Why do some people believe in conspiracy theories? – study

Conspiracy theories – including who murdered US President John Kennedy in 1964, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995, Socialist Zionist leader of the Yishuv in 1933 Haim Arlosoroff, as well as who really was responsible for the September 11th attacks – have been common. But with the spread of social media, belief in them has been rampant.

Advocates claim that sinister, powerful and often political groups are guilty of certain acts even when other explanations are more probable. The theories’ appeal is promoted by conviction, prejudice, emotional conviction or too-little evidence.

Now, researchers at Emory University in Georgia have shown that people who believe in and spread conspiracy theories have a combination of personality traits and motivations including relying strongly on their intuition, feeling a sense of antagonism and superiority toward others and perceiving threats in their environment.

The study was just published in the American Psychological Association’s journal Psychological Bulletin under the title “The Conspiratorial Mind: A Meta-Analytic Review of Motivational and Personological Correlates.”

The results of the study paint a nuanced picture of what drives conspiracy theorists, according to lead author and Emory doctoral student Shauna Bowes. “Conspiracy theorists are not all likely to be simple-minded, mentally unwell folks – a portrait that is routinely painted in popular culture,” she said. “Instead, many turn to conspiracy theories to fulfill deprived motivational needs and make sense of distress and impairment.”

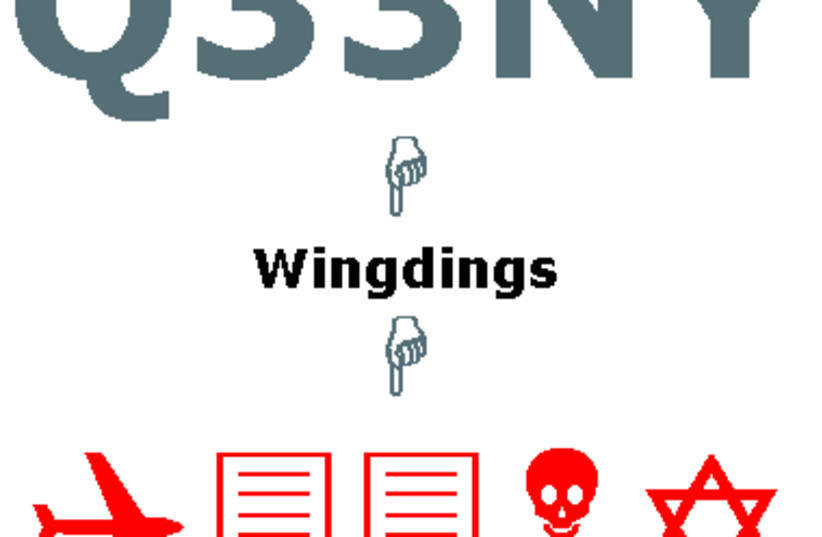

Example of a hoax distributed on Internet after the September 11 attacks. (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Example of a hoax distributed on Internet after the September 11 attacks. (credit: Wikimedia Commons)Previous research on what drives conspiracy theorists had mostly looked separately at personality and motivation, Bowes said. Her research involved the examination of these factors together to arrive at a more unified account of why people believe in conspiracy theories.

To do so, she and her team analyzed data from 170 studies involving over 158,000 participants, mainly from the US, the UK and Poland, that focused on studies that measured participants’ motivations or personality traits associated with conspiratorial thinking.

Why do people believe in conspiracy theories?

The researchers found that overall, people were motivated to believe in conspiracy theories by a need to understand and feel safe in their environment and a need to feel like the community they identify with is superior to others.

Even though many conspiracy theories seem to provide clarity or a supposed secret truth about confusing events, a need for closure or a sense of control were not the strongest motivators to endorse conspiracy theories. Instead, the researchers found some evidence that people were more likely to believe specific conspiracy theories when they were motivated by social relationships.

For instance, participants who perceived social threats were more likely to believe in events-based conspiracy theories, such as the theory that the US government planned the Sept. 11th terrorist attacks, rather than an abstract theory that, in general, governments plan to harm their citizens to retain power.

“These results largely map onto a recent theoretical framework advancing that social identity motives may give rise to being drawn to the content of a conspiracy theory, but people who are motivated by a desire to feel unique are more likely to believe in general conspiracy theories about how the world works,” said Bowes.

The researchers also found that people with personality traits like a sense of antagonism toward others, high levels of paranoia, being insecure, paranoid, emotionally volatile, impulsive, suspicious, withdrawn, manipulative, egocentric and eccentric were more prone to believe conspiracy theories.

Bowes said that future research should be conducted with an awareness that conspiratorial thinking is complicated and that there are important and diverse variables that should be explored in the relations among conspiratorial thinking, motivation and personality to understand the overall psychology behind conspiratorial ideas.

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from The Jerusalem Post can be found here.