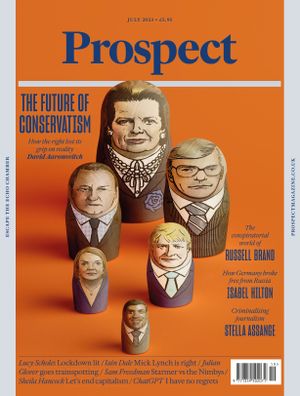

Since then, Brand has largely disappeared into the ether for most people, occasionally resurfacing to take on minor roles in blockbuster films and other smaller projects. He lives, on the surface, a quiet, conventional life with his wife and two kids in rural Oxfordshire. However, for the more than 13m subscribers to his accounts on TikTok, Instagram, YouTube and the right-wing streaming site Rumble, Brand is not only thriving, but more relevant than ever. Now he is using his anti–establishment views and comedic charm—once based on broadly left-wing principles—to broadcast (and sometimes even promote) misinformation and conspiracy theories on topics ranging from 9/11 to vaccines and the involvement (or not) of the FBI and CIA in selecting US presidents.

Today, the Russell Brand empire is monumentally wide-reaching: he runs annual wellness retreats promoting alternative medicine, streams daily from his shed near Henley, posts conspiracy-minded TikTok videos; he’s even done an anti-woke comedy tour and appeared on TV panels sympathetic to conspiracy theories. He, of course, also podcasts. All of this has inspired a cult-like new following.

It would be easy to write Brand off as a small part of a booming cottage industry of alt-right, online talking heads. After all, there are plenty of men ranting on the internet, from the comfort of their homes, regurgitating popular conspiracy theories for cheap views and gaining a following. (Despite his professed interest and openness to debate, multiple Brand representatives did not accept an interview request for this piece.) But what Brand is doing is unusual in terms of its style, tactics, content and in how effective it is in getting people to believe him. It may, in its potentially extraordinary impacts, even be unique.

It can be difficult to determine with complete certainty just how influential any individual is, but we can get a good sense by looking at their reach—how many people are seeing and listening to them, and how often and at what rate. Few will ever manage anything close to the audience Brand currently boasts.

For many years his main outlet was YouTube, where he has been posting for more than a decade and has more than six million subscribers. This is where most of his fans seem to congregate. Once an irregular catalogue of clips from media appearances, for the last two years his account has featured near-daily videos. He typically covers topical news stories from a sceptical or misinformation-driven angle—whether the theme is Covid-19, free speech or the war in Ukraine (Brand is a vociferous critic of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky). Some of the most popular videos he’s posted surround these subjects and have drawn in millions of views (one recent video, promoting the popular “Great Reset” conspiracy theory, received 1.5m; another, suggesting a global Covid-19 “cover-up” from 2021, has received 5.1m).

These numbers are not wholly uncommon on YouTube: PewDiePie or MrBeast, some of the most subscribed-to YouTubers, get several million views on each of their videos. Ben Shapiro, another right-wing YouTube commentator, has roughly the same viewership on the platform. But Brand’s real influence lies in the public’s strong appetite to hear him discuss and occasionally share misinformation, streaming every day to audiences that have now grown to near half a million.

In September, it was announced that Brand would begin exclusively livestreaming each weekday on Rumble, an online video platform that’s similar to YouTube but caters to audiences that are eager for critiques of mainstream views, many of whom are seeking content that’s explicitly alt-right and anti-censorship. (Brand cited YouTube’s censorship of his videos in his reasoning for pivoting.)

Rumble gained a reputation as a platform where false claims are spread at the start of the pandemic. It received investment from venture capitalist Peter Thiel—co-founder of PayPal and Palantir, and the first outside investor in Facebook, who has put millions of dollars behind Trump-aligned Republicans—in the same month a report carried out by Wired found that the site sends viewers “tumbling towards misinformation”. But the platform is growing rapidly—it has reported that its monthly active user base rose to 80m in the final quarter of 2022, more than double that of the previous year.

Brand can be subtle in the way he approaches certain subjects, shrouding conspiracy theories in a veil of accepted truths

Roughly 300,000 viewers tune in to Brand’s Rumble show daily, either live or within a few hours of its stream, many of them specifically seeking out this relatively niche platform just to watch him. Despite his public protests about YouTube, the switch away won’t have been risk free: Brand would likely have been making most of his revenue—perhaps hundreds of thousands of dollars monthly—on the platform (and will still be generating tens of thousands there since he switched). YouTube is also the home of his already committed viewership and is a far better platform for gaining new viewers. A Rumble representative said the company would not answer any questions relating to its partnership with Brand.

Despite Brand’s undeniably substantial audience, then, what makes him individual in this crowded space—and particularly potent—is his pre-existing fame. This is what Felix Simon, a communication researcher at Oxford University’s Internet Institute (OII), says is key to Brand’s influence. “The most important thing to understand about people like Russell Brand, and online influencers in general, is that they are able to build something we call a ‘parasocial interaction’ with audiences,” he tells me. “Basically, they suggest to people that they are close to them and that their audiences and their fans are somehow their friends, who get to see them as they really are.”

This is where Brand is light years ahead. For most internet personalities who promote or platform conspiracy theories or harmful content, building up a name takes years. Their reputation grows over time and is linked exclusively to their online persona; they aren’t known for anything else. What makes Brand different is that he achieved A-list global fame nearly two decades ago. The average person online doesn’t need to be convinced of who he is—they already know. He can skip the crucial step of building familiarity, placing him on something of a fast-track to influence. “It creates this notion and illusion of actually knowing this person… and therefore makes people more susceptible and more trusting of the content these people provide,” Simon says.

Another pillar of Brand’s influence is the frequency of his work. Not only does he stream daily on Rumble and upload almost as regularly on YouTube, but he also posts clips of his content from these channels on TikTok and Instagram and releases a new, usually hour-length podcast called “Stay Free”—which is typically a recording from his Rumble stream—every weekday. This volume of content was unusual even before the relaunch, in May, of his weekly football podcast “Football is Nice”. A team of eight volunteers is mentioned on his site and he has a handful of producers on his podcast, though the exact number isn’t publicly available.

In this world, where conspiracy theories are scattered among reasonable discussion, volume matters. “Online radicalisation occurs when people engage more and more with this content,” says Anna George, a social data science researcher at the OII, “so by posting every day, and also having an archive on these platforms, it means that people are more likely to be radicalised.” But personality can also play a part.

George tells me that figures who can evoke an emotional response in their followers are additionally effective at creating this parasocial relationship and building trust; Brand “paint[s] himself as a trusted news source,” she says. Positioning himself in contrast to the mainstream media and the government, “he starts to sow doubt”. His followers “don’t trust these other sources and they begin to rely on people such as Russell Brand and others that he paints as having the true news”. George adds that Brand’s TikTok channel was a notable source of Covid-19 misinformation—in 2022 he was forced to retract a claim that the drug ivermectin was an effective treatment—with millions of people viewing and tens of thousands of people sharing videos that promoted false information. One study even called him an “opinion leader” on the pandemic.

Brand’s way of speaking, warmth and humour are also why he’s so compelling—you can see why people get hooked. He connects with others on a human level and seems to speak with rather than down to them. He makes his points like a friend making a joke over dinner, as if you’re already on the same page, and he has a style of humour that rarely veers into ranting and carries a calm, personable tone.

He is often mocking—in a video from May 2021 on the “vaccine gold rush” he imitates Bill Gates scratching his head and says, laughing: “I’m not an expert on body language, but I think that either this means ‘I’m lying’ or ‘I’m in Laurel and Hardy’”. In fact, he is almost always laughing, emphasising how plainly absurd he thinks whoever his target is (he reserves a more serious tone for anti-vaxxers such as Robert F Kennedy Jr and Dave Rubin, whom he has had on his show).

Brand can also be subtle in the way he approaches certain subjects, shrouding conspiracy theories in a veil of accepted truths and skirting around outright endorsement of misinformation. In his video mocking Bill Gates, he implies that pharmaceutical companies were interested in producing vaccines for “power, profit and control”, and also mentions criticisms of Big Pharma—such as its hoarding of vaccines and refusal to create universal patents—that would be widely considered valid. “Surely you would have to agree that if you did think vaccines were the solution, you would want as many people as possible to have access to vaccines—unless, of course, what you were primarily concerned about was power, profit and control,” he says. The greed of corporations for profit and the efficacy of the vaccines they produced are not mutually exclusive propositions, but this is not the complex reality Brand is interested in portraying.

Often, rather than outwardly saying he believes something that is known to be false (though he does also sometimes do that too), Brand will simply talk about someone else who is arguing in favour of a conspiracy, or will interview a person who promotes these ideas. He takes on the tactic of “just asking questions”—one example can be found in a recent episode of his podcast where he interviewed author Bjørn Lomborg, who believes the impacts of man-made climate change are overblown and there are bigger problems the world must tackle. Though Brand says at one point that there is evidence that climate change is man-made—something he also spoke passionately about in his Newsnight interview—he then allows Lomborg to speak for nearly an hour on findings from a study whose authors say Lomborg has “recklessly” misrepresented their work.

This powerful combination of pre-existing fame, a large volume of content and a knack for tapping into emotion is extremely uncommon—neither Simon nor George can cite another celebrity with Brand’s level of global fame who has pivoted in this way. But George says that while it is “always difficult to assess the impact” of figures similar to Brand, “one way is what these people are bringing in as valid conversation points—how the discussion on X topic changes.” She gives the conversation around Covid vaccines as an example. Suggesting that vaccine mandates were “a form of control” is the kind of behaviour that “then changes the vaccine debate to that idea being something to consider. Even if you don’t believe vaccines are a form of control, you have to give weight to it… It brings these fringe ideas into mainstream conversations.”

“These figures are known already—they have some kind of authority,” Simon adds. What they say “then gets picked up by other news media: ‘There’s this formerly known figure or actor who is spewing conspiracy theories on his streaming channel’… That’s the biggest problem, in my view,” he says. “That extends the reach of the message.”

People like Brand “are trying to reach everyday individuals that you otherwise wouldn’t think could be radicalised by this topic,” adds George. “I think it can happen to anyone.”

It would be easy to suspect that, like Brand, his typical follower is white, male and (streaming from the shed in his garden) isolated. But both George and Simon say that fans of conspiracy theorists, or shows that platform them, don’t fit one stereotype.

This lines up with the people who you see replying to Brand’s YouTube videos and in his Instagram comments. While there are some of the single men you might expect, his followers appear to range evenly across ages, genders and walks of life (although they do seem, at least from their online profile pictures, to be overwhelmingly white).

One unlikely fan is Francesca, a 26-year-old video editor based in the Midlands, who attended “Community” last summer—Brand’s weekend-long wellness festival in Hay-on-Wye. The festival is described on Brand’s website as “three days of camping, conversation on spirituality, wellness, healthy living and our environment. Limber up for yoga or Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, enjoy musical performances, relax with meditation and massage from a range of holistic healers on site.” Attendees last year included Wim Hof, who popularised ice baths and wild swimming as treatments for everything from depression to chronic autoimmune illnesses and is also known for promoting dubious Covid remedies. The fitness coach Joe Wicks was also (somewhat inexplicably) there. This year, adventurer Bruce Parry and musician Nick Mulvey are on the lineup. Standard tickets start at £225, but attendees can spend up to £995 on a bell tent before even considering the hundreds of pounds’ worth of merchandise, food and supplemental activities available to purchase (such as a River Wye canoe ride). Profits from the festival go to Brand’s recovery and addiction charity, Stay Free.

“I love going to wellbeing and spiritual festivals, and this seemed to have all the elements I look for,” Francesca tells me. “I liked the people he had on the lineup, namely Wim Hof… Also the very fact that it centred around ‘community’. I think that sense of true community is often lost in today’s world, as we spend every day consumed by social media and other distractions. I really liked the idea of being present with likeminded people.” She says she believes Brand is “very genuine” and that he brings people together “in a positive way”—that a true community atmosphere is cultivated among his fans. When I ask if she would go to the festival again, she tells me she has already bought tickets to attend this year.

Brand’s spirituality and openness about his own personal struggles attract a wider audience. Dan, a mid-30s caregiver based in the UK who asked to be identified via a pseudonym, tells me: “His appeal for me is down to his honesty with dealing with issues he has had in the past with mental health and addiction,” he says, noting that Brand’s exaggerated presenting style adds entertainment value. “Sobriety is a journey,” another fan, Carrie Goetz, tells me. “All of the things that touch our lives make us who we are and he does so unapologetically.”

Goetz, 62, is at the other end of Brand’s fan spectrum: a tech entrepreneur and author based in Florida who is an ardent believer in Brand’s worldview. (I initially came across Goetz on Reddit, where I saw her commending Brand’s individuality in the comments on a post entitled “I used to hate this guy. But I think I love him now”—a common sentiment among his recent converts.) Though she found Brand funny during his Hollywood heyday, she didn’t keep up with his career. She only began following him when she stumbled on his account online several years ago—now she watches his videos regularly on YouTube and Instagram.

“He possesses the power of critical thinking,” she tells me. “I like the humanism of his show… I love anyone that can think for themselves. When you listen to the regurgitated news, it is so refreshing to hear someone that can apply critical thinking. So many people simply follow along, and we are worse off for it.”

When I ask his fans about the conspiracy theories that Brand so often promotes, none are particularly concerned—in fact, they see his willingness to “question authority” as a main part of his appeal. “Everything I have watched from him is either clearly opinion or information pulled from mainstream sources,” Dan argues. “I don’t think this is any different from any other news or current affairs source.”

“I think people are very quick to call something misinformation,” Francesca says. “Just because someone is explaining a different viewpoint or opinion that differs from what they push on the news, immediately it’s like, ‘OMG he’s pushing conspiracy theories!’. It amazes me that people just believe everything they are told, like there’s never a hidden agenda. I believe Russell is just expressing other points of view.”

Goetz agrees. “In a world full of lemmings, no one likes a fox, dog, bird or any other animal,” she says. “If you aren’t pissing someone off, you aren’t doing much, as they say. No one is going to agree with 100 per cent of what anyone says if they have a functioning brain… More power to him, I say.”

People like Brand are trying to reach everyday individuals that you otherwise wouldn’t think could be radicalised

Yet the puzzle behind Brand’s rise is trying to find out: what does he truly believe? His fans commend his sincerity, but few note how often he evades giving his real opinion, merely propping up others to give theirs. While some have been fans of his comedy for years, no one I spoke to—on or off the record—said they agreed with the broadly leftist views he voiced 10 years ago. No one seems to question whether they’re being taken for a ride.

“It’s the question of intent,” Simon tells me at the end of our conversation. “How much of it is intentional and how much of it is unintentional, and what the motives are behind this…” He points to a separate example—the recently settled defamation case in which the Rupert Murdoch-owned channel Fox News agreed to pay $787.5m to the voting machine manufacturer Dominion. The company said its business suffered as a result of Fox spreading the false claim that the 2020 election had been rigged against Donald Trump. In the weeks preceding the settlement, it was revealed that some of Fox’s most famous anchors thought some of the claims they themselves were pushing were unbelievable and “insane”. “We know a lot of the Fox News hosts who spread Trump’s lies and propaganda actually did not believe what they were saying,” Simon tells me. “It was basically for attention and for audience views. And the question is: is Russell Brand someone in the same camp?”

It’s impossible to know whether Brand really believes the things he says or if he has had a genuine change of heart, having been radicalised himself in the past decade. But could his approach over the past 10 years have been a ruse, each new phase little more than a fresh attempt at seeking influence and attention? It may well be that, in changing his anti-establishment views to meet new audiences over time, his true interest has been less about the ideas themselves and more about shifting the Overton window, as a means to reclaim relevance—keeping the name “Russell Brand” synonymous with “the fringe philosopher who always manages to stay in the main frame”.

We can see a nod in this direction in a video posted to Brand’s YouTube channel in July 2021, where Brand himself rewatches his Newsnight interview, cutting in with present day reflections on what happened and how his thinking has changed. In the moment where he describes not caring about being taken seriously, just wanting to have his ideas heard, he becomes animated and pauses the interview.

“That is quite good that,” he says, referring to his response to Paxman. “People will try to mug you off, stripe you up, trip you over, by doing things like ‘I’m trying to take you seriously, why should I take you seriously?’ so that they’re defining the frame at that point as ‘you’ve got to be taken seriously.’

“Here, in a microcosm, Jeremy Paxman tries to establish the terms of engagement and I—through I guess dear, dear, dear sweet lady instinct—was able to go ‘I reject that idea’ and move forward,” he says.

“I reject your frame.”