Opinion | Why a shave and improved speech left John Fetterman’s critics so suspicious

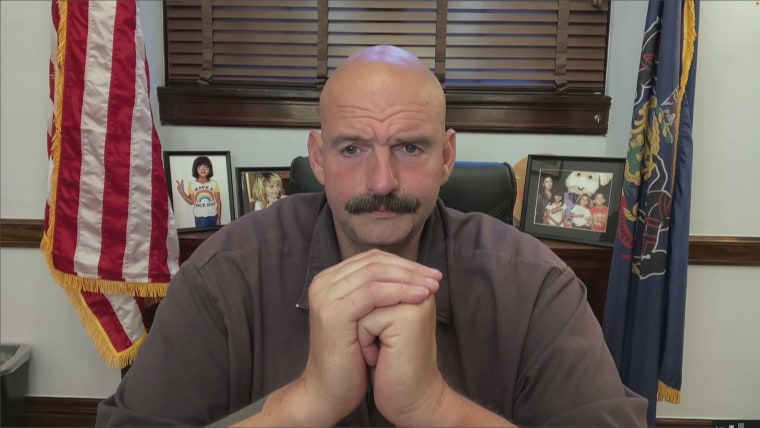

At 6 feet, 8 inches tall and about 270 pounds, Sen. John Fetterman, D-Pa., is a very large man with a style and a demeanor that’s unique among politicians. For example, his decision to dress casually in the Senate — he often wears gym gear such as hoodies and shorts — has led to some consternation among his political opponents.

Despite this uniqueness, there are some claiming that the Fetterman we see at the U.S. Capitol is a fake and that the real Fetterman is employing a body double. The conspiracy appears to be a continuation of earlier discourse about Fetterman’s speech issues following his stroke now that his speech in interviews is much improved. Fetterman also took the daring step of changing his facial hair. Even such mundane things can become a recipe for conspiracies in such a highly politicized environment.

Although people can (and often do) improve steadily after having a stroke — and changing one’s facial hair is not exactly uncommon — for these conspiracy theorists, there’s a better explanation for Fetterman’s noticeable recovery and subtle appearance changes: That it isn’t Fetterman.

The conspiracy appears to be a continuation of earlier discourse about Fetterman’s speech issues following his stroke now that his speech is much improved.

Fetterman addressed the body double rumors with a joke Wednesday, calling those rumors true. “I’m Senator Guy Incognito,” he said, referring to a Simpsons character who looks exactly like Homer. And on his campaign website, he’s selling a T-shirt with the words “John Fetterman’s Body Double.”

Why do people believe and spread conspiracies like this?

A common assertion among people who believe such stories is that they’re “critical freethinkers” and nonconformists, unlike the “sheeple” who blindly follow “official” narratives and the “lamestream media.” And, indeed, there is some research showing that conspiracy believers tend to have a strong need for uniqueness and are drawn to theories that are supported by a minority of respondents.

Interestingly, however, the empirical evidence also indicates that conspiracy believers tend not to be very strong critical thinkers after all. Instead, research shows that conspiracy theories flourish primarily among people who tend to strongly rely on their intuitions and gut feelings and — consequently — do not engage in much analytical or reflective thought. In fact, one of the stronger predictors of conspiracy belief is lack of commitment to the idea that beliefs ought to change according to evidence. Rather, conspiracists tend to hold that some beliefs are too important or even sacred to truly question.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, those same tendencies are central to understanding why some people fall for fake news and other types of misinformation. Other beliefs, such as in the paranormal and anti-science beliefs are apparently driven (to some extent) by this lack of reflective thinking. Despite an identification with the “critical freethinker” label, it turns out that many believe conspiracy theories not because there is good evidence for them, but because they feel intuitively right. If the rumor were properly scrutinized, one might consider how difficult it would be for Fetterman to find a suitable body double and conclude that there are more likely explanations for why he appears to be healthier.

The empirical evidence indicates that conspiracy believers tend not to be very strong critical thinkers after all.

But a central question remains: What stops people from questioning whether their beliefs are wrong?

New research out of my psychology research lab at Cornell University suggests that it’s not just that people aren’t willing to make the effort to think analytically, but that they aren’t aware that they even need to think analytically. In particular, in work that is not yet peer reviewed, we found that conspiracy believers are particularly prone to overestimating how good they are at (even basic) cognitive tasks. For example, we gave participants a perception test that is exceptionally difficult. They were asked if a chimpanzee or a baseball player is occluded in a particular image.

How one answer this problem isn’t really important (it isn’t indicative of any particular skill). The important question is how well one thinks one did on the test. People who report doing better are more likely to be conspiracists even though conspiracists are no better on the test than anyone else.

What this suggests is that conspiracy believers have an inflated view of their cognitive abilities. That is, they are not just overconfident about their beliefs, but about their brain power. This may block them from even considering whether their beliefs are false.

Consistent with this — and in contrast to previous work showing that conspiracy believers have a strong need for uniqueness — we also found that conspiracy believers massively overestimate how much others agree with them. For example, we asked a group of participants if they believed the Sandy Hook false flag conspiracy popularized by Alex Jones. Only 8% of the people in our study said they believed it. However, that 8% estimated that 61% of others agreed with them. Despite being in a tiny minority, they thought they were in the majority!

We also found that conspiracy believers massively overestimate how much others agree with them.

Despite conspiracy believers’ longing to feel unique, they largely believe that most people agree with even the extremely uncommon and “fringe” beliefs they hold. This is, at least partially, a consequence of overconfidence: The possibility that their beliefs are wrong is so remote that it’s hard for them to imagine others disagreeing.

The John Fetterman body-double conspiracy is a great example of this. The claim is so outlandish that it could easily be confused with satire. Yet, it is likely that some genuinely believe it. And they probably think that many others believe it as well.

There is also a deep irony here. Those who label themselves as “critical freethinkers” are not only less analytic, but more overconfident. It is little wonder how conspiracies — such as the Fetterman body-double conspiracy — flourish and build up such a resistance to correction.