‘Under the Eye of Power’ Review: Why We Love a Conspiracy

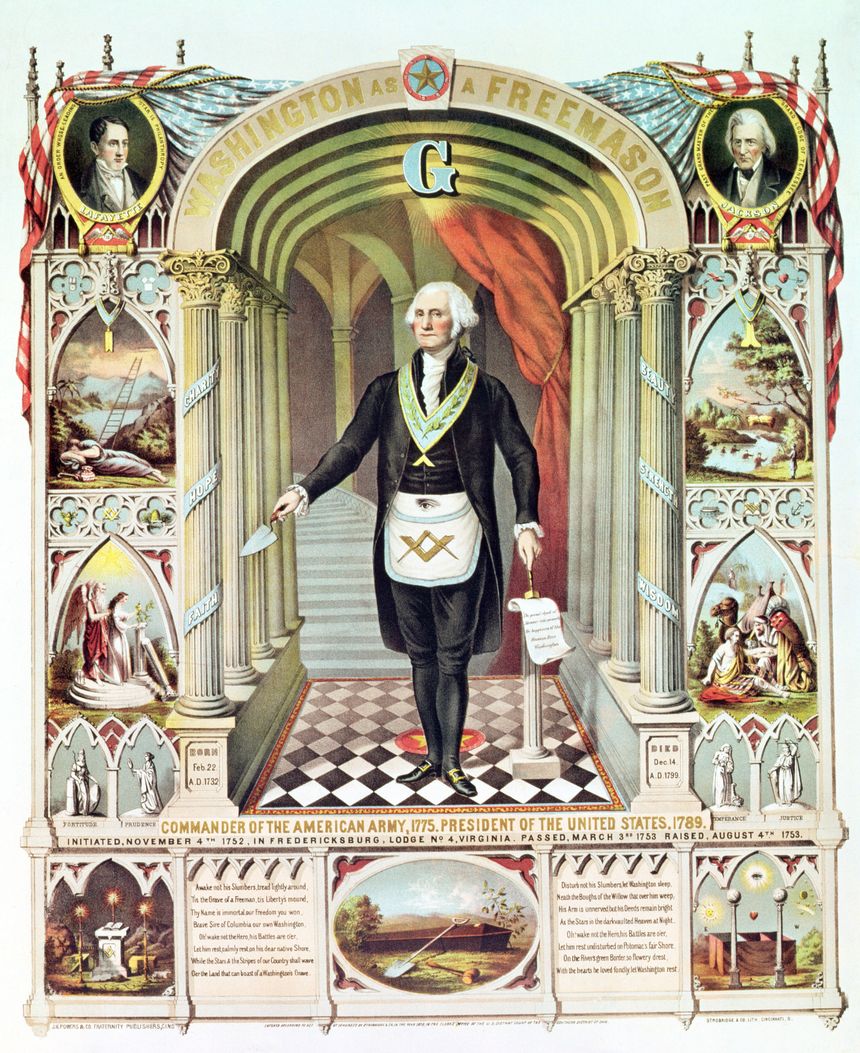

‘Washington as a Freemason’ (1870) by Strobridge and Co.

Photo: Bridgeman Images

In “Under the Eye of Power,” a timely book about the spread of conspiracy theories, the writer Colin Dickey argues that pseudo-secret narratives “have been a hallmark of American democracy from its inception.” Take George Washington: His transition “from an uneducated plantation owner to the head of a new nation cannot be entirely disentangled from his involvement in Masonry,” Mr. Dickey writes, invoking the secret society that is a perennial wellspring of conspiracy maundering.

That was then. And now? “RFK Jr.’s White House Bid Is a Mix of Nostalgia and Conspiracy Theories,” this newspaper reported last month, citing Robert F. Kennedy’s Jr.’s suggestions that “Wi-Fi exposure leads to cancer” and that the Central Intelligence Agency assassinated his father.

Mr. Dickey’s books “Ghostland” (2016) and “The Unidentified” (2020) explored American fascinations with the supernatural and paranormal. “Under the Eye of Power” takes on historian Richard Hofstadter’s famous 1964 essay on the “paranoid style” in American politics. Mr. Dickey insists, contra Hofstadter, that conspiracy fabulations are not fringe or marginal events in U.S. history. “You have to be able to see American history as a series of panics,” he writes, highlighting the Salem witch trials and Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s Cold War anti-Communist crusade. “These two events, held up as outliers and anomalies, were just two points on a straight line composed of a dozen similar points.”

To buttress his thesis that “conspiracies and moral panics are the great unseen engine of the country,” Mr. Dickey offers many examples, some well-known and some less so. The Freemasons, who originated as a trade association, were used to “explain” the American Revolution (Benjamin Franklin, like Washington, was a Mason). Freemasonry’s rituals were copied by other not-so-secret societies, including the Ku Klux Klan and the anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant, 19th-century Know-Nothing Party, whose slogan “Americans must rule America” sounds depressingly familiar.

Mr. Dickey highlights the many shared traits of supposed conspirators and their doctrines. For instance, it’s not always important that a secret society exist, as long as it’s believed to exist. Describing the Molly Maguires, 19th-century, pro-labor agitators, Mr. Dickey writes that, “We cannot even say definitively that they existed at all—at least as an organized conspiracy.” That’s because most of our information about them comes from a not necessarily reliable Pinkerton agent. But the Molly Maguires’ purported existence was useful to the enemies of organized labor. “You needed a place where the facts were simply unknowable and where in absence of facts you had nothing but beliefs,” according to Mr. Dickey.

Like religious dogmas, conspiracy theories are, Mr. Dickey notes, “untouchable by the normal laws of open scrutiny.” A case in point would be the spurious, anti-Semitic “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” a calumnious confection of the czarist secret police that resurfaces even to the present day. “Certainly they are a forgery,” the poet Ezra Pound said of the Protocols; “that is the one proof we have of their authenticity.”

Mr. Dickey is a lively writer, and it’s interesting to read how similar conspiracy tropes resurface throughout history. One is the lurid notion of sexual depredations conducted in basements. Sometimes these were imagined in the bowels of religious institutions, as in a bestseller from 1836, “Awful Disclosures of the Hotel Dieu Nunnery of Montreal.” There is a clear path from this supposed site of blasphemous goings-on to the Comet Ping Pong pizza restaurant in Washington, D.C., where gunman Edgar Welch fired off an assault rifle in 2016, thinking the pizzeria sheltered a cabal of child predators.

Even the phrase “I have a list” rings down through the ages. In 1799 Jedidiah Morse, attempting to link Thomas Jefferson with the quasi-mythological Illuminati, claimed to possess “an official, authenticated list” of the society’s officers and members. “Anticipating Joseph McCarthy by over 150 years,” Mr. Dickey comments, “Morse understood that you didn’t have to actually manifest proof if you loudly and repeatedly stated that you had it in your possession.”

One complication in creating a taxonomy of conspiracy theories is that some are true. The Federal Reserve, a frequent target of latter-day conspiracy mavens, was in fact created in secret, on an island, by a shadowy cabal of powerful bankers. “They were conspirators, but patriotic conspirators,” Roger Lowenstein wrote in his 2015 history of the Fed, “America’s Bank.”

Unfortunately, Mr. Dickey has a penchant to assign all conspiracy imaginings equal weight. It’s definitely noteworthy that many Americans follow QAnon, which he puckishly compares to Amazon; “its corporate growth strategy is to forever expand into new markets—sopping up new theories and seemingly unrelated anxieties and folding them into its endlessly expanding distributed network of paranoia.” But how many people really believe that beneath Denver’s airport there are, in the words of one conspiracy-monger, “large numbers of human slaves, many of them children, working there under the control of the reptilians”? Too few, I suspect, to merit our attention.

There are moments, too, when Mr. Dickey’s rhetoric seems to leap ahead of reality. Have we really “entered a period of epistemological crisis”? Has the world ever been easy to understand? He argues that conspiracy theories are “explanatory narratives for the unpredictable nature of modern life”—but why “modern”? His own book illustrates that many of the great conspiracy yarns, for instance those involving Freemasonry or the Illuminati, are hundreds of years old.

In the mind of the conspiracy theorist, Mr. Dickey writes, “there is no noise, just signal,” meaning that every aspect of every kooky idea is potentially “pregnant with meaning and direction.” But here comes Benjamin Franklin to argue that Freemasonry’s “GRAND SECRET is That they have no secret at all.” In other words, no signal, all noise.

Well yes, Ben, but what about that disembodied Eye of Providence hovering at the tip of the pyramid on our $1 bill? Perhaps, as Mr. Dickey playfully suggests, the famous Masonic symbol “is an insignia of a hidden group of conspirators, signaling . . . their plans for world domination, hiding in plain sight.” Or, perhaps it is a mirror of our own gaze, searching restlessly for the secret that explains it all.

—Mr. Beam’s latest book is “Broken Glass: Mies van der Rohe, Edith Farnsworth, and the Fight Over a Modernist Masterpiece.”

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from The Wall Street Journal can be found here.