How Have Conspiracy Theories Changed History?

‘Walpole clung to power by shrieking about treacherous schemes cooked up by his rivals’

Joseph Hone, author of The Paper Chase: The Printer, the Spymaster, and the Hunt for the Rebel Pamphleteers (Chatto & Windus, 2020)

The 17th century was an age of conspiracies. It was also an era in which discerning real conspiracies from imagined ones was extremely difficult. There were no fact-checking agencies. Many plots did occur, but some of them did not. And, to make matters even more complicated, some of them sort of did and didn’t at the same time.

The most infamous of 17th-century conspiracy theories, the ‘Popish Plot’ of 1678, was a hoax fabricated by a pair of down-and-out grifters. Yet it was also the result of deeply ingrained fears that Catholic fifth columnists were secretly plotting to bind England once more to the yoke of Rome. And, in a sense, those fears were well founded: when Charles II signed the secret Treaty of Dover with Louis XIV in 1670, it included a clause requiring his conversion to the Catholic Church.

A decade later, when Mary of Modena birthed a male heir to the Catholic James II in 1688, the accusation of a wicked plot once more reared its ugly head: the infant was rumoured to be a lowborn babe, snuck into the bedchamber in a warming-pan. The queen had not even been pregnant. It was all a ruse to ensure a male Catholic heir to the Stuart dynasty.

The immediate effects of these conspiracy theories were very real. The ‘Popish Plot’ resulted in new anti-Catholic legislation, dozens of executions, and the drawing-up of party-political battle lines that would last for a generation. However, perhaps the deepest legacy of these conspiracy theories was that they provided politicians with a coherent rhetorical framework centred on opposition subterfuge, which, as the historian Mark Knights has shown, had important and long-lasting consequences for the structure of British politics. The passage of the Septennial Act in 1716, extending parliamentary terms from three to seven years, was justified by the need for national stability against a barrage of conspiracies and plots, some of them real but more of them imaginary. For the next 25 years, Robert Walpole and his Whig oligarchy clung to power by shrieking about the treacherous schemes being cooked up by their rivals.

‘The theory of a global papal conspiracy persists’

Jessica Wärnberg, author of City of Echoes: A New History of Rome, Its Popes, and Its People (Icon, forthcoming)

The ‘Papal Octopus’ first appeared in the 19th century, representing in cartoon form an all too familiar conspiracy theory. From Rome, a monster wearing an egg-shaped crown extends tentacles of tyranny and superstition: the pope is a supranational power choking the sovereignty and values of countries across the globe.

The ‘Papal Octopus’ was invented by Americans who identified Catholic immigrants as menacing papal minions. Yet angst about the global reach of the papacy began much earlier. In the 11th and 12th centuries, rulers clashed with pontiffs over who chose the bishops who guided the people of their lands. Ultimately, the popes won the dispute. Pope Innocent III claimed his power was like the sun while that of the Holy Roman Emperor merely reflected it like the moon. Beyond the Papal States, however, papal influence was increasingly more feared than real. Even on the Italian peninsula, papal interventions were often rebutted. Early modern Venice made peace with the Ottomans rather than fighting them as part of Gregory XIII’s Holy League.

By the time the ‘Papal Octopus’ appeared, the pope was politically marginalised. In 1870, Pius IX declared himself a prisoner in the Vatican as Rome was seized as the capital of the young Kingdom of Italy. Many Catholics lamented; some fought as Papal Zouaves. But globally, the president of Ecuador offered a near-lone voice of political support.

Despite its increasing baselessness, the theory of a global papal conspiracy has had consequences. During the First World War, some leaders dismissed Benedict XV’s interventions for peace as attempts to regain political power. We cannot know if the pope’s involvement would have changed the course of that conflict. We can, however, conclude that fear of the ‘Papal Octopus’ has only exacerbated the loss of papal power.

Remarkably, in some quarters, the conspiracy persists. In April 2023, Chinese president Xi Jinping broke an agreement with the Vatican by electing his own Catholic bishop in Shanghai. Xi’s action continued historic efforts to exclude papal influence from China, estranging China’s ten million Catholics from the Church to which they have belonged for centuries.

‘Not every conspiracy theory is necessarily a con’

David Armitage, Lloyd C. Blankfein Professor of History, Harvard University

A conspiracy theory doesn’t have to be true to change the course of history: it just has to be convincing. Theories make sense of the incomprehensible by turning disparate data into meaningful facts. Conspiracy theories stir in ideas of intention and agency.

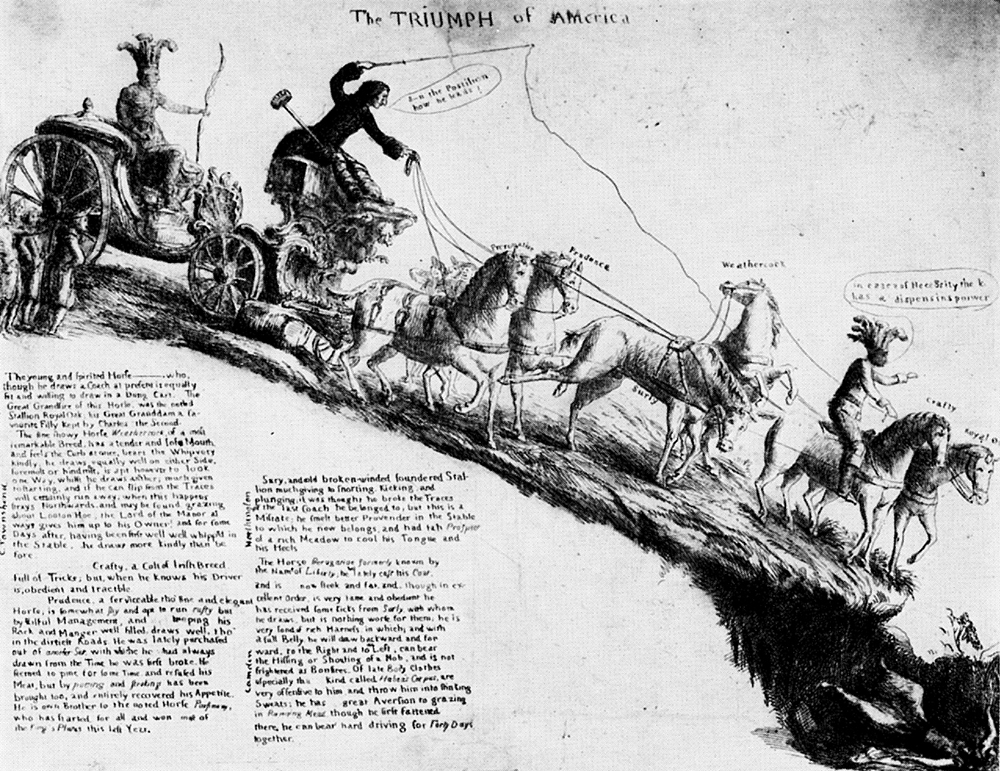

One example of a conspiracy theory changing history can be found in the run-up to the American Revolution. In the aftermath of the Seven Years War, with France defeated and in retreat, Britain’s rulers faced up to the hangover of global conflict: ballooning debt, increased defence spending and novel responsibilities in the Americas, including new Catholic subjects in Quebec. Settler colonists in the older parts of Britain’s American empire, from the Caribbean to New England, resented increased taxation and tighter protectionist policies coming from London, especially from Parliament. Congregationalist Protestants also feared the imminent erection of a colonial bishopric and suspected Quebec as a bridgehead for Romanism in North America. Starting during the Stamp Act Crisis of 1765 and gathering steam in the following decade, white settler rebels dusted off 17th-century slogans to decry popery and, above all, ‘slavery’ in the evil designs of Westminster and even – in the most perfervid imaginings of Thomas Jefferson – George III himself.

After armed resistance broke out in British America, the Continental Congress issued a series of documents laying out nothing less than a global conspiracy against liberty directed first against the American colonies, then spreading to Ireland, the British Caribbean and South Asia. In response, many Britons believed a parallel conspiracy: that excitable descendants of Puritans and Roundheads were hellbent on independence from the British Crown and Parliament. The collision of conspiracy theories inflamed and propelled divisions on both sides of the Atlantic, to form what the great early American historian Bernard Bailyn called ‘the ideological origins of the American Revolution’. The colonists’ fears may have been overblown and their invocation of ‘slavery’ hypocritical; meanwhile, metropolitan Britons’ prophesies became self-fulfilling in July 1776. Yet both showed that not every conspiracy theory is necessarily a con: to be actionable it just has to be credible.

‘Distrust of public institutions provides fertile ground for conspiracy theories’

Victoria Pagán, Professor of Classics at the University of Florida

Tiberius, the emperor who succeeded Augustus in ad 14, only had one son, so he adopted his nephew Germanicus as a ‘spare’. Unfortunately, Germanicus became so popular with the populus that he began to make Tiberius and his son look bad. Perhaps because of this, Tiberius sent Germanicus to Syria, removing him from public life. The statesman Piso was also sent, ostensibly to assist Germanicus.

Piso was trouble. He was disrespectful and countermanded Germanicus’ orders. Then Germanicus fell gravely ill. Strange things were found in their camp: remains of human bodies, spells and curses, tablets etched with the name ‘Germanicus’. Publicly, Germanicus blamed Piso for poisoning him, but privately he admitted that he feared Tiberius was behind his impending death, which came in October AD19.

Piso returned to Rome, where he was found guilty of treason (which he did not commit) but not of murder. Piso attempted to defend himself but was attacked by senators and rebuffed by Tiberius. That night he wrote a few words, handed them to his freedman, and ordered his bedroom door closed. In the morning, he was found with his throat slit, a sword nearby.

We are left with two dead bodies and no transparent explanation for their deaths. Conspiracy theories blossomed. Tiberius had machinated the murders; senators were complicit in protecting the emperor; Piso’s wife had planned it all. It is possible that Germanicus died a natural death and that Piso died by suicide.

The historian Tacitus tells us that Tiberius ‘could scarcely hide his joy at the death of Germanicus’. The conspiracy theories surrounding the deaths of Germanicus and Piso contributed to Tiberius’ reputation for tyranny and violence. Given its opaque, hierarchical structure, Roman imperial politics was a hotbed of conspiracies. Germanicus and Piso’s deaths may not have radically changed history – only our perception of Tiberius – but the affair illustrates how distrust of public institutions provides fertile ground for conspiracy theories, the spread of which only damages faith in those institutions further. This, of course, is as true today as it was in the ancient world.

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from Google News can be found here.