Escape from the rabbit hole: the conspiracy theorist who abandoned his dangerous beliefs

Brent Lee struggles to explain why he used to believe that a cabal of evil satanic paedophiles was working to establish a new world order. He pauses, looks sheepish, and says: “I cringe at all this now.”

For 15 years, Lee collected signs that so-called Illuminati overlords were controlling global events. He convinced himself that secret societies were running politics, banks, religious institutions and the entertainment industry, and that most terrorist attacks were actually government-organised ritual sacrifices.

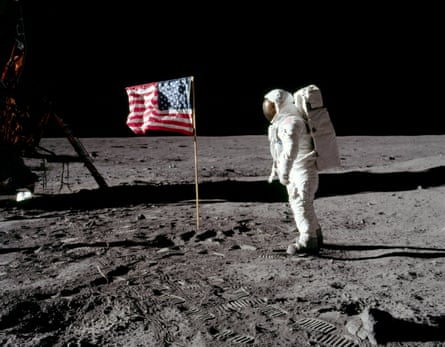

He was also inclined to believe in UFOs, and that Stanley Kubrick staged and directed the filming of the moon landing. He saw satanic symbols in the London 2012 Olympics opening ceremony and spent most of his time discussing these theories with an online community of fellow believers. But in 2018 something shifted, and he began to find the new wave of conspiracy theories increasingly implausible. “I was sick of it. I felt, I can’t deal with hearing this any more because it’s no longer what I believe, so I just logged off the internet,” he says.

Now Lee is trying to help other conspiracy theorists to question their worldview. He will address a conference in Poland on disinformation in October, and has launched a podcast unpicking why he held these beliefs so fervently and why he was so deluded.

Amiable and articulate, Lee is disarmingly willing to admit that he got things spectacularly wrong, but it is still challenging to have a conversation with him about his abandoned belief system. Most of the theories seem so preposterous that the process of trying to understand them becomes exhausting. When I strain to follow the logic, he says: “Don’t try to get me to make it make sense because it doesn’t. This is why I get so embarrassed about what I believed. You just buy into this ideology and think that’s the way the world works.”

His reasons for abandoning the “truther” movement (truthers believe official accounts of big events are designed to conceal the truth from the public) are also hard to slot into a conventional worldview. Lee veers between feeling ashamed and amused by his own convictions while also pointing out that it would be a mistake to dismiss these ideas with an impatient eye roll, because they are very dangerous.

Versions of the same ideas have gained greater currency in the years since he stepped away from them. In the US, the influence of QAnon has shifted from the fringes to the mainstream, and social media has been flooded with the group’s misinformation. A 2020 Ipsos poll found that 17% of Americans believed that “a group of Satan-worshipping elites who run a child sex ring are trying to control our politics and media”.

In 2003, Lee was 24, a musician working behind the till in a garage in Peterborough, when he downloaded a series of videos from the internet that offered alternative perspectives on 9/11 and suggested the terrorist attack on the Twin Towers in New York in September 2001 was self-inflicted by the US government, as a way of justifying military action in Afghanistan and Iraq. His starting point was a strong anti-war stance and a healthy scepticism about politicians’ motivations, but from there he came to believe that a network of secret societies and cults was running the world.

It is hard to summarise precisely why he made that step – and harder still to fathom his later preoccupation with paedophiles and ritual murders. He attempts to explain when we meet on a weekday afternoon in an empty Bristol wine bar (idle waiters keep glancing over, startled by fragments of conversations about satanic lizards), but I have to email him a few days later to ask him to try to explain again.

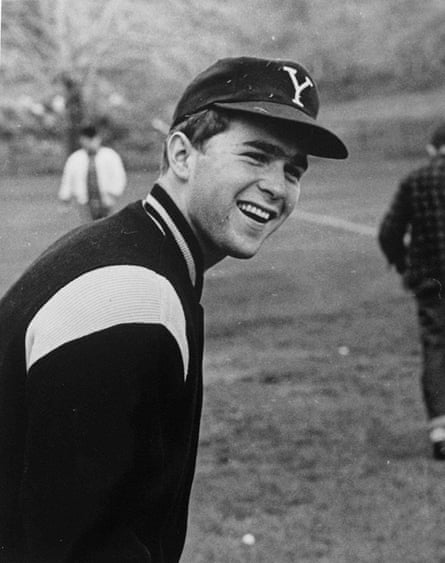

His answer remains confusing, but begins with George W Bush and Democrat John Kerry’s membership, when at Yale University, of the Skull and Bones club, a secretive student society that conducts bizarrely morbid rituals. This led him to believe that there were evil politicians interested in satanic rituals. “Once you’ve been swayed by these arguments, it’s easy to just keep going down the rabbit hole, finding more dots to connect,” he says. “Once you have such a skewed view of the world, you can be convinced of other stuff.”

The tone of his podcast is disconcertingly upbeat, chatty and jokey with other ex-truthers who join as guests. “If I’m laughing at conspiracy theorists, it’s because I’m laughing at myself,” he says. “It is funny – that you’re adults who believe in Santa Claus or something equally ridiculous.”

It feels peculiar to be jolly about something that soaked up his life for so many years so devastatingly – to the exclusion of forging a career or starting a family. It also seems a glib response to an environment that has a powerful streak of antisemitism and white supremacy running through it. Lee says he only fully understood the antisemitism when he stepped away.

What made him vulnerable? Partly, he blames his education. “I wasn’t taught how to assess information or how to do research,” he says. “I don’t think I lacked intelligence but I was very naive about politics and how the world actually works.”

He had a disrupted education: first, at a US high school on the Frankfurt military base where he spent much of his childhood with his English mother and American stepfather, who was serving in the US air force; later, at a college in England, from which he was expelled (for smoking weed) and started playing in a band. He spent hours on music production on his computer and developed sophisticated internet skills, at a time when most people were barely online. This gave him early access to sites run by conspiracy theorists such as David Icke; soon he was spending nine hours at a stretch consuming truther content online.

His friends, family and fellow band members were bored by his obsessions and he gradually withdrew to focus on online friendships with people who were also ready to believe that the Illuminati and Freemasons had infiltrated global governments.

When the 7/7 attacks took place in London in 2005, killing 52 people, Lee was online, searching with fellow truthers for evidence that the terror attack was orchestrated by the UK government. They examined footage of the attackers going to the train station in Luton and were made suspicious by the way railings appeared to slice through the leg of one of the attackers; they decided the image had been Photoshopped before being released by the police. Now he acknowledges that the glitches might simply have been the result of shaky CCTV technology rather than the work of cultist masterminds.

He spent months building an alternative explanation for the attacks and disseminating his theories through his blog. “I’m ashamed of putting so many lies out there. I didn’t mean to lie, I just had the wrong picture.” He maintains this came from a good place. “I wanted to find the real people who had organised the attacks; I wanted justice for the victims. But I was wrong and it took away guilt from the real perpetrators, people who did something atrocious.”

Naomi Klein examines the mushrooming of conspiracism in her new book Doppelganger, noting that people often come under its sway because they are searching for a practical solution to a sense of unfairness. Conspiracists have a “fantasy of justice”, hoping that the evil-doing elites can be arrested and stopped. “Conspiracy theorists get the facts wrong but often get the feelings right,” she writes. “The feeling that every human misery is someone else’s profit … the feeling that important truths are being hidden.” She quotes digital journalism scholar Marcus Gilroy-Ware’s conclusion that: “Conspiracy theories are a misfiring of a healthy and justifiable political instinct: suspicion.”

Lee’s appetite for conspiracies started to wane when the “alt-right” US broadcaster Alex Jones began claiming that the 2012 Sandy Hook school shooting was a hoax, that no one died and the parents of the 20 children who died were “crisis actors” – hired to play disaster victims. Lee found this implausible and felt irritated by other wild theories swirling around the internet – that Justin Bieber and Eminem were Illuminati clones, that a paedophile ring, involving people at the highest level of the Democratic party, was operating out of a Washington pizza restaurant. “I looked at Pizzagate and thought, ‘Well that’s just stupid.’” (He spends six podcast episodes debunking the Pizzagate conspiracy; this seems a pithier summary.)

When Covid triggered a popularity surge for conspiracy theorists, Lee was already done with it, and simply noted that if there really was a global movement working to establish a new world order through the pandemic, they were going about it in a strikingly ill-coordinated and muddled manner. “The governments weren’t acting in lockstep with each other. There was no well-oiled machine; it was disorganised. No one was in charge.”

He understands why other people were attracted to the idea: “Just like 9/11 brought people into conspiracies, Covid was another moment when people were scared and wanted answers, and they found conspiracy influencers saying: ‘Don’t worry about it, it’s not real.’”

Lee was an early adopter of ideas that have surged in popularity as people spend more time online, and as trust in the mainstream media falters with the suggestion (much propagated by the former US president Donald Trump) that they are spreaders of fake news. The emergence of QAnon (which propagates the baseless theory that Trump was battling a cabal of sex-trafficking satanists, some of whom were Democrats) has attracted more people to this world. Lee’s interests preceded the arrival of powerful opinion-shaping algorithms pushing people into closed loops of fact-free narratives. Since leaving the fold he has developed a sharp clarity about the self-interested financial motivations of conspiracists who work to monetise their online presence with increasingly wild, clickbaity dispatches.

“It’s a big problem that’s getting much worse. People are being manipulated with misinformation,” he says. He was disturbed by the death in 2021 of Ashli Babbitt, the woman shot by a police officer during the 6 January riots inside the US Capitol. Her Twitter feed was full of references to QAnon conspiracies. “That could have been me or my partner,” he says of Babbitt. “She believed what we believed. That’s what made me think I should speak out, tell my story to help bring other conspiracists out, so they don’t become the next Ashli.”

Lee now has a factory job (he has been asked by his employers not to mention the company name) but spends every lunch break and evening analysing new waves of misinformation. The process of detoxing has sucked him further into the world he rejected. “I want to combat them and challenge them. I am totally obsessed with explaining what they are.”

Alexandre Alaphilippe, executive director of EU DisinfoLab, a Brussels-based NGO, has invited Lee to speak to academics and regulators at a conference on tackling the spread of online misinformation. “Policy researchers sometimes forget the real impact on human lives. We’re no longer talking about minor fringe movements; radicalisation is spreading through a complex system of beliefs. It’s not something that should be taken lightly,” he says.

Callum Hood, head of research at the Center for Countering Digital Hate, says that social media platforms have boosted engagement with extreme ideas. “Conspiracies can appear ridiculous to non-believers, whether it’s David Icke’s claims about a reptilian takeover or QAnon claims about a global cabal of paedophiles. But what makes this dangerous is that someone can start by sympathising with David Icke’s attacks on ‘the establishment’ and end up buying into his grotesque conspiracies about the Holocaust,” he says.

As a former conspiracist, Lee hopes he will be better equipped to help people still caught up in these beliefs. Rather than antagonising them, he is able to take a more empathetic approach. “These ideas aren’t alien to me – they are second nature. Most conspiracists want a better world. They think something bad has happened, and they want to expose it. I think if you can lean into that with them, and say: ‘Yes, I understand why that would worry you, but perhaps it’s not actually what’s happening.’ I think that’s a better way to approach it.”

He says it takes time and energy to help people dismantle the many layers of complex theories. Concerned about the implications for free speech, he is not certain that greater online regulation is part of the answer. “I usually tell friends and family members: ‘You are the best person to do it. They will trust and respect you more than any stranger who challenges them, so you are going to have to familiarise yourself with their beliefs. You also know how far you can push them before they get annoyed, don’t cross that line. Keep them close, be respectful and remind them that you value their concerns’.”

So far, Lee’s attempts to save others have had limited success. He has been ostracised by his former online community. “My first intention was just to bring my friends back out of the rabbit hole – that backfired on me. They have completely cut me off, treated me like a pariah.” Some have suggested that he has been paid off by “the elites”, but he is determined to persist. “There are friends and family of people caught up in this who contact me to say: ‘Thank you for sharing this: you really believed in all this craziness, you were super deep but you came out – and this gives us hope.’”

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from The Guardian can be found here.