Election offices face conspiracy theories, understaffing

Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

WILKES-BARRE, Pa. — The polls had just opened for last year’s midterms in Pennsylvania when the phones began ringing at the election office in Luzerne County.

Polling places were running low on paper to print ballots. Volunteers were frustrated, and voters were getting agitated.

Emily Cook, the office’s interim deputy director who had been in her position for just two months, rushed to the department’s warehouse. She found stacks of paper, but it was the wrong kind — ordered long ago and too thick to meet the requirements for the county’s voting equipment.

Conspiracy theories swiftly began to spread: Republican polling places were being targeted; Democrats overseeing elections were trying to disenfranchise Republicans.

“The feeling early on in the day was panic — concern — which grew to overwhelming panic,” said Cook, a 26-year-old native of Luzerne County. “And then at some point throughout the day, there was definitely a feeling of people are starting to point fingers — before the day was over, before things were even investigated.”

The paper shortage, corrected later in the day, turned out to be an administrative oversight by a new staff but has had consequences that are still rippling through the county of 200,000 voters, sowing doubt about how elections are run and leading to a congressional hearing.

It also serves as a cautionary tale about the perils of a change that has been largely hidden from public view but has transformed the election landscape across the U.S. since the 2020 presidential election: an exodus of local election directors and their staff.

People growing weary of dealing with the constant criticism, the unending workload, … and then finding themselves constantly in the spotlight and under scrutiny has, I think, put us in a national crisis.

– Jennifer Morrell, former local election official in Utah and Colorado

Election offices have been understaffed for years. But 2020 was a tipping point, with all the pandemic-related challenges before the presidential vote and the hostility afterward driven by false claims of a stolen election.

A wave of retirements and resignations has followed, creating a vacuum of institutional knowledge across the country. Experts in the field say widespread inexperience creates risk in an environment where the slightest mistake related to voting or ballot counting can be twisted by conspiracy theorists into a nefarious plot to subvert the vote.

“People growing weary of dealing with the constant criticism, the unending workload, the inability to have any sort of work-life balance at all, and then finding themselves constantly in the spotlight and under scrutiny has, I think, put us in a national crisis,” said Jennifer Morrell, a former local election official in Utah and Colorado. “This feels like a really precarious spot.”

‘Papergate’

The dangers are not lost on Al Schmidt, a Republican who helped oversee elections in Philadelphia and faced death threats in 2020. Now Pennsylvania’s top election official, Schmidt said his department has been working to increase training materials and build relationships among local election officials in the hopes of reducing future mistakes.

“There are no redo’s of Election Day,” Schmidt said. “Everything has to be right, and it has to be right every time.”

That has not been the case in recent years in Luzerne County. The 2022 ballot debacle, referred to locally as “Papergate,” was just the latest problem in a county that is on its fifth election director in the three years since the 2020 presidential election.

The troubles have only increased doubts among voters, some of whom were already distrustful of elections because of the persistent falsehoods about the last presidential contest — despite Republicans holding 10 of 11 seats on the local governing board.

“We’ve had a whole host of things that have gone on in this county where people sit back now, the electorate sits back and goes, ‘They’re just rigging the election,'” said County Controller Walter Griffith Jr., a Republican and longtime resident. “I try to tell people we got to figure out a way to get past all of those things because you’re not going to win anything and you’re not going to make anything better by doing that.”

‘So much divisiveness’

There’s no one reason why the county has experienced so much turnover in its election office, but there is little doubt the churn has added to problems confronting the department. Staffers reported finding instructions about important election procedures written on scraps of paper.

Griffith and others note recent hires have lacked significant election experience.

“They’re brought in because a lot of people don’t want to work in elections, and that’s understandable with so much divisiveness,” said Denise Williams, a Democrat who chairs the Board of Elections, a citizen group formed under the county charter that, among other duties, certifies election results.

There are no redo’s of Election Day. Everything has to be right, and it has to be right every time.

– Al Schmidt, Pennsylvania election official

‘We have nothing to hide’

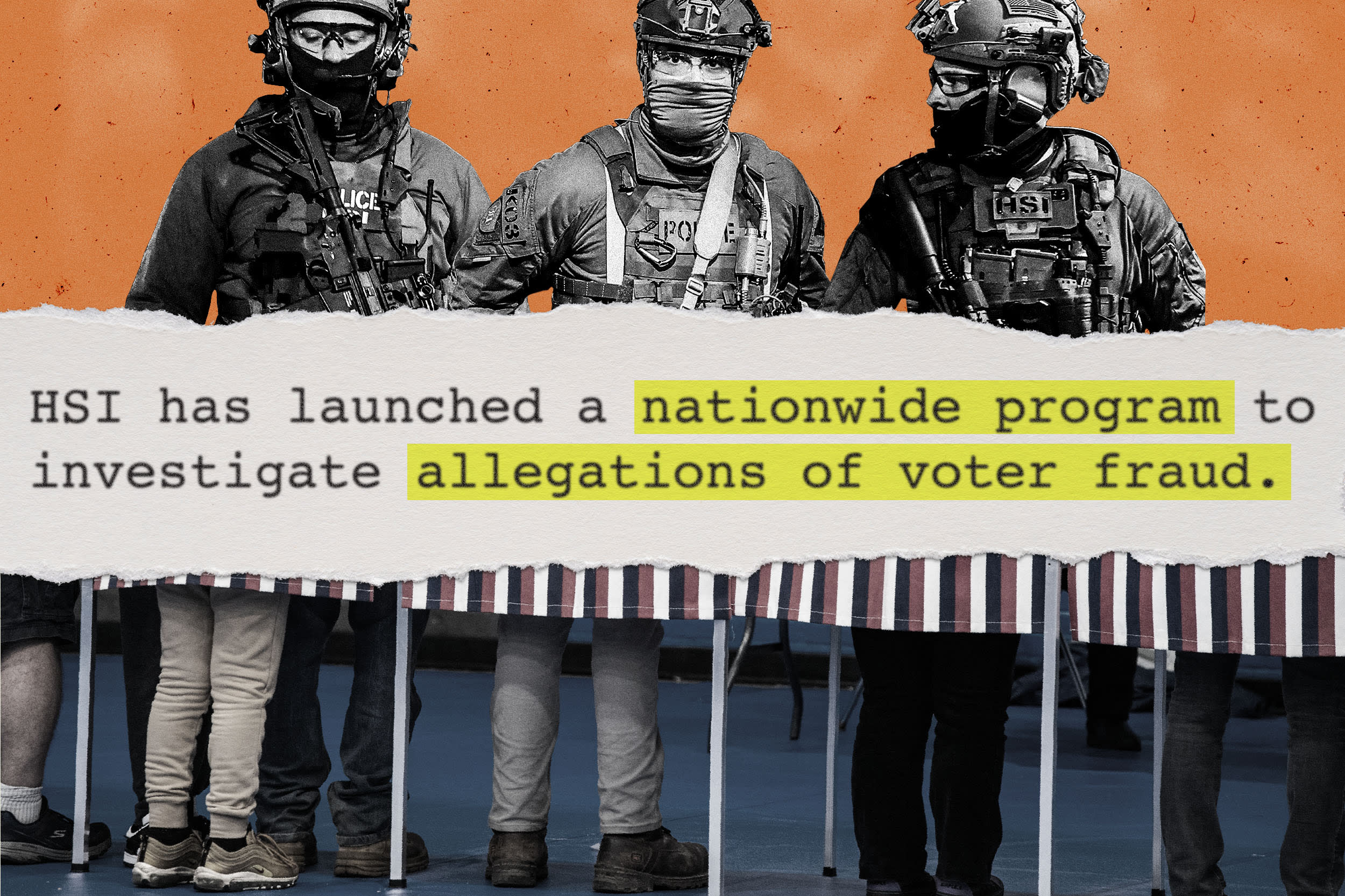

Nationally, the harassment of election workers has drawn the attention of Congress, state lawmakers and law enforcement. During a 2021 congressional hearing, Schmidt quoted one of the threats he had received: “Tell the truth or your three kids will be fatally shot.” Lawmakers in several states have increased criminal penalties for those who threaten election workers, and the Justice Department has formed a task force that has charged more than a dozen people across the country.

U.S. Rep. Bryan Steil, a Republican from Illinois who chairs the committee that held the hearing, said it provided important answers and accountability for local residents.

A new county manager, Romilda Crocamo, was hired earlier this year. She brought in a consultant to create an elections manual so there will be no confusion about what needs to be done if an employee leaves.

She also has been encouraging staff to be more accessible, hold public demonstrations showing how they work and provide regular updates on election preparations, including how they handle unexpected problems — like a recent glitch that mixed up city council races on some ballots.

“When you don’t do that, then the stories start morphing into something that really isn’t happening,” Crocamo said. “We have nothing to hide.”