The Titanic Truthers of TikTok

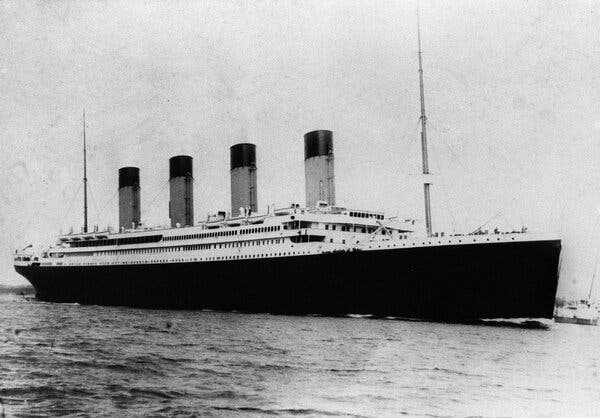

The finer details of what happened to the RMS Titanic differ depending on who is telling the story.

The iceberg that collided with the luxury liner was spotted at 11:40 p.m., according to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, or 11:35 p.m., which is what an exhibition about the ship in New York claims. The Royal Museums Greenwich in Britain says the doomed vessel cost 1,503 people their lives, while the Smithsonian in the United States claims that 1,522 passengers and crew died.

Historians have attributed the variance to factors like imperfect ticketing lists and rushed head counts transmitted using weak signals. The broad strokes, however, are not in question. All credible experts agree that on April 15, 1912, less than a week into its maiden voyage, the Titanic ended up at the bottom of the North Atlantic Ocean.

More than a century later, on TikTok, a far different version has been circulating. In a post that garnered more than 11 million views before it was removed earlier this year, one user wrote: “the titanic never sank!!!”

On the short-form video app, long-established facts about the crash are being newly litigated as musty rumors merge with fresh misinformation and manipulated content — a demonstration of TikTok’s potent ability to seed historical revisionism about even the most deeply studied cases.

One 32-second post opens with a dramatic black-and-white drawing of the Titanic, its stern straining above waves studded with people, set to a spooky synthesizer tune. A man in a hoodie and a backward baseball cap, crudely green-screened into the frame, makes a familiar argument (accompanied by an emoji of a screaming face): “The Titanic NEVER actually sank.” Looking into the camera, he repeats the so-called and exhaustively disproved “swap” theory — that the ruins on the seabed belong to the Titanic’s older and decrepit sister ship, the Olympic, scuttled in an attempt at insurance fraud.

Another video presents a conspiracy theory that the wreck was a “hit job” ordered by the financier J.P. Morgan — whose real name was John Pierpont Sr. — to eliminate opponents of the Federal Reserve.

Titanic skepticism has irritated scholars of the ship since it sank. Then, in December, came the 25th anniversary of the 1997 film “Titanic,” the costly and heartthrob-minting epic that laid a swooning romance over a fictionalized depiction of the disaster.

The celebration included a rerelease of the film in theaters just before Valentine’s Day. There was also a flurry of news reports about James Cameron, the director, working with scientists and stunt people to resolve a persistent debate about a pivotal scene in the movie, which centered on how many star-crossed lovers could survive on a door floating in freezing ocean water. (Tests showed that two could have, in fact, managed.)

Mr. Cameron’s experiments seemed to add fuel to a raft of TikTok conspiracy theories about the actual Titanic — many of them patched together from a grab bag of suppositions and misinterpreted evidence and posted in quippy online installments.

“It becomes kind of deflating to see a lot of this junk coming out,” said Charles A. Haas, a founder of the Titanic International Society who has spent six decades studying the ill-fated vessel. He co-wrote five books on the topic, dived down to the wreck site twice and debunked more conspiracy theories than he cares to count. “I feel like one of the very few voices crying out against the sound of a hurricane.”

The Titanic International Society, one of several historical organizations worldwide dedicated to Titanic study, has Instagram, Facebook and Twitter accounts but no presence on TikTok. Mr. Haas attributed the decision in part to the fear that TikTok’s reputation as “kind of a wild and woolly place” would taint any serious research shared on the platform.

“If you have a wonderful piece of filet mignon and you wrap it in smelly fish, the filet mignon after a while doesn’t smell so good either,” he said.

TikTok is just the latest recycling bin for false narratives about the Titanic, which began circulating almost as soon as the ship had sunk.

A month after the wreck, The Washington Post raised the possibility that the tragedy stemmed from the “ancient malice” of a mummified Egyptian priestess, who cursed an editor after he dared to tell her story to fellow Titanic passengers. Others have tried, unconvincingly, to pin the high death toll on Winston Churchill, a German submarine, sabotage-minded Catholic shipbuilders or decks that could be electromagnetically sealed to prevent passengers below from escaping. The Freemasons were accused of orchestrating a cover-up.

Such conspiracy theories are a fount of deep and familiar exasperation for Mr. Haas, fueled by years of weary disbelief that tall tales about an extensively documented disaster can continue to find audiences through books, so-called documentaries and now, a video app.

“The sad part is that many of the people following this sort of thing are teenagers, and they are woefully unwilling to do digging,” he said.

TikTok, which claims to have 150 million American users and is particularly popular with youths, has become an especially powerful vector for misinformation, past and present. A period of violent dictatorship in the Philippines decades ago was recently recast on TikTok as a rosy time of economic growth. A pawnshop owner on the app claimed last year to have an album of previously unseen images of the Rape of Nanjing in 1937, but later said that the disturbing photos, which drew nearly 52 million views, were actually “reproduction souvenirs” from Shanghai.

Like other social media platforms, TikTok has tried to tamp down some harmful historical falsehoods, such as efforts to deny the Holocaust, while working to combat more modern lies about elections, health hacks and other topics. (The company, which is owned by the Chinese internet company ByteDance, has also been fighting for its future in the United States amid national security concerns.)

“Our priority is to protect our community, which is why we remove misinformation that will cause significant harm and work with independent fact checkers to help assess the accuracy of content on our platform,” said Ben Rathe, a spokesman for TikTok. According to its guidelines, the company prevents some videos with conspiracy theories from showing up in feeds, like those that claim “covert or powerful groups” carried out events. But the app doesn’t block these videos altogether.

While many of the young users on TikTok can recognize and poke fun at conspiracy theories, the generation also struggles with understanding the past. Proficiency in U.S. history among eighth graders has declined every year since 2014, according to one federal gauge. Another poll last year asked whether NASA astronauts had landed on the moon — nearly half of the participants who were born after 1997 said they had not or that they were unsure.

In a recent survey of young Americans who use TikTok for more than an hour a day, 17 percent “couldn’t say definitively that the Earth is round,” according to the Reboot Foundation, a Paris-based nonprofit that promotes media literacy and critical thinking.

“Fundamentally, a 14-year-old is probably taught at school that the Earth is round and probably believes it, but with the frequency of watching videos over and over, they start questioning it,” said Helen Lee Bouygues, who started the Reboot Foundation to help fight misinformation. She said the group saw that “the longer young adults were on TikTok, the more that they believe what they see.”

Misinformation experts say that TikTok’s algorithm and the personalized feeds it creates for users can make it particularly powerful for spreading conspiracy theories. To show content to users, the system relies less on social connections and followers, like on Twitter and Facebook, and more on engagement, said Megan Brown, a senior research engineer at New York University’s Center for Social Media and Politics.

“If someone is spending time on a video, it doesn’t matter if they really believe J.P. Morgan sank the Titanic, or if they believe, hey, this is a funny video, someone is talking about J.P. Morgan sinking the Titanic,” Ms. Brown said. “This is the same signal as far as TikTok is concerned, so they recommend more of that content.”

Mr. Morgan, whose White Star Line owned the Titanic, figures prominently in Titanic lore. TikTok videos repeat decades-old claims that the millionaire backed out of a planned trip on the Titanic minutes or hours before it set sail because he intended to use the ship to assassinate powerful enemies onboard who opposed his efforts to create a centralized banking system. (In some tellings, TikTok creators have recast the villains as the wealthy Rothschild family or even the Catholic order of the Jesuits.)

Experts point out that the historical record and common sense do not support such assertions. Evidence suggests that Mr. Morgan failed to make his date with the Titanic because he was dealing with an unexpected situation involving his European art collection. The businessman would also have had to ensure that the Titanic would strike an iceberg with catastrophic force, and that his opponents were not among the more than 700 people who survived the crash.

Of course, history is not set in stone — especially when record-keeping was less technologically advanced — and experts often disagree. Parks Stephenson, a Navy veteran who has visited the wreckage multiple times and advised Mr. Cameron on a 2003 documentary about the ship, conflicts with many fellow Titanic scholars in his belief that the iceberg damaged the ship’s bottom rather than its side.

The consensus, though, is this: The Titanic sank in a terrible accident and many people died. Acknowledging the ship’s true fate allows the tragedy to become a valuable tool, Mr. Stephenson said: a way to understand communications failures, improvements in safety regulations, oceanic science, underwater forensics and hubris and heroism in times of crisis.

“On a grand scale, the study of history keeps you from repeating the mistakes that were made in the past and, continually, moving forward,” said Mr. Stephenson, who is now the executive director of the USS Kidd Veterans Museum.

Titanic conspiracy theories may seem relatively harmless, especially in a modern environment where online lies have enabled real-world harm, such as an attack on the Capitol or a gunman in a pizzeria. Untrue rumors about a 111-year-old shipwreck fall into something of a gap for social media companies, which are already struggling to address contemporary falsehoods with content moderators.

Ms. Brown said that the concern was a longer-term erosion of the truth and the idea that “people who believe in at least one conspiracy theory tend to believe in at least more than one.”

Hooking someone with one false narrative makes it easier to snare them with another, she said: “Hey, if you heard this about the Titanic, then you won’t believe this other cover-up.”

In the absence of TikTok intervention, some users have taken matters into their own hands.

Rafael Avila, 33, a tech consultant for IBM, is known in his spare time as “Titanic Guy” on TikTok, where he has amassed more than 600,000 followers since 2020 and frequently posts videos debunking conspiracy theories about the shipwreck.

“These theories have always been around inside the Titanic community, but they’ve sort of been on the fringe,” said Mr. Avila, who lives in Toronto and has been obsessed with the Titanic since childhood. TikTok changed that, he said. “When the first couple of videos were made about the Olympic theory, the Federal Reserve theory, the algorithm picked up on that, seeing that people were engaging with that, and then it started exploding.”

While Mr. Avila had joined the app to share his passion for the Titanic story, he quickly added debunking videos to his repertoire, using TikTok’s easy-to-use editing tools — like the ability to “stitch” or “duet” videos that promote bogus ideas to fact-check them. Now, his followers often tag him whenever a Titanic conspiracy theory video goes viral, so he can roll up his sleeves and film the facts. The TikTok videos with the truth don’t receive as many views as the intrigue-filled conspiracy theories, but they can still attract millions of eyeballs, he said.

“My community of Titanic nerds look to me to correct the record, so I’ve taken it on as my responsibility,” he said. “It’s the internet, people can say whatever they want.”