Lee Harvey Oswald Had Two Weapons With Him That Day. Each One Told a Story.

Americans fell hard for conspiracy theories in the postwar era. That was, in part, because their own government repeatedly conspired against them, from COINTELPRO spying on Civil Rights and antiwar activists to government doctors denying treatment for syphilis to unwitting Black Americans during the Tuskegee experiments. But sometimes Americans fell for conspiracy theories because those theories offered mystery and uncertainty when the simple truth belied the world’s seeming complexity. Take the discovery that a disgruntled 24-year-old Communist sympathizer named Lee Harvey Oswald, trained in marksmanship by the United States Marines, could so easily buy a weapon of war and use it to murder a president.

As no less than FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, a man who knew a thing or two about conspiracies, remarked to Lyndon Johnson the day after the assassination, as Oswald sat in a Dallas jail cell, and as Hoover’s agents scoured the country in search of intelligence about the assassin: “It seems almost impossible to think that for $21 you could kill the president of the United States.”

In an era when the threat of nuclear annihilation hung over world politics, how could a cheap rifle, which one infamous gun dealer described as a “throwaway gun,” kill the world’s most powerful man? Just about anybody of age and with proper identification could walk into one of thousands of gun stores across the country—anybody could walk into Sears!—and buy the same or a similar gun for as little as $10. Or anyone could, like Oswald, scribble a name and information on a mail-order coupon and have it delivered to a P.O. box a few weeks later.

<section data-uri="slate.com/_components/product/instances/clp8sowgd0033356yjxucwwgw@published" class="product " data-product-name="Gun Country: Gun Capitalism, Culture, and Control in Cold War America” data-product-price=”$22.95″>

<a href="http://www.amazon.com/dp/1469677245/?tag=slatmaga-20" class="product__name" data-product-name="Gun Country: Gun Capitalism, Culture, and Control in Cold War America” data-product-price=”$22.95″>

Gun Country: Gun Capitalism, Culture, and Control in Cold War America

By Andrew C. McKevitt. University of North Carolina Press.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page.

Thank you for your support.

Since the end of the Second World War, millions of Americans had bought guns just as Oswald had, with the exception that they had no intention of assassinating a head of state and therefore rarely took pains to hide their identities. Oswald ordered two firearms through the mail, using the pseudonym “A. Hidell.” One was a Mannlicher-Carcano rifle he used to kill Kennedy, and the other was a Smith & Wesson revolver he used to murder Dallas police officer J.D. Tippit hours later. Oswald may have broken the law when he lied about his identity, as did many buyers with felony convictions, or even some children, who purchased guns through mail-order. But millions of other Americans who bought guns in a similar fashion did so perfectly legally.

The seemingly impossible became plausible thanks to the golden age of the American gun owner.

Both of Oswald’s guns had a story to tell apart from their role in the tragedy of Nov. 22, 1963. Their story is the story of America’s postwar gun crisis and the mass accumulation of cheap guns with few restrictions, the effects of which we still live with today.

The first weapon pointed to the abundance of guns within Americans’ reach thanks to their victory in the Second World War. As deputies Eugene Boone and Seymour Weitzman emerged onto the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository Building from which Oswald fired three shots at the president on Nov. 22, 1963, they saw the weapon tucked into the corner. Weitzman thought he knew it on sight: It was a Mauser, he reported, a bolt-action rifle originally designed in Germany in the late 19th century and then replicated and churned out by the millions in more than a dozen countries.

Weitzman had made a perfectly reasonable mistake—he spied not a Mauser but a Mannlicher-Carcano, a rifle of Italian provenance with a similar profile and function. Like the AR-15, the Mauser birthed plenty of knockoffs, and the Carcano was among them. But because of that initial mistake, the gun question quickly became a conspiracy theory within a conspiracy theory. Dallas police initially repeated Weitzman’s claim of seeing a Mauser but later issued a correction, which became ripe fruit for conspiracists convinced the true killers were trying to hide the real assassination weapon.

There was no conspiracy here, however. At the time, Mausers were easily identified and possibly misidentified, much as someone today might identify as an AR-15 any number of dozens of “black rifles” with similar profiles and functions. Mausers were common battlefield rifles in the first half of the 20th century. But Europe’s continental wars came to an end in 1945, and as new rifle designs replaced old, they became obsolete, sitting in storage caches scattered across the continent and the world.

As a result, it was also not uncommon to see a Mauser or a Carcano in the postwar United States. In fact, they were among the most bought and sold firearms in the quarter century following the end of the Second World War, thanks to a cohort of gunrunners who sought to connect global gun supply with American demand.

In the early 1950s, a cohort of ambitious young gun capitalists in the United States saw opportunity in Europe’s war trash. Led by a brash, boyish firearms aficionado and entrepreneur named Samuel Cummings, they went dumpster-diving across the continent, hoarding millions of firearms that had sat collecting dust. Back home, American consumers were eager to cash in their peace dividend, now flush with expendable income and leisure time in the afterglow of wartime triumph.

Cummings’ pitch to the American people was that because they had won the war, they deserved the war’s guns. His advertisements, packed with as many different guns from around the world as he could fit on the page, said as much. By the end of the decade, Cummings was annually importing hundreds of thousands of war surplus weapons, Mausers and Carcanos chief among them, for sale on the U.S. consumer market.

The flood of “weapons of war” from Europe did not go unnoticed. U.S. gunmakers saw the trend as quickly as anyone. It was hard to walk into a gun store and see, on the one hand, a $150 American-made Winchester hunting rifle and, on the other, a $10 Carcano, and not ask some questions about the discrepancy.

The manufacturers, located primarily in the “Gun Valley” of Massachusetts and Connecticut, lobbied their congressional delegations. In 1958, Connecticut Rep. Albert Morano and Massachusetts Sen. John F. Kennedy submitted a bill that would have strangled Sam Cummings’ budding firearms empire in the cradle. The gunmakers claimed that Cummings’ $10 rifles—and his weren’t the only ones, but nobody sold more than he did—would put the U.S. industry out of business if left unchecked. That was an outcome that the U.S. government itself couldn’t afford. If the Soviets came charging through the Fulda Gap, who would make the firearms U.S. soldiers would carry into battle? The survival of the U.S. firearms manufacturers was a matter of national security.

Cummings rebuffed the U.S. gunmakers’ claims and offered a counterargument rooted in consumerism rather than military preparedness. He and the traditional manufacturers weren’t even in competition, he said. After all, who goes shopping for a high-quality, brand-new $150 hunting rifle and goes home with a beat-up $10 war surplus weapon? It would be like going to the car lot looking for a new Cadillac and going home with a busted-up 20-year-old Buick. Indeed, Cummings argued, he was good for the industry, expanding its consumer base and roping in millions of new gun owners, and in turn, good for America.

Cummings also had an unexpected ally: the U.S. Department of State. Congress asked the agency to explain some of the more unsettling data it had seen on individual shipments of tens of thousands of weapons of war coming into the United States. They also wanted to know if guns that the United States sent abroad as Cold War foreign assistance were coming back to be sold to American consumers. The State Department ostensibly issued a license for every single imported gun. What was the official U.S. position on all this small-arms traffic?

State officials testified before Congress and explained that, for one, there was little evidence that imported guns were of recent vintage. Almost all of them were weapons from the Second World War. Military allies around the world were upgrading their arsenals in the 1950s; when the United States sent new firearms abroad, it was possible that old stockpiles would make their way onto the American consumer market, the largest and most open of its kind in the world.

Further, State officials wanted to clarify that the government’s policy of approving hundreds of thousands of firearms imports entering the country and flooding the consumer market each year was, in fact, good for America. “I am frank to say that when there are questions of surplus arms cropping up abroad,” one State Department official explained to Congress, “it may very often be the better part of valor and indeed the best part of our foreign relations to have them imported into this country rather than float around.”

Especially in the emerging “Third World,” where Europe’s imperial powers left vacuums of instability in their former colonies, just a few thousand military firearms in the hands of a disciplined insurgency could determine the fate of a nation. “It may be darned important that we have some ability to have those arms come here, rather than go somewhere else,” the State Department official concluded. In other words, what was good for Sam Cummings was good for America.

One of the war surplus weapons that entered the United States by the millions in the decade before the Gun Control Act of 1968 would prohibit the practice was Oswald’s Carcano. But—thankfully, Cummings joked, in his trademark sardonic style—it wasn’t one of his guns. When Congress had come knocking with questions about imports back in 1958, Cummings claimed to be the only U.S. importer of Carcanos. He sold them for as little as $9.95 through the mail, joking that a Carcano was a “throwaway gun” you could leave out in the woods when you bagged your first deer. His tongue-in-cheek advertising copy described it in his characteristic foreign-language gibberish as a “supre, supremi, Italio supremo if there ever was one.”

But nobody was more attuned to the cheap gun market than Cummings, and he started to see the market shift after 1958. Plenty of Carcanos, perhaps millions, still sat in warehouses and depots in Italy, but Cummings was confident that he had already inspected and scooped up every one worth selling on the American market. He wasn’t interested in getting stuck in a Carcano bubble.

His competitors, always years behind Cummings, didn’t see the bubble. They only saw the tremendous profits to be made from buying cheap war-surplus rifles in Europe and pitching them to the American consumer. One also-ran was Vanderbilt Tire and Rubber Corporation of New York City. In 1960, Vanderbilt established Crescent Firearms as a subsidiary specializing in imported war-surplus weapons. In its eagerness and naïveté, as Cummings told the story, Crescent paid $1.12 each for more than half a million Carcanos still sitting in Italy, guns Cummings had inspected and rejected—if they were worth buying, they’d already be in one of his warehouses.

Wikimedia Commons

Because Crescent was so new to the game, it lacked Cummings’ efficient logistics network for cleaning, “sporterizing” (that is, preparing a battered weapon of war for use as a sporting firearm), and transporting war surplus rifles, and as a result overpaid to get the guns to New York. Cummings traded in information about the global gun market as much as guns themselves; knowing that so many Carcanos were about to flood the U.S. consumer market, he slashed retail prices on his own stock both to undercut Crescent and to get out of the Carcano game before the junk flooded it.

Crescent spent years trying to offload its overpriced Carcanos. In February 1963, the company shipped an order to Chicago’s Klein’s Sporting Goods, a mail-order retailer that offered a cornucopia of global guns in its magazine ads. On March 13, 1963, Klein’s received a coupon clipped from an ad it ran in February’s American Rifleman, the magazine sent to all members of the National Rifle Association. Included with the coupon was a money order for $21.45, intended to cover the $19.95 cost of a Mannlicher-Carcano, specially outfitted by Klein’s with a 4x telescopic sight, and shipping and handling. One week later Klein’s shipped the rifle to A. Hidell, P.O. Box 2915, Dallas, Texas. And just eight months after that, that very Carcano, one of millions of war surplus guns unloaded on the American dumping ground, would be used to murder the president.

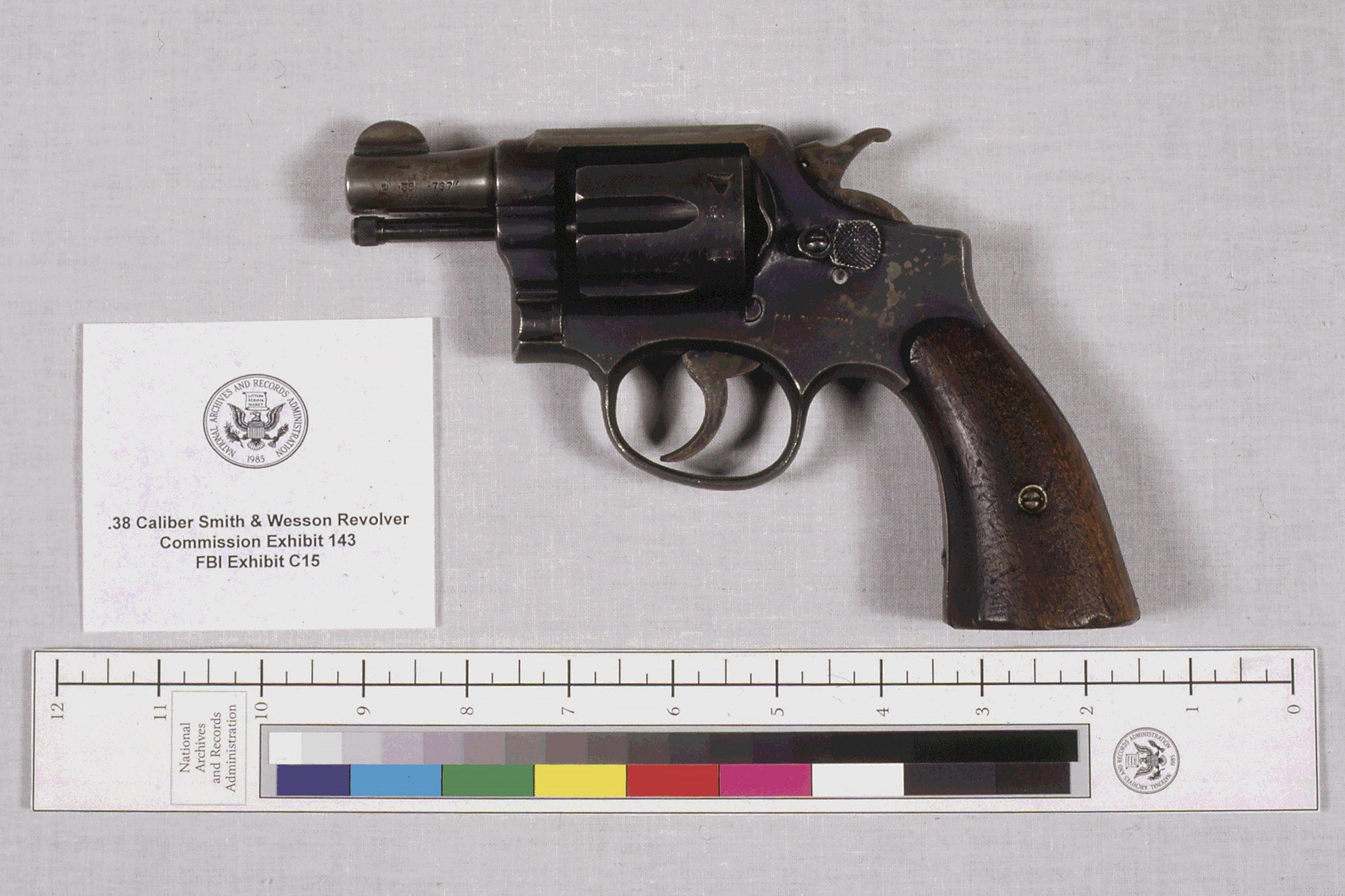

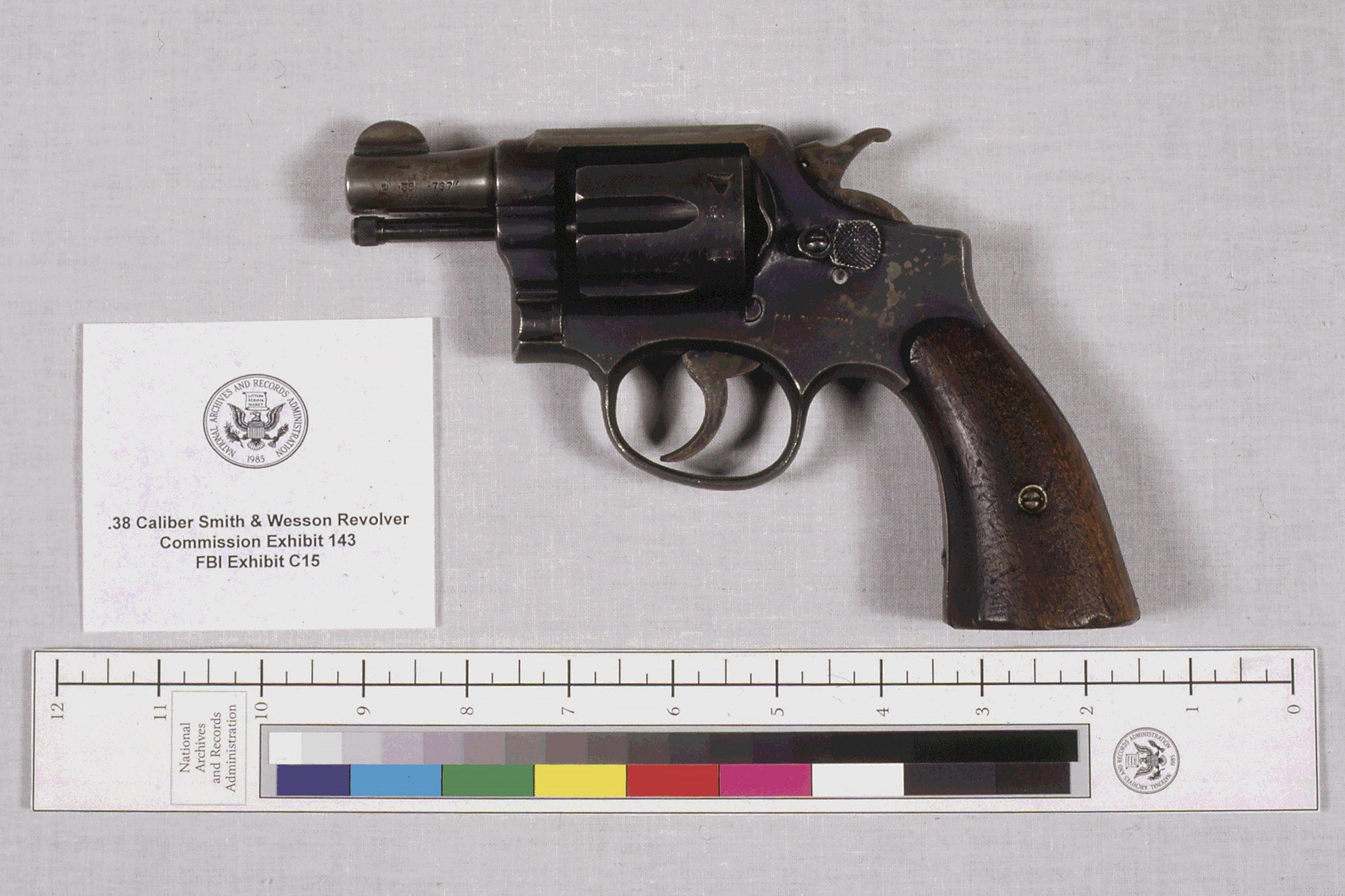

National Archives and Records Administration

It wasn’t the only gun Oswald bought through the mail and used on Nov. 22, 1963. An hour after killing Kennedy and fleeing the scene, Oswald shot and killed Dallas police officer J.D. Tippit using a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson handgun he had also purchased pseudonymously through the mail. That weapon, too, was a war surplus import—shipped to Europe and then reimported for sale on the world’s biggest gun-consumer market. Like Klein’s, Seaport Traders, a Los Angeles-based importer and mail-order retailer, received an order form and a money order and shipped the gun off to “A. Hidell,” but not before sawing down its barrel to 2 inches for increased concealability.

While Oswald’s Carcano lives in infamy, his handgun arguably better represented the social changes to come in the years to follow. The 1960s would be the decade of the handgun. From 1962 to 1968, handgun sales in the United States increased 400 percent, driven by fears of reported rising crime rates and Black urban rebellions. By 1968, when the Gun Control Act would attempt to slam the door on the flood from overseas, half of all handgun sales were imports, and those guns—whether they were war surplus like Oswald’s or cheaply manufactured in postwar Western Europe—were across the board less expensive than new U.S.–made handguns, driving down prices and forcing U.S. gunmakers to be competitive. Then as now, a handgun was used in more than three-quarters of all gun deaths.

In Oswald’s two guns we see the emergence of the United States as not just a gun country—it surely already was—but as the gun country it would become in the second half of the 20th century, one built not on tradition or abstract rights but on abundance, on a consumer market flooded with cheap firearms, the world’s bounty brought to American shores. That bounty enabled the murder of a president and the arming of a population increasingly anxious about crime and social uprisings. Today’s gun culture remains a reflection of that moment, grounded in both fear and plenty.