Is the Future Really That Dark?

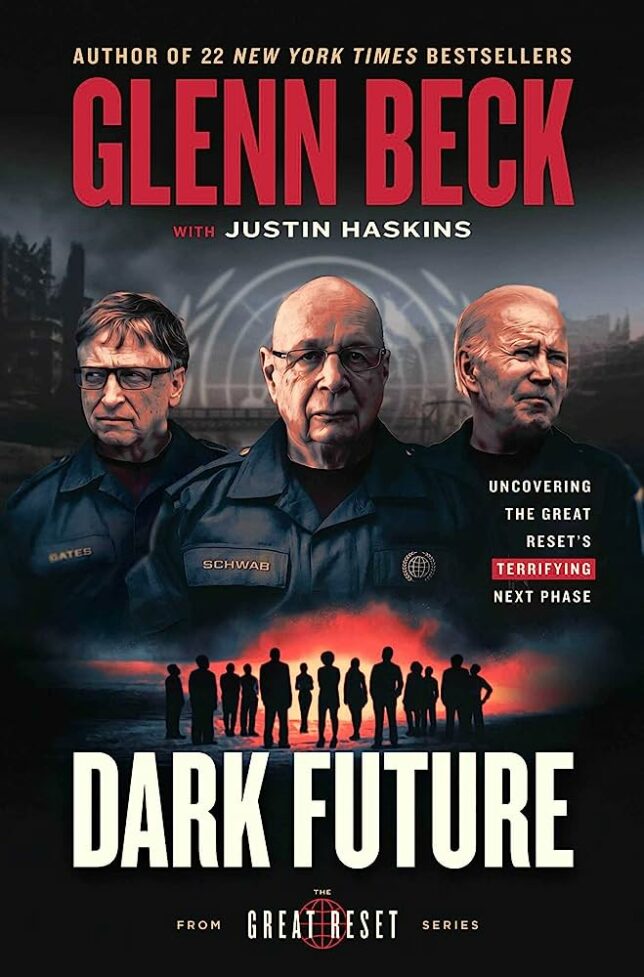

As the World Economic Forum’s (WEF’s) “Great Reset” and Forum leader Klaus Schwab’s “Great Narrative” attract increasing scrutiny, the critics of the WEF’s technocratic vision about whom I wrote back in January are increasing in number. Among the latest installments of criticism is Dark Future, a response to the Great Narrative by Schwab and coauthor Thierry Malleret authored by political commentator Glenn Beck with Heartland Institute research fellow Justin Haskins.

While Dark Future will likely bring awareness of the Great Reset and its critics to a wider audience (as of writing, it lies at number 18 on Amazon’s most-sold nonfiction chart, having debuted at number 12), those who have studied the World Economic Forum and Great Reset will hear many notes they have heard before. The book usefully discusses artificial intelligence and increasingly real questions about bioethics in human genetic manipulation, and it offers a deeper analysis of “national fascism,” the authoritarian model Russian autocrat Vladimir Putin has advanced (including by armed aggression) in opposition to the WEF’s multilateral-technocratic model.

But all told, the book misses more than it hits. And I have a suspicion as to why—a suspicion that applies not only to Dark Future’s authors but to many others on the American right.

Dark Future

Stylistically, Dark Future suffers from Beck’s overly conversational, talk-show-host writing style and unconnected presentation of facts. The book would have profited from tightening down to a target length of 300–350 pages of substantive text rather than its 430 and focusing more closely on its argument rather than seemingly disconnected fact-dumps.

That said, the book does provide some depth in its criticism of what it calls “international fascism” (WEF-style multilateral technocracy) and its comparably bad rival, dubbed “national fascism” (the authoritarian model of Putinist Russia and Communist China). Its dissection of Putinist ideology and caution to American traditionalists that Putinism is not their friend is also welcome. The book is also diligent in avoiding making factual assertions it cannot substantiate; this is not a conspiracy-theory tome.

The Error

But I think the Dark Future authors and many others overestimate the power of conservatives’ adversaries, and that makes the future about which they warn appear much darker than it likely will be. Let us consider two case studies.

- Beck and his coauthor draw attention to the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, an ESG activist coalition of major financial-industry firms seeking to uphold the Paris Climate Accords, calling its establishment “the Great Reset movement’s greatest victory yet.” If that is the case, that victory could be quite hollow, as even the slightest pushback from conservative governments (red-state attorneys general, in this case) caused one of its constituent coalitions, the Net-Zero Insurance Alliance, essentially to collapse.

- Beck warns that the model of “you’ll own nothing and be happy” is coming to pass in the housing market. But while major investment houses like Blackstone Group may be buying up residential properties, even Beck admits that data compiled by the Federal Reserve show the home-ownership rate within its normal historical range (if below the pre-2008 financial crisis high). If we are to own nothing by 2030, time is running out for that number to move.

It seems like the “designed” world that Beck and his coauthor warn the World Economic Forum is trying to build may not be coming to pass. And at least in the period before artificial superintelligence may be developed, the old warnings from thinkers like Friedrich Hayek about the limits of central planners’ knowledge still hold.

Move and Countermove

The “national fascists” in Russia and China are not the only resistance to the agenda associated with the World Economic Forum. When voters are faced with the reality of “Bunch’s Law” that “environmentalists make good movie villains because they want to make your real life worse,” they often choose to reject it. Just last week, Britain’s Labour Party blew a chance to embarrass the country’s embattled Tory government by taking former Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s vacant London-area seat in a special election (“by-election” in UK political speak). And a Great Narrative–aligned policy scheme may have been to blame.

The Tory candidate seems to have held on against national wave conditions aimed at his party in large part because the Labour Party, which runs London’s local government, has enacted the unpopular Ultra-Low Emissions Zone rule restricting private car use. The Telegraph quotes a London School of Economics professor stating, “Politicians who underestimate the power of the car—and the use of cars and the freedom that cars bring and as a driver of votes—do so at their peril.” The War on Cars claimed a political victim unlikely to be its last.

In Dark Future, Beck and his coauthor present an end to private car ownership (a nearly explicit WEF policy goal) as functionally inevitable because of ESG investment pressure, government regulation, and the power of corporations like Uber and Lyft. But is it? It is one thing for a state like California to promise to much fanfare that it will ban internal-combustion vehicles 12 years from now. But it is another to expect the government to go through with taking away a convenience some 91 percent of households have come to expect for their own good. Just ask any Republican who has attempted to reform Medicare or Social Security in the past couple of decades how well that tends to go at the ballot box.

The Gods of the Copybook Headings

Shortly after the end of the Great War, British author Rudyard Kipling (perhaps best known for The Jungle Book) published “The Gods of the Copybook Headings,” a poem reflecting on the tendency of eternal wisdom (incarnated in the form of the eponymous “gods,” the proverbs schoolchildren would memorize) to prevail over the contemporary “Gods of the Market Place,” modern political wishes and slogans.

I contend that the story of the Great Reset and Great Narrative has been and will continue to be not a Dark Future but rather the Gods of the Copybook Headings once again prevailing over the Gods of the Market Place. The Great Reset itself was predicated on predictions about the COVID-era and post-COVID economy that did not come to pass. Klaus Schwab and his conversation partners’ predictions about the inevitable triumph of the digital world over the physical in a Fourth Industrial Revolution are challenged by the insufficiency of digital substitutes for corporeal life we experienced during the period of lockdowns and restrictions. Like the resurgence of car-rental firm Hertz that Schwab did not predict, the “old normal” has more resilience than Schwab or Beck likely expect.

In my analysis of the Great Narrative, I wrote that “The technocratic vision has a critical flaw: It admits no decision point at which policymakers or the mass public must decide whether to bear a cost for a benefit.” Technocrats and the Federal Reserve might wish to control consumer choice by adopting central bank digital currencies, but will legislatures given the power “To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin” go along with them at the point of decision? Artificial intelligences may process quantities of data presently incomprehensible, but what is done with that data will be subject to political scrutiny.

And what of the global governance that Beck fears and Schwab proclaims? It never existed, and it will not exist anytime soon. To quote Kipling: “The Gods of the Copybook Headings with terror and slaughter return”—the terror and slaughter being quite literal in the fields of Ukraine.

Beck concludes his book with a call to readers to fight Schwab’s Great Narrative and keep America the “shining city on a hill.” To which I say that for all America’s problems, it has been, even in recent times. The worldwide opposition to COVID lockdowns did not emerge in Europe (with acknowledgment to Sweden’s noble refusal to enact the harshest forms of lockdown). It grew from a trickle in the South Dakota State Legislature to a stream in Georgia to a river in Florida until the electorates of Virginia and Long Island demonstrated to policymakers that there would be consequences if the resistance was not heeded.

All is not yet lost; the future need not be dark.