In U.S., most UFO documentation is classified. Not so in other countries.

RIO DE JANEIRO — Early one August evening in 1954, a Brazilian plane was tracked by an unidentified object of “strong luminosity” that didn’t appear on radar. Two decades later, a river community in the northern Amazon jungle was repeatedly visited by glowing orbs that beamed lights down onto the inhabitants. In 1986, more than 20 unidentified aerial phenomena lit up the skies over Brazil’s most populous states, sending the Brazilian air force out in pursuit.

The stories are not the ravings of a UFO buff. They are official assessments by Brazilian pilots and military officers — who often struggled to put into words what they’d seen — and can be found in Brazil’s remarkable historical archive of reported UFO visitations.

Even more extraordinary? It’s all public record.

There are no security clearances. No heavily redacted documents. Anyone can access the files — the military reports, the videos and audio recordings, the grainy unverified photographs — and thousands of people have.

“It’s comparatively easy to get this information here,” said Rodolpho Santos, a historian at the Federal Institute of Minas Gerais. “And the variety of records is good and considerable.”

Brazil and the United States are two countries of continental proportions, frequent UFO sightings and active communities of extraterrestrial enthusiasts. But how each has responded to the most fundamental of human questions — are we alone? — has been sharply different. In the United States, the matter of unidentified aerial phenomena has often been treated as a closely guarded government secret. Meanwhile, in Brazil and much of South America, there has been a more relaxed attitude toward the inexplicable, the public’s right to know and the limits of scientific explanation.

Now, as legislators in Washington push for the same transparency that other parts of the world have enjoyed for years, the cultural and nationalistic differences between how countries interpret the skies and what is divulged have grown even more apparent.

In South America, at least four countries — Uruguay, Argentina, Chile and Peru — have public government programs that study and investigate UFO activity. Argentina and Chile regularly release reports on identifying aerial objects. And in Uruguay, which has passed UFO details along to the United States since the 1970s, the military runs the Commission for the Reception and Investigation of Complaints of Unidentified Flying Objects.

“We have been sharing the information with the public since the beginning,” said Col. Ariel Sánchez, the head of the Uruguayan program. “We believe people need to be informed.”

Whether a country shares that contention, researchers say, often comes down to military interests. The United States, for example, has often been less willing to publicize or publicly engage on questions about UFOs — even going so far to spread misinformation in the 1950s — for fear of ceding a strategic advantage to adversaries and jeopardizing national security.

“The U.S. has always tended toward secrecy,” said Chris Impey, an astronomer at the University of Arizona. “Only in the last year or so has there been a push for transparency, but the backdrop of that was flat-out denial or secrecy.”

In Brazil, where polling shows that 33 percent of people believe in extraterrestrial life, ufologists are not treated as crackpots. They run magazines and operate through official-sounding organizations, such as the Brazilian Commission of Ufologists. Some were granted an audience before the Brazilian Senate last year and have met with some of the country’s most important military leaders. Generals, in turn, openly wonder about extraterrestrials without fear of derision.

“The science of man is very small to be able to explain all phenomena,” said Gen. Marco Aurélio Rosa. “And our cultural and ethnic mixing has enabled Brazilians to have this curiosity about the supernatural, the mystical and transcendental, that ends up leading us to the question of ufology.”

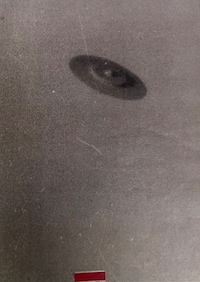

Brazil’s military began posing such questions in the 1950s, shortly after two journalists came back from an assignment in Rio de Janeiro with what they claimed were extraordinary photos. They showed a circular object flying over a granite mountain. One of the photos — now stored in the national archives — leaped onto the cover of the national magazine O Cruzeiro. “FLYING DISC,” the headline said. More sightings of other flying discs quickly followed. The public was restless for answers. The military launched an inquiry and then held a public conference in 1954 at its national academy in Rio de Janeiro.

Col. João Adil Oliveira, one of that era’s most respected officers, stepped in front of a large audience.

“The issue of flying discs,” he proclaimed, “is serious and deserves to be treated seriously.” The military had not been able to disprove the journalists’ photos, nor discern the disk’s provenance. (Years later, some ufologists asserted that the photos had been faked; the issue remains hotly debated by Brazilian enthusiasts.)

In the decades that followed, how the military treated reports of subsequent sightings was in large part a function of Brazil’s own vacillating commitment to transparency. During the military dictatorship, which ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985, most information was restricted. But when the country returned to democracy, and particularly after the 2011 passage of a freedom of information law, Brazilians availed themselves of their newfound right by requesting, first and foremost, access to UFO records.

By 2013, the military was deluged by requests, according to reporting at the time. The pile of information requests involving UFOs was nearly four times higher than the next largest — that involving military pay. With pressure building, then-Defense Minister Celso Amorim signed off on a meeting with Brazilian ufologists and afterward ordered the transfer of a vast trove of UFO records to the national archives for public access.

“I did it because of the demand at that time,” recalled Amorim, now a senior adviser to President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

For the first time, researchers and ufologists were able to scrutinize the most curious incidents in recent Brazilian history. Some proved to be frauds or were easily explained away. But regarding others, questions lingered.

One involved the impoverished Amazon community of Colares in the state of Pará. In the latter half of 1977, the community was gripped by panic. People were saying the region’s rivers had been invaded by flying, luminous objects. They beamed lights down onto people, who, according to military records, reported symptoms of paralysis and dizziness.

A military unit was sent in to investigate. It spent four months in the area. The team photographed the flying lights, interviewed dozens of people and wrote extensive reports that included drawings of the luminous aircraft that, in declassified notes, looked like flying American footballs. The military observers said that what they saw defied explanation.

“We feel as we haven’t come to a completely satisfactory conclusion,” João Flavio de Freitas Costa wrote in his November 1977 report. “The cases … left us in doubt and without explanations, based on our standards of knowledge.”

Other reports involved what would come to be known here as the “Official Night of UFOs.” It occurred in May 1986, when 21 separate flying objects were reported across southeastern Brazil. Dozens of people — perhaps thousands — witnessed the flying objects. One of those witnesses was a pilot who, while in the air, made a call to a control tower.

“I’m seeing three of them now,” the pilot said, according to the recording.

“Could it be a shooting star?”

“A shooting star that stands still?” he said. “It’s beautiful. It changes from red to yellow. … Look at them. I have chills.”

The military sent planes out to intercept the objects. Cmdr. José Pessoa Calvalcanti de Albuquerque tried to describe what the military and air traffic control witnessed in a confidential report dated June 2, 1986. “They are solid phenomena and reflect a certain intelligence,” he wrote, “by their ability to accompany and keep distance from observers and that they fly in formation.”

But even in a country largely open to discussing and inquiring into unidentified phenomena, not all matters have been fully disclosed. Missing from the archives, ufologists say, are military photographs and videos of the orbs that visited the Amazonian river community as well as military documents regarding perhaps the most notorious alleged encounter, known as the “Varginha Incident.”

In January 1996, three young women claimed they saw a bipedal creature while walking through a vacant lot in the southeastern city of Varginha. It was neither human nor animal, they claimed. The story sent the city of 140,000 inhabitants into a tizzy and spawned wild rumors. People alleged that it was an alien that, after the sighting, had been captured by the military and secreted away — allegations that Gen. Rosa said were false.

“The army does not have a piece of ET,” he deadpanned.

For years afterward, Kátia Andrade Xavier, one of the three young women, said she was ridiculed for her story. Few employers wanted to hire her. People, she said, called her crazy, a liar, demonic.

But now, with more countries asking more questions about UFOs, she said she is being received differently.

“People are seeing my story completely differently,” she said. “I feel realized. I am happy.”

Ana Vanessa Herrero in Caracas, Venezuela, and Marina Dias in Brasília contributed to this report.