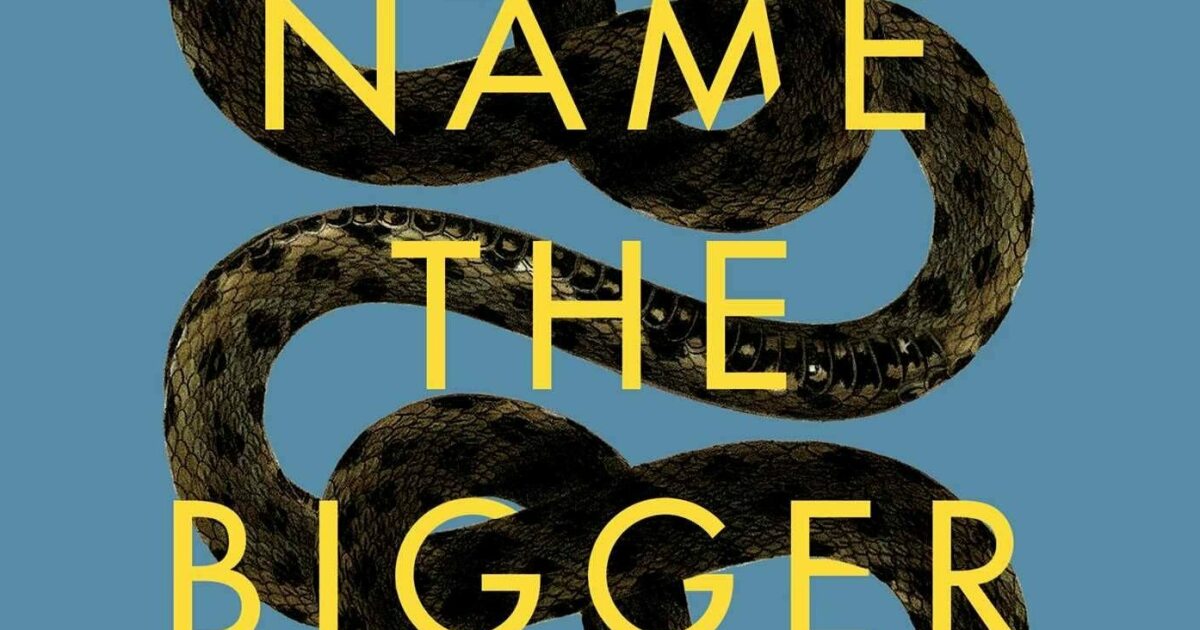

‘To Name the Bigger Lie’ is an investigation of the nature of truth

In March 2020, Sarah Viren published an essay in The New York Times Magazine that arrested the attention of more than a million people.

In it, she told the story of how her wife Marta — like Viren, a professor at Arizona State University — was anonymously accused of sexually harassing female students in 2019. The Title IX complaints were part of a smear campaign against the couple from a man who was competing with Viren for a creative writing professorship at the University of Michigan. Viren and Marta quickly discovered that this was the truth — but they needed the facts to prove it.

The essay — which has now become part of her memoir To Name the Bigger Lie — is gripping in part because it combines a detective story with a Kafkaesque nightmare of becoming tangled in academic bureaucracy. Crucially, throughout, Viren reflects on the relationship between truth and facts, and how facts can “tell different stories depending on who is picking them out and placing them in a narrative line.” This layer of rumination on lies, honesty, and nonfiction storytelling takes the essay beyond a rehashing of wrongdoing and into a deeper exploration of how easily fact and fiction can blur — a topic that should matter to us all.

When Marta was accused, Viren was already working on a book — one that would be a philosophical reckoning with the truth. She had planned to write about her high school philosophy teacher, a man who taught his students to question everything — a worldview that easily accommodated conspiracy theories. Dr. Whiles, as Viren calls him, became a cult figure for some of her peers, and she wanted to write about how “his influence over us complicated easy narratives about who can be hoodwinked and who unveils the truth” in “an allegory of sorts” to explain the post-truth Trump years.

But, as Viren writes, “One story can easily interrupt another, just as questions build one atop the next.” She revised her book project, layering the story of the false Title IX allegations atop the story of Dr. Whiles’ deceptions to form To Name the Bigger Lie. As she traces both men’s lies and how they skewed her understanding of reality, she simultaneously launches an investigation of the nature of truth. The memoir has the page-turning quality of a thriller, but instead of tracking down culprits and solving mysteries, Viren methodically untangles knotty philosophical tensions in pursuit of what is real.

To Name the Bigger Lie unfolds in four parts, each taking its title from Plato’s Allegory of the Cave from The Republic, a favorite of Dr. Whiles, and each consciously presented as a “story.” The first, “Strange Prisoners You’re Telling Of,” transports the reader to Viren’s public high school in Tampa, Florida, where she attended a magnet program in the 1990s. Freshman year, they were meant to learn research and critical thinking skills, but Dr. Whiles ignored the curriculum, opting to treat it as an introduction to philosophy rooted in asking mind-bending questions. Early in the school year, he gestured to the clock on the wall and asked if it existed, and if so, “can we confirm it exists outside our perception of it?”

As teenagers, Viren and her peers were primed to buy into that skepticism. The story that held the greatest appeal was that of Plato’s cave. Viren and her peers recall Dr. Whiles telling them this allegory rather than having them read it; later, she’d realize that his version was quite different from Plato’s. In both versions, a group of prisoners are chained to the floor of a cave, watching shadows on a wall cast by a fire that they can’t see. The prisoners think that the shadows are reality, until one, freed from his shackles, walks toward the cave’s mouth, where he is blinded by the light of the truth. Fifteen-year-old Viren immediately identified with the story: “High school often felt like a cave anyway: all of us trapped behind desks…staring at chalkboards filled with lessons we were told to accept as true, often without understanding them first.” But she struggled to escape the cave and figure out what was true, a struggle that Dr. Whiles’ teaching only compounded.

Viren structures this first story around her coming to terms with what the actual cave of her high school years was. She writes of how Dr. Whiles ratcheted up his sharing of conspiracy theories when he taught her class again their junior year, alluding to the Illuminati, the New World Order, and MKUltra. She writes of beginning to doubt Dr. Whiles when he “gave us the answers instead of asking us to figure them out ourselves.” That doubt burst to the fore one day when Dr. Whiles aired only one half of a debate about the Holocaust — the side that denied it.

As Viren reconstructs her teacher’s lies, she threads her storytelling with subtle commentary on truth, honesty, and narrative. When relaying a scene where she lied to her mother as a teenager, for instance, she writes, “Lying separates you from another person, briefly, temporarily, by creating one reality they believe and another you know is true.” The effect is to remind the reader that Viren is not actually reproducing the reality of her high school years — an impossible task — but consciously shaping the narrative, prodding us toward the mouth of the cave.

The second part of the book, “Would His Eyes Hurt and Would He Flee?” brings us up to the present, opening with a deepening Viren’s New York Times Magazine essay that further contextualizes and reflects on the story of the accusations. The anonymous lies, from a man Viren calls Jay here, once again shook her conception of reality. At the time, Viren had just received a job offer from the University of Michigan and the school was searching for a spousal hire position for Marta; the accusations put it all in jeopardy. She began to suspect that Jay — someone she knew casually because they were “both queer writers working in the academy” — was the culprit, because of texts he sent her.

In the version of this story that Viren has updated for To Name the Bigger Lie, she weaves in references to the lies and conspiracies of her high school years. Bringing together the two stories allows Viren to further her exploration into the ease with which one’s sense of the truth can be upended. “All you need us for one person to start lying, and a system — a high school, an investigation, a government — to legitimize that fiction,” she writes, diagnosing how deceit sows doubt.

Viren largely resolves the Title IX story a little more than halfway through the book. What remains to be unraveled, though, is why both men lied, what to do about their lies, and how to live in a world where the barrier between fact and fiction is so flimsy. That this part of the book is just as engrossing as what comes before speaks to Viren’s gift for making the stakes of philosophical questions pressing, for turning Plato and Socrates and Schopenhauer and Hannah Arendt into characters in her story about how to make sense of this world. Because To Name the Bigger Lie, in the end, is not merely about exposing the falsehoods of the Dr. Whileses and the Jays of the world, but about how the stories we tell shape our reality.

Kristen Martin is working on a book on American orphanhood for Bold Type Books. Her writing has also appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Believer, The Baffler, and elsewhere. She tweets at @kwistent.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.