Was It Smarter to Accept or to Reject the COVID Vaccines?

What a Swedish study found to be “smart” may reflect pressures for social acceptability rather than intelligence, per se.

Health Viewpoints

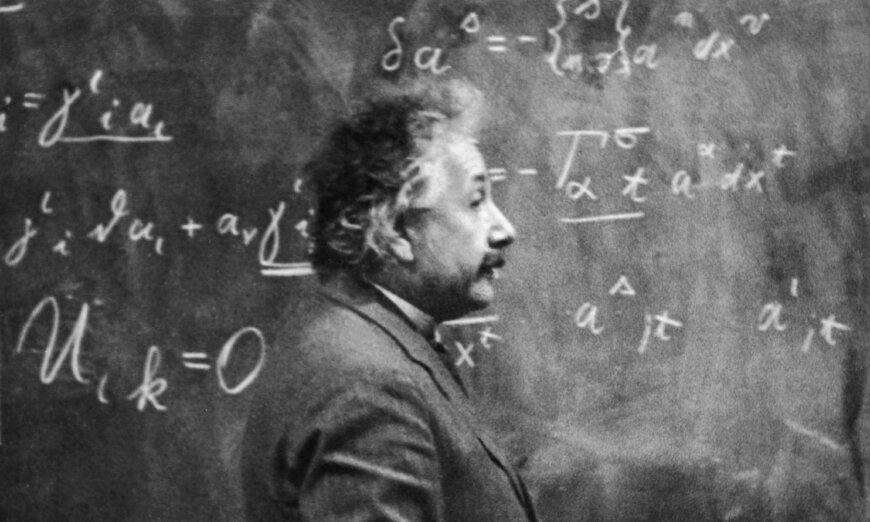

Study authors Elinder et al. considered 750,000 Swedish men aged 42 to 59 who had served in the military in youth and nearly 3,000 women who had enlisted. The authors examined the veterans’ scores on intelligence tests given at about age 18. Those scoring highest in the past had a COVID-vaccination rate of 80 percent at a mean of 50 days after COVID vaccine availability, whereas those in the lowest scoring group arrived at the 80 percent rate at 180 days, as the authors show here:

Then we have the surprising finding that those who scored highest on an intelligence test were the earliest to jump on board with the novel medical procedure.

Mr. Berenson asserts that moderately smart people took the COVID vaccines but that the extremely smart—with IQs higher than 130—did not.

Eugyppius argues essentially that the ultra-intelligent knew better than to take the COVID vaccines but tend not to have as much public influence as the next tier down of test takers. This is presumably due to the unpersuasive nature of their esoteric ideas and language, and their very small numbers, getting drowned out in public forums, etc., and that “midwits” carry the day and establish policy due to their greater numbers, persuasive abilities, and influence.

There is a problem with the correlation that neither Eugyppius nor Mr. Berenson picked up on, although Eugyppius alluded to it and then mostly dismissed it. That is, test-taking and success at test-taking are not entirely a measure of discerning truth because test writers are fallible humans. Therefore, the successful test-taker can be someone who more cleverly discerns, whether from test-taking experience or social intelligence, what it is that the test writer is looking for, what that author or teacher wants to hear, and the type of conformity that the test writer is seeking—and is seeking to reward—in the test-taker.

Choose the best answer. Vaccines are:

a) Important to pediatricians’ work with sick children.

b) Irrelevant to human diseases.

c) The greatest life-saving health intervention in history.

d) Developed and produced for profit.

The “smart” test-taker will choose c) in order to please the test writer, whether believing it or not, and perhaps even knowing that human life expectancy greatly extended after adopting indoor plumbing and sanitation of water systems, but not closely following widespread use of specific vaccines. The other answers, a), b), and d), give off a whiff—to the experienced test-taker—of not what the test writer is probably hoping to see.

What would we find if we looked at an expectation index, where those who score high on cognitive tests at age 18 may be expected to pursue greater conformity to commonly expected norms than those who do not face such rigid demands? The former will feel the effects of more and more intense expectations of lifetime performance. This, I think, confounds the problem of assessing behavior three decades after a cognitive test.

But in which direction was cause and effect? Did a drive for conformity motivate Swedish adolescents of decades ago to pay attention, study, and conform to expectations that might at some point be reflected on a standardized test, carrying those same qualities later into adulthood? Or does the successful test-taker have the smarts to notice which way the wind is blowing, and to fall in line with, and want to fall in line with, and learn to care strongly about, social norms, to not be the dreaded social outcast? Who receives greater pressure to do this: the physician or the plumber?

Both of those types of conformity were urged to a fever pitch during the COVID era, in both carrot and stick, respectively. That is, “Get the vaccine to show your love for others,” and “Get the vaccine or else risk losing your job and other important things.” Schwartz had shown in a 1992 text, “Advances in Experimental Social Psychology,” that conformity suppresses impulses that are likely to violate norms or social expectations or to upset or harm others.

Weren’t those the very same horrors of the COVID era? Don’t violate norms or social expectations. Don’t upset or harm others. Remember Grandma, for heaven’s sake.

The Swedish study authors looked at confounding factors, but they missed the conformity or social acceptability drive among those considered or known to be intelligent, which is admittedly hard to quantify. The confounding factors Elinder et al. examined were far more concrete: marital status, parenthood, education, income, and locale, as well as a comparison of twin pairs. Of those criteria, education made the biggest difference, reducing the relationship between cognitive ability and vaccination by 30 percent.

I think critics have missed the major problem with the Elinder study. Although measuring it is nearly impossible, if we examine the drive for conformity to rules and social expectations, then the Swedish results make more sense.