Ross Douthat’s Theories of Persuasion

Ross Douthat’s Theories of Persuasion

September 11, 2023

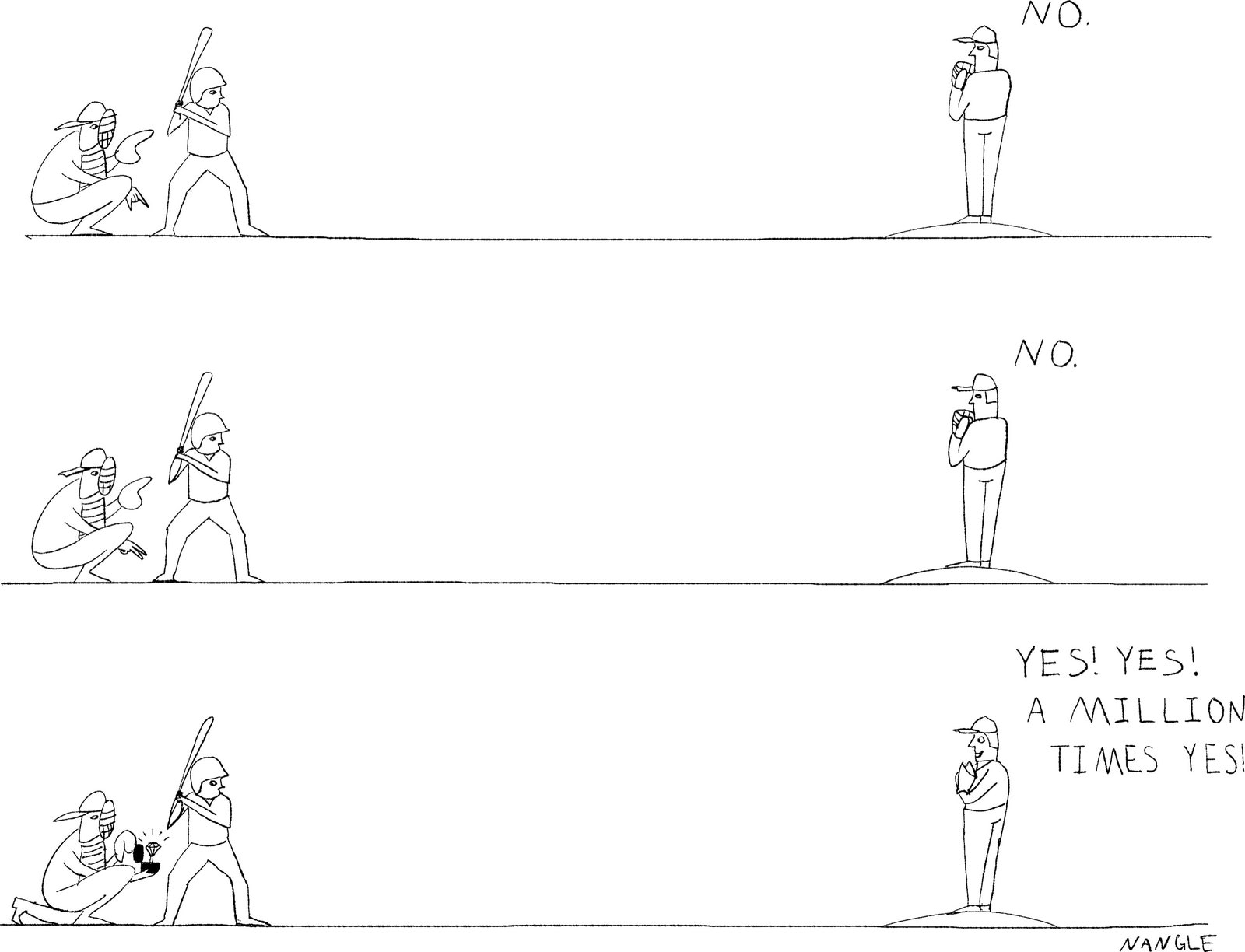

This summer, Ross Douthat, liberal America’s favorite conservative commentator, wrote a piece about liberal America’s least favorite Democrat, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. Douthat argued in his New York Times column that an unwillingness to debate Kennedy—who has claimed that childhood vaccines cause autism, that 5G networks are part of a mass-surveillance system, and that COVID was designed to spare Jewish and Chinese people—was an insufficient response to voters who are increasingly distrustful of the establishment. “If you don’t think he should be publicly debated, you need some other theory of how the curious can be persuaded away from his ideas,” Douthat wrote. “Right now the main alternative theory seems to be to enforce an intellectual quarantine, policed by media fact-checking and authoritative expert statements. And I’m sorry, but that’s just a total flop.”

Douthat is highly skilled at addressing liberal Times readers in a manner that makes clear he is not one of them, without allowing them to think that he actually holds views—about Donald Trump, say, or the importance of vaccines—that would render him beyond the pale. If asked to debate Kennedy, he continued, “I wouldn’t speak on behalf of the vested authority of science, but on behalf of my more moderate doubts about official knowledge, a much more cautious version of the outsider thinking that he takes to unjustifiable extremes.” In Douthat’s view, the widespread distrust of science and embrace of conspiracy theories about vaccines, among other topics, “hasn’t happened because of bad actors on the internet. It’s happened because institutions and experts have so often proved themselves to be untrustworthy and incompetent as of late.”

A few days after Douthat published the column, I met him for lunch at a dimly lit French restaurant in New Haven. We were joined by the leftist historian Samuel Moyn, who co-teaches a class with Douthat at Yale called “The Crisis of Liberalism.” “I have a bunch of what you might call conspiracy-adjacent views,” Douthat said with a grin, after I asked him how he’d come to write the column. “I think that the medical establishment is wrong about Lyme disease, because I had Lyme disease. This is not conspiracy-adjacent, but I think that nice secular people like you and Sam are sort of blind to some obvious supernatural realities about the world. I think lots of people have good reasons to end up in that kind of territory. And the question I don’t know the answer to is: Why is it so natural once you’re in that territory to go all the way to where R.F.K. is?” He continued, “I spend a lot of my own intellectual energy trying not to let my sort of eccentric views blind me to the fact that the establishment still gets a lot of boring, obvious things right.”

“In your case, some of the limits are characterological or temperamental, but aren’t some also professional?” Moyn asked. “Because I think of you as the conservative whisperer to liberals at the New York Times, and you have to remain credible.”

“I think that’s right,” Douthat responded. “If I wrote a flatly conspiratorial essay for the Times, it would get fact-checked and not published. There are also ways in which my vocation keeps me connected to the conservative coalition, because what am I doing if I’m not critiquing liberalism to some extent? It’s hard to separate your own fundamental beliefs from what you have structured your intellectual work around.”

Douthat is tall and burly, with a short but unkempt goatee. His hair began thinning years ago, so that he looked about forty-five when in his twenties—perhaps ideal for a young conservative on the make in Cambridge, Massachusetts, or Washington, D.C.—but now that he is actually in his mid-forties he appears relatively youthful. One way that Douthat tries to disarm progressive or secular interlocutors is by playing up his role as a conservative. He will joke about being part of a right-wing conspiracy, or about trying to convert you to his faith, Roman Catholicism. At lunch with Moyn, he complained genially about what passes for intellectual diversity at Yale: “You always have people saying, ‘Oh, So-and-So is very conservative.’ And what that means is that they only vote for Democrats, but they, like, study military history.”

Moyn smiled in such a way as to suggest that he’d heard this joke, or one like it, before. Moyn and Douthat have developed a rapport over their shared skepticism of prevailing wisdom, but for Moyn that skepticism exists within certain boundaries. Moyn recalled that, at the start of their course one semester, he’d said, “ ‘Look, this is actually a class that’s about a dispute within liberalism. Ross is a liberal, I’m a liberal. We’re just differently situated than current liberals or centrist liberals.’ And he took a lot of exception to that.”

Douthat looked a bit sheepish. “I think liberalism has strengths and weaknesses,” he said. “I think it benefits from critiques from both the left and the right. It needs them to work. I don’t see an alternative to liberalism available at the moment which is worth shattering society in order to obtain. But if you said, ‘Philosophically, are you a liberal?’ No, I’m not.”

Several times during lunch, I prodded Douthat on whether the right’s increasing distrust of liberal democracy is really the fault of liberal institutions. Perhaps a large portion of the right had turned into vaccine conspiracists who thought that Anthony Fauci belonged in prison not because of the failures of the élite, or because of natural human skepticism, but in part because of the media outlets that give airtime to Kennedy, or to Tucker Carlson?

When responding to such questions, Douthat often seems sincerely interested—out of some combination of self-preservation and genuine thoughtfulness—in phrasing his answers carefully. After a pause, he said, “Would I say that the New York Times should pluck someone from obscurity to write an op-ed saying that vaccines cause autism, because we find that five per cent of our readers think that, and they need to be represented? No, I would absolutely not say that. But the people who are making the argument already have a platform and an audience, so you need a way to engage it.” Douthat continued, “I think a lot of people in the world of The New Yorker and the New York Times decided in the Trump era that they didn’t even want to know where these ideas were coming from. It was just enough that they were bad. And I think you do have to figure out where those ideas were coming from.” Douthat was getting more animated; he smiled broadly, and waved his right hand in the air to emphasize his points. “What liberalism—élite liberalism, whatever you call it—doesn’t have is just a theory of persuasion.” He paused again. “That’s why, I mean, maybe I am a liberal if I’m interested in theories of persuasion.”

Douthat, who joined the Times in 2009, occupies an all but vanished position: he is a Christian conservative who lives among liberals, writes for them, and—even when he is arguing against abortion, or against “woke progressivism”—has their respectful attention. This is in part because he is curious, not only distraught, about the decline of faith in American life. For Douthat, the most interesting question is whether that decline will lead to, as he put it in a recent piece, “a truly secular America,” or “a society awash in new or remixed forms of spirituality,” from the post-Christian right to the post-liberal left (which practices “a variation on the Protestant social gospel”). He writes frequently about his own Catholicism and about the fate of the Church—he strongly opposes Pope Francis’s efforts at liberalization, especially regarding divorce and remarriage—but he is also fascinated by other forms of spirituality and by the supernatural, as well as, in the case of U.F.O.s, by the simply unexplainable. Douthat offers a counter-secular perspective—one that encompasses both the Catholic conservatism that currently rules the Supreme Court and the skepticism of science and tendency toward conspiratorial thinking that activates the political fringes.

In addition to his political commentary, Douthat generates a steady stream of columns on popular culture, especially film and television. (Since 2007, he has been the film critic at National Review.) For a social conservative, these are rarely fogeyish. Even his most pessimistic work—he wrote a book several years ago called “The Decadent Society,” which argues that American culture is essentially stagnant—seldom extends to critiquing works of art for their ethical failings. “He’s not a philistine, and he is interested in culture in ways that are not just oppositional,” Michelle Goldberg, his Times Opinion-page colleague, told me. “And he is such a creature of left-wing milieus, even if he is critical of them. I suspect that he is more comfortable in them than he would be in conservative milieus.”

James Bennet, the former editor of the Times Opinion page, told me that Douthat possesses “the ability to kind of think out loud in a nonthreatening way.” In this respect, Douthat is nearly the opposite of the Times’ best-known conservative columnist, David Brooks, whose musings on marriage, faith, and privilege routinely infuriate readers. “He has an amazing ability to make me feel envious,” Brooks said of Douthat, when we spoke by phone. “A lot of people can make broad points. A lot of people can dig up facts. But Ross just has a mind that allows his columns to be incredibly closely argued.” Other conservatives on the Times Opinion-page roster—the foreign-policy analyst Bret Stephens, the Christian legal scholar David French—frequently challenge Republican viewpoints, but Douthat is distinguished by how often he gives liberals a sustained hearing.

At its most basic level, Douthat’s popularity among Times readers and progressives can be explained by his long-standing critique of the Republican Party. Years before conservatives like Brooks, Stephens, and French were driven from the Party by Donald Trump, Douthat complained that it was in thrall to donors at the expense of a more family-friendly economic agenda. In 2008, he and Reihan Salam—then his fellow-columnist at The Atlantic, and now the president of the Manhattan Institute—published a book called “Grand New Party,” which argued that both parties had failed working-class voters, and that Republicans could win them over by focussing on tax cuts that were not aimed primarily at the wealthy and on support for working families.

Douthat was regularly mocked for believing that such a turn was possible for the G.O.P., especially as the Party became more extreme on fiscal issues during the Tea Party years. The liberal columnist Jonathan Chait once wrote that Douthat’s support of the Republican Party was “sort of like supporting la Cosa Nostra because you like the concept of a group dedicated to helping down-on-their-luck Italian-Americans. You can find bits and pieces of this behavior here and there, but it’s fundamentally not what la Cosa Nostra does.” Douthat, with his interest in conservative populism, could seem blind to its dangers: Sarah Palin, he wrote, in 2009, “represents the democratic ideal—that anyone can grow up to be a great success story without graduating from Columbia and Harvard.”

When the G.O.P. finally turned to someone who appeared to have little interest in privatizing Social Security or Medicare, that someone was a thuggish demagogue. Douthat has devoted extensive time to criticizing Trump, but he also saw his rise as a vindication of the ideas laid out in “Grand New Party.” “Trump was a yes-to-full-employment, no-to-welfare-state-rollback guy” Douthat told me. “He was the dark version of what Reihan and I were advocating.” (Brooks said, “What they got right was an emphasis on trying to be at least in part the party of the working class. And what they failed to foresee is how nasty that working-class party would turn out to be.”)

Douthat’s obvious disgust at Trump’s character comes through frequently in his column, but it exists alongside a desire to understand Trump’s appeal. Several weeks before the 2020 election, when many political observers were warning that Trump might deny the results and try to hold on to power, Douthat wrote a column titled “There Will Be No Trump Coup.” According to Douthat, Trump was “a feckless tribune for the discontented rather than an autocratic menace.” A year later, Douthat wrote that he stood by his assessment of Trump but admitted that he had underestimated the mob: “I didn’t quite grasp until after the election how fully Trump’s voter-fraud paranoia had intertwined with deeper conservative anxieties about liberal power.”

This was a generous reading of, for example, the people who’d built a gallows outside Congress. Douthat is comfortable being a “conservative whisperer” to liberals, as Moyn put it. Telling harsh truths to his fellow-conservatives is sometimes more difficult for him, in part because of his tendency to attribute right-wing paranoia to liberal missteps. Moyn told me, “His role is in part the apologist and rationalizer of the actually existing right, even as he idealizes a version of it that he would rather have.”

Michael Brendan Dougherty, a National Review columnist and a friend of Douthat’s, said that he and Douthat both see Trump as “this bad character.” But he also relayed a phone conversation that they had on Election Night, 2020: “Ross feels the genuine conservative Schadenfreude at liberal overreach and failure. During the early returns, the needle at the New York Times was bouncing all over the place. There was a genuine, Oh, my God, is it happening again? He was just laughing at our fate—possibly to be stuck with Trump again—but also at the potential failure of conventional wisdom.”

To Douthat, a second Trump term is not the worst-case scenario. He told me, “People organize themselves around dystopian fears to a deep extent, right? If your primary dystopia is a kind of fascist authoritarianism, you’re going to end up in a different alignment versus if your fundamental dystopia is something closer to Huxley’s ‘Brave New World.’ ” The latter—a secular state that manages sex, death, and reproduction—is Douthat’s dystopia, and in several of our conversations he brought up newly permissive euthanasia laws in Canada and other countries. He recently wrote, “In the Canadian experience you can see what America might look like with real right-wing power broken and a tamed conservatism offering minimal resistance to social liberalism.”

But Douthat reserves his greatest intensity for the matter of abortion. He acknowledges that, as he wrote in one column, “the pro-life movement’s many critics regard it as not merely conservative but as an embodiment of reaction at its worst—punitive and cruel and patriarchal, piling burdens on poor women and doing nothing to relieve them, putting unborn life ahead of the lives and health of women while pretending to hold them equal.” Yet, for Douthat, these concerns can be swept away, because, as he put it in another column, “a distinct human organism comes into existence at conception, and every stage of your biological life, from infancy and childhood to middle age and beyond, is part of a single continuous process that began when you were just a zygote.”

Goldberg, who has sparred with Douthat over abortion on podcasts, but says that she holds him in the highest regard as a columnist, told me, “He knows what the audience is, and so he tempers his views on sexual issues, where I think his views are probably more apocalyptic than comes through in his writing.” She added, “He will try to make fairly dispassionate arguments about abortion rather than arguing that abortion is morally monstrous—even though I think that is the belief motivating him. He’s developed a sly distance that has allowed him to make his genuinely reactionary sentiments seem slightly ironic when they are actually sincere.”

Michael Barbaro, the Times podcaster, has been a close friend of Douthat’s since childhood—he told me that he was Douthat’s “sidekick”—and was the best man at his wedding. In 2015, Douthat wrote a piece critical of the Supreme Court’s decision to legalize gay marriage, expressing concern that it reflected a “more relaxed view of marriage’s importance.” The two men were now colleagues, but they had drifted slightly apart over the years. And Barbaro was married to a man.

Barbaro said, “We hadn’t been in touch that much, but Ross reached out to me to say, ‘I’m about to publish a column in which I come out against same-sex marriage, and I want you to know that it didn’t come to me easily, and that it’s something I know may be sensitive to you. And, as somebody I care about, I want you to understand it, and I don’t want you to read about it in my column without us talking about it.’ ” Barbaro told me that he appreciated the note, which surprised me. I said that some people might have been more, rather than less, angry that the friend taking such a position saw that the issue went beyond abstraction. “I was wounded by the position he took on a personal level. How could I not be?” Barbaro said. “But it was meaningfully tempered by the reality that I knew where he was coming from, and that he had gone to the trouble to reach out to me.”

Barbaro and his husband later divorced; when we spoke, he was on vacation with his wife and two children. “I’ve been on a long journey that I know Ross generally approves of,” he said. “But, although I didn’t do it for him, it’s very funny, as I have had children I can just sense his glee. It’s no secret that he wants people to have children and to enter into monogamous heterosexual relationships.” Barbaro let out a laugh. “And that wasn’t my plan, but I have sensed his joy at that outcome.”

“I occasionally get accused of being part of the Wasp aristocracy of New England,” Douthat told me. “But that is unfortunately not the case.” His father, a lawyer and later a poet, came from California; his mother’s family, in Maine, is a mix of lobstermen, carpenters, and more bookish people—“garage-sale rummagers and self-conscious outsiders,” Douthat once wrote. He described going to an elementary school, in Connecticut, that “had a donkey and a lot of guitar playing.” Barbaro recalled that, as teen-agers, he and Douthat would say that they attended the “working-class private school” in the area. (The better-known Choate Rosemary Hall was nearby.)

Douthat said that he had a superficially “conventional liberal, Northeastern, upper-middle-class childhood,” but that his mother, Patricia Snow, suffered in ways that set the family apart. As Douthat wrote in a recent memoir about his Lyme disease, “The Deep Places,” “My mother had struggled with chronic illness when I was young, with chemical sensitivities and debilitating inflammation that had sent our family down a lot of strange paths—to health-food stores in the days before Whole Foods, to Pentecostalist healing services where people spoke in tongues, to chiropractors and naturopaths and other purveyors of holistic medicine.” Snow wrote about this journey for the religious journal First Things. She described being unable to sit in certain cars, “because of the new plastics and formaldehyde,” or to bear being in an enclosed space with another mother, because of “the chemical fabric softener in her laundry soap.” Snow became a follower of a charismatic healer named Grace, and brought the young Ross with her to services where people wept and fell to the floor in the aisles. She eventually turned away from Grace’s ministry, but only because her own faith had deepened. “All I knew was that to try to feed this hunger with the food of miracles didn’t work and could lead to sin,” she wrote.

To a child, Snow’s growing fervor could have been bewildering or tumultuous. But Douthat, by his own account, approached it then the way he might now, with respect and curiosity. “Whatever the reality of charismatic healing is—speaking in tongues and all these things—that reality was a hundred per cent present in a lot of the places where we went and hung out. There was nothing faked or fraudulent about it,” he told me. But, he added, “I would say I didn’t have dramatic experiences with the Holy Spirit. I was more a sort of observer of my mother and my father, of my mother’s religious pilgrimage.”

When Douthat was in high school, Snow converted to Catholicism—which, he said, came as a relief. “I was extremely happy to end up in a church where you memorized the prayers and you could sit in the back,” he told me. “The famous unfriendliness of Roman Catholicism was perfectly congenial to my sixteen-year-old self. The lack of spontaneity, the fact that there’s a ritual for everything, was quite welcome to me after this long charismatic sojourn.” Douthat converted as well, along with his father and his younger sister, Jeanne. He told me, “I had a conventional, ‘Read C. S. Lewis, read G. K. Chesterton, read some Catholic apologetics, find it persuasive,’ kind of experience, which was quite different from my mother’s more mystical encounter.”

Barbaro said, “The mother is where it’s at, in both good ways and bad ways.” When I asked what he meant by this, he explained that, when they were growing up, Snow “was always there, and had this big personality, and was deeply intellectual and deeply religious. I remember things in the house were a certain way, in terms of things like food. There was a particularness to the way that life had to be lived. People’s lives had to be a little bit oriented around her.” Snow does not have e-mail or use a cell phone, so Jeanne relayed my questions to her and then sent me pictures of her responses. I asked Snow how her faith differed from her son’s. She replied, “I think that Ross himself has commented on this in the past, describing my faith as more ‘pious’ than his (daily Mass, the occasional pilgrimage, and so on), and his as more cerebral, detached, and even perfunctory.”

Douthat, elaborating on the contrast with his mother, told me, “I think that ironic detachment, from a religious perspective, is my weakness. You don’t read about a lot of saints who have ironic detachment.” He added, “There’s distancing that I do from ideas that I do in fact hold. That’s part of how I’ve made my way as a writer in the world.” When I spoke to Douthat’s wife, the journalist Abigail Tucker, about his faith, she said, “He’s always kind of reaching and looking, without being religious in a rote kind of way. I think he wishes he was. I think he totally wishes that he had that always stable perspective. It must be exhausting.”

In 2015, Douthat and Tucker bought an eighteenth-century farmhouse in Connecticut, with pastures and apple trees. In “The Deep Places,” he writes, “I had a vision of myself going out into the world, flying around to various Babylons for important meetings and interviews, and then coming home on a summer evening, down a winding road, up a drive lined with oak trees, to find my two—no, make it three; no, make it four—kids waiting for me, playing on swings in the July dusk in front of a big white Colonial, my wife behind them, the whole scene an Arcadia.” But on one of their first visits to the property Douthat contracted Lyme, and what was undertaken in the spirit of an invigorating renewal became an enervating nightmare. (Douthat writes that he and Tucker joked that it was “just like ‘The Shining’—except we’re both writers.”)

Douthat describes his symptoms—pain, mostly—in agonizing detail. “It was a sense of invasion,” he writes. “Of something under my skin and inside my veins and muscles that wasn’t supposed to be there.” But “The Deep Places” is largely about his efforts to recover, which, in many respects, drew him closer to his mother’s world. Douthat reports that he has chronic Lyme, an illness that many physicians do not believe exists. He saw “the Maverick,” a doctor who’s willing to prescribe antibiotics for years beyond the standard Lyme treatment. He then went further still, experimenting with supplements, more antibiotics (obtained, at times, from veterinary pharmacies), magnet therapy, and a Rife machine, which is said to treat illnesses by matching their electrical frequencies.

Having Lyme transformed his thinking. “I am more open-minded about the universe than I was seven years ago,” he wrote in his column. “And much more skeptical about anything that claims the mantle of consensus.” It also, he said, deepened his faith: “So why does God let bad things happen to people and so on. When you’re not suffering, this seems like more of a hard intellectual problem. When you’re actually suffering, the intellectual puzzle goes away.” Several times in “The Deep Places,” he describes praying or calling out to God and receiving an answer, in the form of a sand dollar that appears on the beach, or the brief cessation of pain. Snow wrote to me, of her son, “I would say that his faith is more grounded than it was before in his mortal body (‘we hold this treasure in earthen vessels’), and at the same time, more mystical. Suffering, if it doesn’t rout your faith altogether, can do that to you.”

Since the worst years of his illness—which were followed by a tough bout of COVID—Douthat has been, in some ways, a different columnist. He’s written several times about U.F.O.s, and he’s made many references to Jeffrey Epstein, saying that he’s open to the theory that Epstein was a foreign intelligence asset. In one column, Douthat offered his own approach to assessing fringe ideas. “To be a devout Christian or a believing Jew or Muslim is to be a bit like a conspiracy theorist, in the sense that you believe there is an invisible reality that secular knowledge can’t recognize,” he explained. “But the great religions are also full of warnings against false prophets and fraudulent revelations. My own faith, Roman Catholicism, is both drenched in the supernatural and extremely scrupulous about the miracles and seers that it validates. And it allows its flock to be simply agnostic about a range of possibly supernatural claims.”

In recent years, a number of Catholic conservatives have been laying out alternative visions for how modern societies should function, with some offering praise for Viktor Orban’s Christian regime in Hungary, which has seized control of the press and of universities, and passed a number of anti-L.G.B.T. laws, including a ban on recognizing gender transitions. In a 2021 column about Hungary, Douthat expressed empathy for conservatives who admire Orban’s attempts to combat liberal culture. “It would be a good thing if American conservatives had more of a sense of how to weaken the influence of Silicon Valley or the Ivy League,” he wrote. But, he concluded, “the way this impulse has swiftly led conservatives to tolerate corruption, whether in their long-distance Hungarian romance or their marriage to Donald Trump, suggests a fundamental danger for cultural outsiders.”

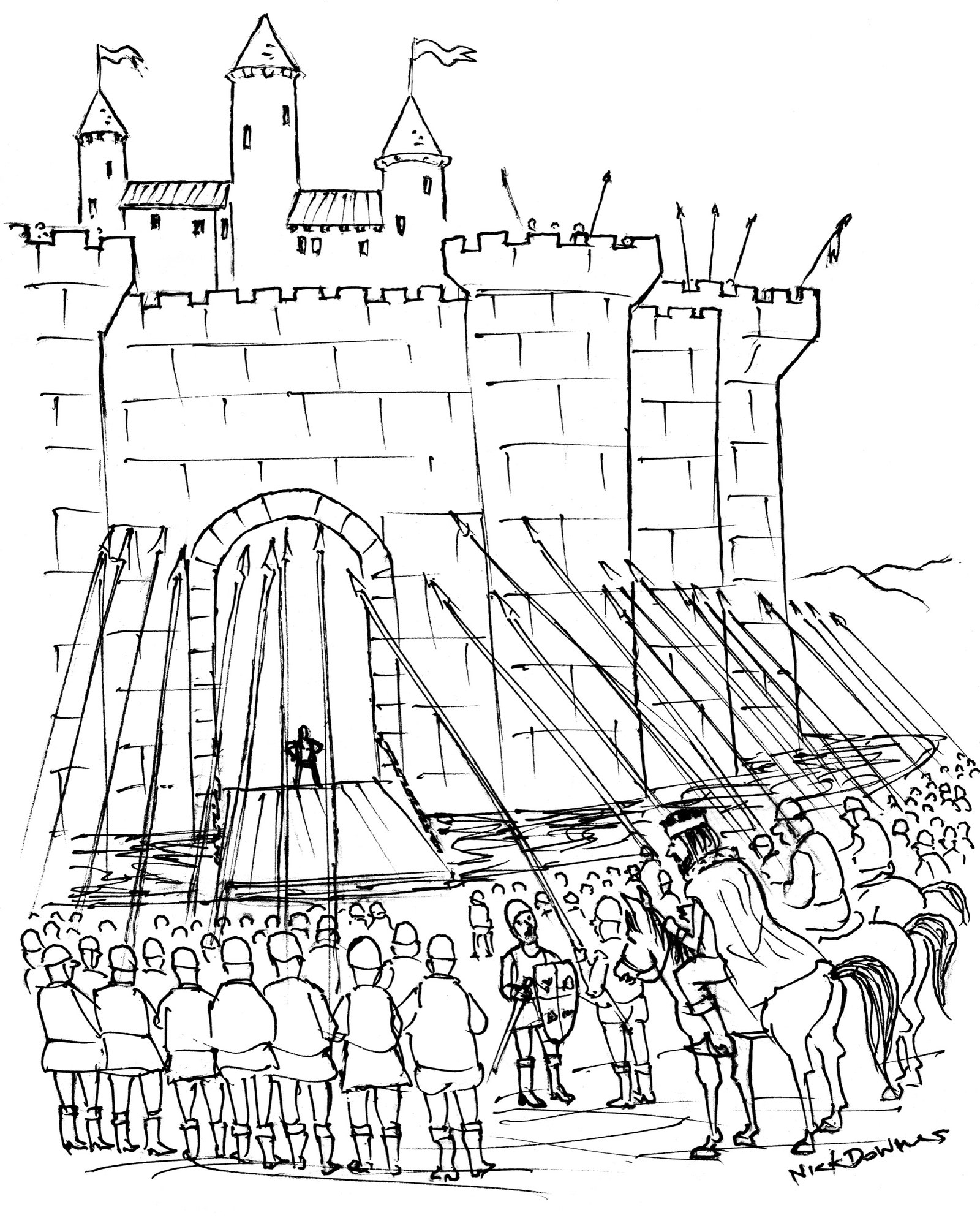

Other Catholic intellectuals—most notably the Harvard Law professor Adrian Vermeule—have voiced support for the concept of integralism, which would make Catholic teachings the basis of the state. Vermeule has written that, in his vision—which he calls “common-good constitutionalism”—“the central aim of the constitutional order is to promote good rule, not to ‘protect liberty’ as an end in itself.” He goes on, “Subjects will come to thank the ruler whose legal structures, possibly experienced at first as coercive, encourage subjects to form more authentic desires for the individual and common goods.” Vermeule has criticized Douthat for, as he sees it, naïvely hoping that liberalism and conservative Catholicism can coexist. (Moyn told me, “Ross doesn’t want to go back to the Middle Ages.”)

I asked Douthat if any part of Vermeule’s integralist vision appealed to him. “I think Vermeule is a brilliant critic of liberalism,” he said. “I don’t think the integralist vision has quite come up with a theory of why that kind of politics was defeated in the first place. As soon as the sexual revolution hit Ireland, institutional Catholicism, which had been deeply connected to state power, just completely collapsed. As soon as people were given the option to walk away, they were just, like, ‘O.K., yeah, this was sort of corrupt. We’re walking away.’ ”

Douthat did not sound nostalgic for the Irish past. But, perhaps because he’s reluctant to argue with people to his right, he tends to focus on why their ideas are unworkable, rather than on whether they are misguided. Earlier, he had told me that “religion and the institutional state being too much in bed with each other can also, ironically, cause faith to weaken, because people see it as corrupt or too involved in the gritty, everyday realities of the world.” Douthat sometimes extends this pragmatism to his critiques of the left. He said, elaborating on his earlier comment, “I think it’s important for New Yorker readers to see that this is a statement about belief systems in general, that it doesn’t just apply to Catholic Christianity. If you think of the views associated with anti-racism and wokeness and so on, there are limits to how far an élite form of progressivism can advance those ideas to the country as a whole without provoking a Ron DeSantis-type backlash. Persuasion and consensus are very important forces for religion, for politics, for ideology.”

Douthat brought up Bennet, the former Times Opinion-page editor, who resigned in June of 2020, at the height of the George Floyd protests. Bennet had run an op-ed by Senator Tom Cotton that called for sending in troops to quell riots, and many Times reporters revolted, tweeting, “Running this puts Black @nytimes staffers in danger.” The Times went on to issue a statement saying that Cotton’s op-ed “did not meet our standards.” Douthat, who worked for Bennet at both the Times and The Atlantic, told me, “Having passed through something like that has some effect on your view of liberal institutions writ large, inevitably.” For Douthat, it amplified the fear that liberalism was being overtaken by a post-liberal agenda, which would dispense with free debate in order to fulfill progressive goals.

Three years later, Douthat is less concerned. “The people who talk about passing ‘peak woke’ or whatever have a certain amount of evidence on their side,” he told me. At the Times, Bennet’s successor, Kathleen Kingsbury, has maintained a commitment to showcasing a range of political viewpoints, hiring French and the former Times Book Review editor Pamela Paul, who has emerged over the past year as a culture warrior. Perhaps because the paper does not have a columnist who will admit to voting for Donald Trump, its Opinion-page contributors have leaned into the topics—racial and sexual politics, mostly—that Douthat once worried would become taboo.

In a column about Bennet’s resignation, Douthat described the Times Opinion page as “genuinely diverse and fractious” and concluded that he hoped that vision of the marketplace of ideas would last. Douthat often speaks of the liberal institutions where he has spent his life with a certain wistfulness; paradoxically, his ultimate complaint about liberalism may be that it’s too ephemeral. “Successful religious systems, successful cultures, they’re always holding a bunch of things in tension, and dynamism and creativity come out of that kind of tension. But the tension is volatile,” he told me. “So you’re always looking for a moment of fruitful balance that is inherently evanescent and never lasts that long.”

Douthat and Tucker left their farmhouse in 2017 and moved to New Haven with their four children, who are all under thirteen. Their home, a brown-shingled Colonial on a wide, leafy street near the Yale campus, has the hectic energy that you would expect, given the average age of the residents. One afternoon, before the family dispersed to music lessons and baseball games, I chatted with Douthat and Tucker while the kids milled about. With his children, Douthat seems harried, but theatrically so, as if he enjoys playing the role of frazzled father. Even his mild attempts at discipline were undertaken with a tone of voice that suggested he was only acting the role of stern parent.

Tucker, who is the author of books on the history of house cats and the science of motherhood, first met Douthat in high school, when he and Barbaro were on an opposing debate team. (She told me that their presentation had “a lot of flair.”) They met again in college and began dating; they have now been together for more than two decades. I was curious how Catholicism fit into their family’s life. “I’m not currently Catholic,” Tucker said, with a self-conscious smile. Douthat shot me a glance, as if to preëmpt any reaction I might have. “The kids are, and I go to church,” she added.

“Abby has been incredibly gracious,” Douthat said.

Tucker comes from a long line of Irish Catholics on her mother’s side, but she attended United Church of Christ services growing up. She seemed not to mind attending Catholic Mass now, even if it clearly wasn’t quite for her. “It’s nice not to have—” She stopped herself. “I always call them the wrong things.” I wasn’t sure what she meant. “It’s nice not to have priests”—she had found the word—“come and go with a cult of personality.” As she was speaking, Douthat looked slightly embarrassed by my surprise, but I didn’t sense any tension between them, and Tucker seemed to find the whole thing funny.

Tucker, in our conversations, kept returning to Douthat as a man of seeming contrasts, with a through line of almost radical openness to new ideas and experiences. “If you tell him any idea, he’s going to be the last person to dismiss it, even if it’s a really weird idea on its face,” she told me. She expressed admiration, mixed with curiosity, about how his willingness to experiment sat side by side with his conservatism. As an example, she mentioned having sent their kids to a progressive school in New Haven, which Douthat’s sister had also attended. “The idea of fostering a creative thinker who’s constantly turning problems over in their mind—that’s the view a lot of progressive schools have,” she told me. “That’s kind of the goal.” I said I was a little surprised that this was their family’s outlook, because Douthat had written so many columns that were critical of progressive educational institutions.

She responded that, in fact, the school’s philosophy was very much congruent with how Douthat approaches life. “We’re reaching for ideas, and we’re making our ‘beautiful mistakes,’ as they call them, and we’re not constantly being bogged down by conventional thinking,” she said. “And I think that Ross defines that for me.” We began talking about the church they attended, which she characterized as being “on the conservative end of the spectrum” with “many families of large numbers of kids” and “people who get dressed up.” This sounded almost like a caricature of a conservative Catholic church, but Tucker saw it, like the school, as a place for her family. She told me, “Ross belongs in both those places.” ♦