Who’s afraid of Naomi Wolf? Naomi Klein’s newest book takes on her doppelganger

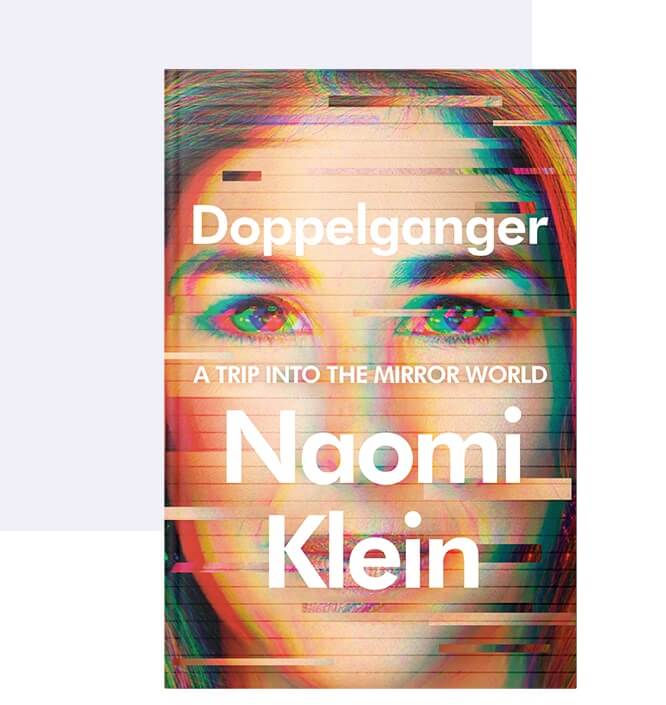

Throughout her life, Naomi Klein has been unable to escape confusion and comparisons with Naomi Wolf. Graphic by Getty Images/Mira Fox

Naomi Klein and Naomi Wolf are confused so frequently that the Wikipedia page for each woman links to the other. “Naomi Klein: Not to be confused with Naomi Wolf.” “Naomi Wolf: Not to be confused with Naomi Klein.”

“Other Naomi — that is how I refer to her now,” Klein writes in the introduction to her new book, Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World. “A person whom so many others appear to find indistinguishable from me. A person who does so many extreme things that cause strangers to chastise me or thank me or express their pity for me.”

Klein, a professor of climate justice at the University of British Columbia, has written about a wide range of progressive topics, including exposés of corporate abuse, critiques of capitalism and treatises on climate change. Her breakout book, No Logo, examined the power and ubiquity of corporate branding, and The Shock Doctrine delved into the way corporations and governments leverage disasters for profit and power.

Wolf, too, was once known for her progressive critiques; her 1991 book, The Beauty Myth, was a foundational text of third-wave feminism. Like Klein, she’s written about corruption and corporate abuse. She advised the Clinton and Gore campaigns. But today, she is better known for promoting conspiracy theories and fake news, particularly stories of anti-vax “persecution” during the pandemic, and for being a regular on Steve Bannon’s conservative radio show.

This sent Klein down a rabbit hole that resulted in Doppelganger, a very different kind of book from Klein’s previous, academic and activist works. In it, Klein combines literature, history and memoir to understand how she and Wolf went down such opposite roads — and how any person, ideology or historical event has a shadow self too.

Klein consumed anything she could find about doppelgangers. She goes through Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Philip Roth’s Operation Shylock and a good bit of Freud. She examines historical events, like how Dr. Hans Asperger went from being a researcher concerned with troubled children to a Nazi who condemned those same misfits to death. She explores how wellness culture can lead to eugenics, and how the pro-choice slogan of “my body, my choice” was co-opted by anti-vax activists.

And she realized that she and the Other Naomi are, perhaps, more similar than she wanted to admit. Both are suspicious of big corporations and government corruption, and they ask similar questions. And, unavoidably, there’s “the Jew thing,” she writes. “Wolf and I had always been lumped together inside a very particular cultural stereotype — that of the striving Jewess.”

This leads Klein to take on the ultimate doppelgänger for the Jewish Diaspora: Israel. The Sabra as the strong, tanned doppelgänger of the European Holocaust victim. Zionism as the opposite force of the Bundists’ value of diaspora. And Israel’s violence against Palestinians against Europe’s persecution of Jews.

“The doppelganger nature of the country’s identity is embedded in the dualistic language used to describe it, in which everything is double and never singular: Israel-Palestine, Arab and Jew, Two States, The Conflict,” Klein writes. “Based on a fantasy of symmetrical power, this suturing together of two peoples implies conjoined twins in a state of unending struggle.”

Klein is thorough in constructing her argument; she spends the final two chapters before Doppelganger’s conclusion scrutinizing Hitler, the Holocaust and the history of antisemitism, considering its connections to the emergence of Zionism and, finally, Israel’s current government.

It’s controversial territory, and not least because Klein opens by arguing that the Holocaust was not a singular event. For the past several years, Jewish groups have railed against any politician or activist who has called anything but the Holocaust a holocaust, defending the event as an experience belonging solely to the Jewish people.

But Klein unapologetically asserts that the Holocaust was one of many genocides. “The flip side of the post-World War II cries of ‘Never again’ was an unspoken ‘Never before,” she writes. “The countries that defeated Hitler did not have to confront the uncomfortable fact that Hitler had taken pointers on and inspiration on race-making and on human containment from them.”

(“Concentration camps were not invented in Germany,” Hitler said in 1941. “It is the English who are their inventors, using this institution to gradually break the backs of other nations.”)

Jews, she argues, were the target of the Holocaust because they are Europe’s doppelgänger: a dark, shadow self on which to project every problem. And this leads her to Israel, and its need for its own shadow self.

“Just as the Old Jews were trapped in a fraternal battle with European Christians, cast as devils onto which all evil was projected, so the New Jews required their own anti-self: The Palestinian,” she writes, “a locus of perpetual threat inside Israel and on its borders.”

Klein’s conclusions get a bit overly grandiose when she posits that Wolf was perhaps sent on her path to conservatism when she took a stand against Israel’s bombing of Gaza and was publicly decried by Jewish press, even losing her teaching post at Barnard over her political statements on Israel. Did losing a plank in her Jewish identity, Klein asks, “contribute to how unmoored she became in subsequent years?” It feels like an attempt to tie the book’s conceit together, and show why Israel is a good lens through which to understand her relationship with Wolf.

But she doesn’t need to prove why she needs to talk about Israel; Israel, in many ways, feels like the unavoidable culmination of the book. For many progressive Jews, Israel is an unavoidable double, a side of Jewish identity that it is impossible to extricate one’s Judaism from, however hard you may try.

“After all this mapping of mirrored selves and mirror worlds and fascist doubles, I find myself drawn to this place that for so much of my life has been my own Shadow Land,” Klein writes. “A place I have struggled with in public and in private and in my own highly divided family.” (Klein has family members who are settlers, and has herself visited and written about Gaza.)

Klein sees more than a cautionary tale in the story of Israel, though. As critical as she is of the Jewish state, she’s also critical of its detractors who are unable to recognize the legitimate need and trauma behind its founding. She delves into the rich Jewish history and thought that built Israel, and existed before it, and sees possibility for change — for a richer, more holistic Jewish identity that doesn’t require full-throated support for Israel or complete denial of it.

In doing so, Klein also lays the groundwork for a richer, more holistic understanding of identity at large. As Doppelganger comes to its conclusion, it feels as much like a treatise against cancel culture, or even a psychological work about integration of the ego as it examines our need to foist our baser impulses on a shadow self. It’s the same reliance on black-and-white thinking, she argues, that leads Wolf to Steve Bannon or Holocaust survivors to occupation.

The cautionary tale, she argues, is to ever believe that there is “just one answer” or to boil any situation down into a singular belief or brand. Instead, she says, we must accept “that a people, just like a person, can be victim and victimizer at the same time; that they can be traumatized and traumatizer.”

“All of this is true at once,” she writes. “If Israel-Palestine teaches us anything, it might be that binary thinking will never get us beyond partitioned selves and partitioned nations.”

Klein’s politics may be controversial, but this sentiment is, hopefully not.